Billboard Architecture

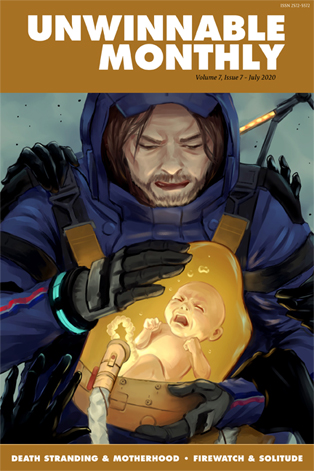

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #129. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #129. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Architecture and games…

———

The structures in Yakuza 0 are pretty bare bones on the whole. Stroll through the streets of Sotenbori or Kamurocho and you’ll see a bunch of buildings that are just big boxes. This wasn’t the result of some technical problem or limitation, though. The developer behind the game, Sega, made them like this on purpose. The reason isn’t very hard to figure out. There must be thousands of similar structures in Osaka and Tokyo. These two cities were the sources of inspiration for Sotenbori and Kamurocho.

Sotenbori and Kamurocho are filled with bright lights and flashy colors. These are however only found on the signage. Take some time to explore Sotenbori or Kamurocho and you’ll soon realize that most of the buildings in them are pretty plain. They have the same open floorplan. They have the same number of stories. They have the same lack of doors and windows. Most of them are even made from what are clearly meant to be the same construction materials. Why are Sotenbori and Kamurocho filled with such bare bones buildings? What you’re seeing is the product of a particular series of historical circumstances that came to be known as kanbankenchiku. This literally means “billboard architecture,” but you’ll almost always find it untranslated. The term pretty much says it all. These are buildings that only stand out from the surrounding streetscape on account of their signage.

What exactly is kanbankenchiku and why is it worth knowing about? Let’s dive into the details of kanbankenchiku and then we’ll take a look at what Sega has to say about this particular form of architecture.

The origins of kanbankenchiku are found in the Meiji period. This was the point in time when people started looking to Europe and America for sources of inspiration. In terms of architecture, some of the changes were purely technical, but others were mostly a matter of style. The shops known as machiya for example were almost completely made from wood in the Keio period. They consisted of pillars and beams which supported lattices named koshi that were styled in such a way as to indicate the type of services offered inside them. They had deep eaves called noki. These buildings tended to be rectangular in shape. The main entrance was located on the smallest side. They had been using them for hundreds of years, but the Meiji period was all about modernization, so people replaced machiya with a sort of structure called a seiyokan. Similar to machiya, these tended to be rectangular in shape. The main entrance was located on the largest side, though. These buildings also had basically no eaves. While some of them were covered with sheets of copper to make them resistant to fire, seiyokan were almost always made from brick as opposed to wood. Signage indicated the type of services offered inside them. They were often decorated with elaborate masonry, so these buildings weren’t exactly bare bones, but seiyokan were definitely an early form of kanbankenchiku. The structures kind of set the stage for what came next. I unfortunately don’t remember seeing a seiyokan in Sotenbori or Kamurocho.

They were definitely resistant to fire, but seiyokan proved susceptible to earthquakes. This was mostly on account of their construction materials. Thousands of seiyokan came tumbling down after Tokyo was shaken by a particularly powerful earthquake in the Taisho period. This came to be known as the Great Kanto Earthquake. These buildings were replaced by a kind of kanbankenchiku called a barakusu. In terms of their form, barakusu were very similar to seiyokan. They tended to be rectangular in shape. The main entrance was located on the largest side. They had basically no eaves. Tokyo was reduced to ruins after the Great Kanto Earthquake, so people cut a lot of corners when it came to construction, though. The largest buildings looked like warehouses, but most barakusu were just rickety shacks. In terms of their construction materials, people used almost anything which they could find, so these buildings were often made from sheets of iron. Wood was pretty common, too. They had only a couple of doors and windows. They weren’t designed by an architect, so barakusu tended to be structurally unsound. This means that barakusu hardly ever had more than a second story. Since these were simple structures, they tended to have open floorplans. They barely stood out from the surrounding streetscape, so barakusu were of course covered with all sorts of signage. Spend enough time in Sotenbori or Kamurocho and you’ll come across a lot of barakusu. The best examples of them are in Champion.

Some of them were torn down, but a lot of barakusu were still standing in the Showa period. Many of them didn’t make it past the Second World War, though. Tokyo in particular became a target. Osaka was bombed several times, too. The result was that most of the barakusu in these two cities were reduced to ruins. People replaced them with another kind of kanbankenchiku called a nagaya. These were very similar to barakusu at first, but after the Economic Miracle, they were often made from slabs of concrete as opposed to sheets of iron or wood. Renovations were also common. They had become huge cities by this point in time, so property values in Osaka and Tokyo had risen to record levels. Since the structures made from sheets of iron or wood started showing signs of age, many of them were converted to concrete. This made them a lot more structurally sound, so people were able to increase the number of stories. This gave nagaya some added space for people to plaster with signage. Take a walk around Sotenbori or Kamurocho and you’ll come across these buildings around almost every corner. While some of them are made from sheets of iron or wood, most of these bare bones buildings consist of nothing but concrete. They have a lot of bright lights and flashy colors. In other words, they’re pretty hard to miss. You’ll find some good examples of them if you take a stroll through the Kamuro Shopping Area.

The streets of Sotenbori and Kamurocho are filled with kanbankenchiku. What exactly does Sega have to say about this form of architecture, though? When you compare Yakuza 0 and Yakuza Kiwami 2, the answer becomes pretty clear.

You can see some signs of construction in Yakuza 0, but Sotenbori and Kamurocho are clearly changing shape in Yakuza Kiwami 2. Most of the kanbankenchiku are being replaced by structures made from steel or glass like the Millennium Tower. The main difference would definitely be the lack of signage. Since they weren’t designed by architects, kanbankenchiku like barakusu and nagaya came to be almost completely covered with signage. There was no planning behind this process. People just did whatever they wanted. This means that streetscapes in Osaka and Tokyo became reflections of the people who created them. In other words, they became symbols of democracy. You can see this being turned upside down by structures like the Millennium Tower in Yakuza Kiwami 2. In my opinion, what Sega has to say about kanbankenchiku is that all of the bright lights and flashy colors in Sotenbori and Kamurocho might be more meaningful than first meets the eye. The same could be said about Osaka and Tokyo.

———

Justin Reeve is an archaeologist specializing in architecture, urbanism and spatial theory, but he can frequently be found writing about videogames, too. You can follow him on Twitter @JustinAndyReeve.