Necrobarista is Haunting, Innovative and Begging for Interpretation

I.

(No spoilers)

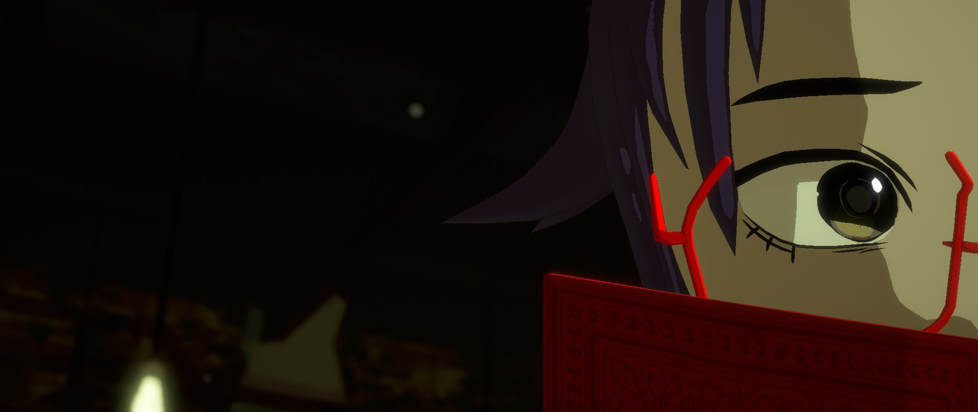

Route 59’s Necrobarista has a lo-fi aesthetic, but it’s utterly, uniquely gorgeous.

The art to this game’s visuals is really in the rigging and posing of its characters — it lives and dies by the careful positioning and framing of their bodies, and by the personalities contained within. Even in a succession of relatively static frames, Necrobarista shows the emotion and loveliness and persisting ambiguity that light, expression and mise en scène get across when they’re given space to breathe. Its visual storytelling is careful, filmlike in language, but still a game in terms of feel.

And in this way, Necrobarista pulls off a rare kind of nuance. It shows violence, but its violence has no physicality. It’s intimate, but no single character represents the player’s vantage.

Instead, we see everyone through everybody else’s eyes. We’re shown the distinct facets of each character in many contexts, and from several perspectives, but we see definite identity only in fragments. Because of this, the characters feel whole in a way unfamiliar to most games. Not one of them is me, but each reads as an entire, distinct other — lovable but half-obscured, understandable but indefinable — living half in text and half in implication.

In film and literature, this type of storytelling is common. In a game, it’s practically a contradiction in terms.

II.

(Minor spoilers)

I’m reminded of Edwin Evans-Thirwell’s essay “Towards a Carrier Bag Theory of Videogames,” where he applies Ursula Le Guin’s theory of fiction to narrative design. Rather than linear narratives, where (per Leguin) “the arrow or spear, starting here and going straight there and THOK! hitting its mark (which drops dead).”

“To present heroes and their deeds as an originary myth,” Thirwell goes on, “is to impose this narrow fatalism on all of history — always traveling via conflict, always ending with a kill.” Instead, “Leguin proposes the story as ‘carrier bag,’ gathering its elements into ‘a particular, powerful relation to one another without bullying them into order or using them as a backdrop.”

Thirwell’s example of carrier bag narrative design is Pathologic 2, where the player is only one of three protagonists, they can die easily and time doesn’t wait for them. That said, I’d argue that Necrobarista is an even more perfect take on this style of fiction — while Pathologic 2 is, at its core, a survival game, the actual game of Necrobarista is itself a carrier bag narrative. In a very real sense, Necrobarista has no verbs beyond the association of its disparate parts. In dialogue, a word will sometimes be highlighted in yellow, and at the end of each chapter, every highlighted word hovers in a cloud. We’re prompted to choose seven of them, and we’re given their associations, accompanied by a rush of static.

Blood (MAGIC)

Collingwood (MELBOURNE)

Sadist (MADDY)

Bittersweet (DEATH)

These associations might be glimpses into the underlying nature of things, or they could just be another flawed tool of interpretation, subject to the bias of whoever was speaking at the time. As is common in Necrobarista, their concrete meanings are never laid out. In introducing this mechanic, the game itself can only remind us of our own role in engaging with its story:

“What will be precious to you?”

“What will you choose to carry with you?”

III.

(No spoilers)

I love Necrobarista mainly because it uses its carrier-bag-ness and its filmlike nuance to tell a fixed narrative that goes nowhere.

From a narrative design perspective, the game is entirely linear. It’s engaging, and it’s profoundly involving, but it doesn’t do this by becoming a mass of branching choices. No part of the text is about that type of narrative maximalism, and the mechanics echo this: by gamifying the interpretation of its story, Necrobarista allows itself to be winding, poetic and meticulous, without becoming alienating or overwhelming. Instead of making you an agent in its story, it only asks you to take what you need from it.