The Goth Revival

This is a reprint of a feature story from Issue #22 of Exploits, our collaborative cultural diary in magazine form. If you like what you see, buy it now for $2, or subscribe to never miss an issue (note: Exploits is always free for subscribers of Unwinnable Monthly).

This is a reprint of a feature story from Issue #22 of Exploits, our collaborative cultural diary in magazine form. If you like what you see, buy it now for $2, or subscribe to never miss an issue (note: Exploits is always free for subscribers of Unwinnable Monthly).

———

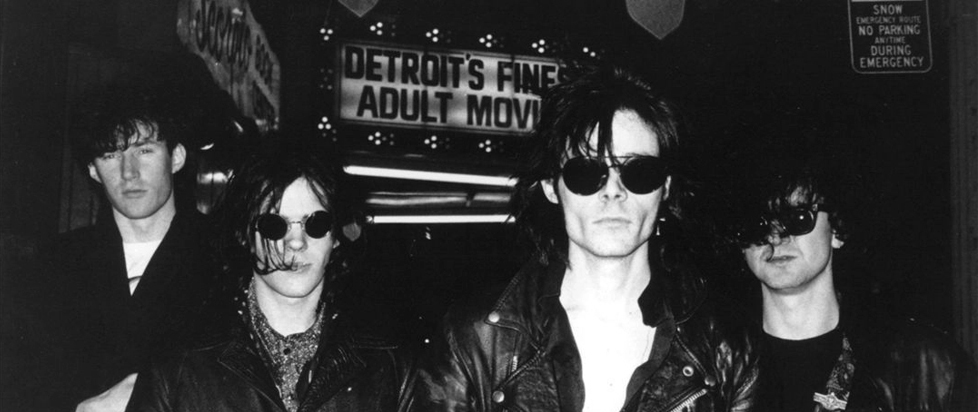

Talking about genre in music is often a ridiculous exercise of carving smaller and smaller niches of sub-sub-subgenres to precisely describe the one band that fits in that specific pigeonhole. Such arguments often draw from a dizzying array of criteria – sound, arrangement, geography, history, style (both musical and sartorial), nebulous terms like “heavy” and the capricious whims of tribal music scenes, to name but a few – to the point that it all winds up being a taxonomy of meaninglessness. This probably goes doubly for goth.

There seems to be a general consensus that goth rock came out of post-punk (itself less a term for a specific genre or sound than it is a historical period of musical experimentation, ranging roughly from 1978 to 1984) and was typified by specific albums by Siouxsie and the Banshees and The Cure, though plenty of folks will argue that earlier acts like The Doors, Velvet Underground, Joy Division and The Damned were all goth bands too. This is the sort of thing that happens in conversations like this, which I think is the best evidence that music is a slipstream and genre is bunk.

Still, goth is a thing. I know it when I hear it (though in a post-emo world, no longer when I see it). There is no real unifying sound or subject matter, though jangly guitars, a danceable beat, anxious vocals and dark, decadent romanticism are common. Mostly I see goth for what it is: an adjective, to apply to anything in a certain mode that catches my fancy. Are Nine Inch Nails and Portishead and Wovenhand goth? Sure, why not. Andrew Eldritch can say his band Sisters of Mercy isn’t goth till the end of days and he’ll always be wrong.

Still, goth is a thing. I know it when I hear it (though in a post-emo world, no longer when I see it). There is no real unifying sound or subject matter, though jangly guitars, a danceable beat, anxious vocals and dark, decadent romanticism are common. Mostly I see goth for what it is: an adjective, to apply to anything in a certain mode that catches my fancy. Are Nine Inch Nails and Portishead and Wovenhand goth? Sure, why not. Andrew Eldritch can say his band Sisters of Mercy isn’t goth till the end of days and he’ll always be wrong.

In the 90s, driven by the popularity of industrial music, Anne Rice novels and Vampire: The Masquerade, goth cross-pollinated with countless styles, spawning endless, mostly European acts. In the mid-2000s, though, it suddenly vanished, ironically overtaken, it seemed, by the post-punk revival (think Interpol, which managed to channel a lot of goth’s sonic vibes without ever actually feeling particularly goth).

Then all of a sudden, in the last ten years, there’s a new, albeit quiet, goth renaissance happening. While looking for something new to listen to instead of putting on Floodland for the millionth time, I discovered that I suddenly had hundreds of acts to pick from. Now, granted, I am casting a wide net here: If I can imagine it playing at the Batcave or the Pyramid Club circa 2001, I am comfortable calling it goth. Both those places played the Smiths pretty frequently, so your mileage may vary.

There are two basic flavors of this revival to my ear. The first is firmly a return to the old ways, excavating the original goth sounds (and some general post-punk and 80s ones as well) to bring forth songs that sound both new and somehow familiar. There is a clear string of DNA leading from Christian Death to Beastmilk (and the subsequent band Grave Pleasures)(yea, yea, they’re deathrock and not goth but whatever). Squatter goths Belgrado evoke Skeleton Family, Makthaverskan channels Siouxsie. Terminal Gods obviously have some Sisters of Mercy records on their shelf. HAVAH and Rope Sect seem to spring from the same place as Red Lorry Yellow Lorry. Lebanon Hanover’s “The Moor” sounds like a lost track from the Lost Boys soundtrack.

There are two basic flavors of this revival to my ear. The first is firmly a return to the old ways, excavating the original goth sounds (and some general post-punk and 80s ones as well) to bring forth songs that sound both new and somehow familiar. There is a clear string of DNA leading from Christian Death to Beastmilk (and the subsequent band Grave Pleasures)(yea, yea, they’re deathrock and not goth but whatever). Squatter goths Belgrado evoke Skeleton Family, Makthaverskan channels Siouxsie. Terminal Gods obviously have some Sisters of Mercy records on their shelf. HAVAH and Rope Sect seem to spring from the same place as Red Lorry Yellow Lorry. Lebanon Hanover’s “The Moor” sounds like a lost track from the Lost Boys soundtrack.

The other strain is perhaps rooted in the cultural melting pot of the present day, drawing less from specific goth bands and more from the broad tapestry of nostalgia for the 80s that suffuses the late 2010s. A lot of it owes something to retrofuturist sounds of synthwave, which often feels rather goth in its own right (Slasher Film Festival Strategy, Pentagram Home Video and Julian Winding all come to mind).

Cabaret Nocturne darkens those Hotline Miami vibes. Drab Majesty draws from a broad range of 80s influences and refines them down to a gothy essence and She Past Away does something similar with the darkwave sounds of the early 2000s. Boy Harsher’s “Pain” could easily be subbed in to the blood rave scene in the first Blade film. The lyric “I feel guilty being alive when so many beautiful people have died,” from Cold Cave’s “Confetti,” is about as goth as you can get.

And I don’t even have room to get into unique outliers like Chelsea Wolfe, Zola Jesus and Lana Del Rey (surely you knew beach goth is a thing).

There isn’t a unifying goth sound, no, but the goth revival crystallizes a unifying feeling. It isn’t just dark, or romantic, or straight mopey. Its a kind of anxious resignation in the face of a mutable, existential dread born of a precarious world that doesn’t seem to have changed for the better in 40 years; when the end of that world is nigh, goths will make the music to dance to.

———

Listen to the companion playlist.