A Beautiful Pattern: Knives Out and What’s Wrong with America

“I keep waiting for the big reveal.”

Before the preview screening of Knives Out, writer/director Rian Johnson came on screen and asked that we not reveal “whodunit.” So I won’t be doing that here. But Knives Out is a movie of many-layered twists and turns – of donuts within donuts, as our intrepid “gentleman sleuth” would have it – and it will be impossible to discuss it in any meaningful way without getting into at least some of the film’s many revelations.

Which is another way of saying that there will be spoilers from here on out, though I’ll keep them as mild as I can.

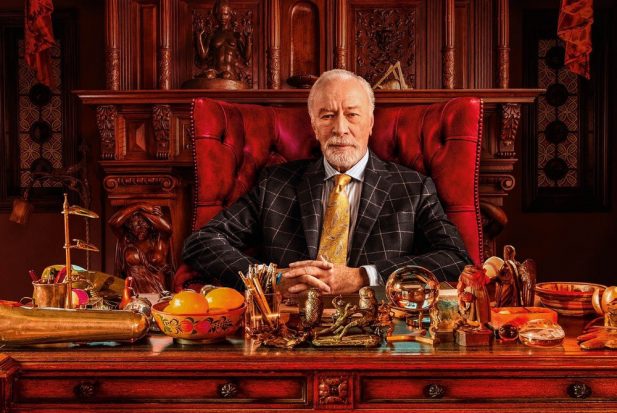

First off, Knives Out is really two movies – maybe more. On the surface, it is a mannered whodunit in the grand spirit of Agatha Christie, with Daniel Craig’s delightfully absurd Benoit Blanc standing in for Hercule Poirot or whichever other famous sleuth you’d like. In case the film’s influences aren’t obvious enough, there’s a scene where characters are watching Murder, She Wrote.

The longer the film simmers, however, and the more of the mystery that gradually boils away, the more we are left with the other movie; the one that is a sharp stick in the eye, not only of the 1%, but of everyone on a certain side of a political line – and many of the people who claim to be on the other side, as well.

It’s a lot of weight to put on the shoulders of a simple, charming murder mystery of the old school to say that it exposes the rot at the heart of American exceptionalism and the fragility and hypocrisy of white neoliberal allyship; but it’s also impossible to watch the movie and deny that those are precisely the targets upon which it has set its sights.

Knives Out isn’t coy about it, either. I don’t think it ever uses Trump’s name, but it may as well. One character is called a “literal Nazi” and an “alt-right troll,” while others are called “SJWs” and “snowflakes.” Red caps are mentioned.

But those are just the surface of a many-layered critique of so much that’s wrong with a certain strain of thinking in this country. The “self-made” rich; those who claim to have pulled themselves up by their bootstraps. Those who want to hang on to what is “ancestrally” theirs, even when that ancestry runs very shallow indeed.

The people who were hitting Rian Johnson with death threats on Twitter over making The Last Jedi “too political” are going to love this one, is what I’m saying. (That’s a joke. They won’t even bother watching it, because it isn’t about laser swords.)

Since I am writing this for Unwinnable, I feel like I can make certain assumptions about my audience. Namely, that whoever is reading this probably agrees that immigration is good, actually, that concentrating a larger and larger amount of wealth among a smaller and smaller portion of the (mostly white) population is bad, and so on.

For those of you who are in that camp, there is a shot at the end of Knives Out that is the stand up and cheer moment of 2019 cinema – a year that has had lots of movies delivering variations on this same very timely and necessary message.

At the end of the day, that shot also drives something else home: that these messages, more than the mystery of whodunit and how and why, are what Rian Johnson really wants to be doing with this movie. And if the internet trolls want to insist that he’s doing so simply to earn brownie points with the SJW crowd, well, he picked an awfully expensive and star-studded way to do it.

Before making The Last Jedi, Johnson’s filmography was exclusively noir retreads. From his brilliant debut Brick to the time-travel noir Looper to episodes of Terriers and Breaking Bad to his best film, prior to this one, The Brothers Bloom, which, for whatever reason, even the marketing of Knives Out seems to have forgotten, never mind that it has more in common with this picture than anything else he’s ever made.

I’ve enjoyed everything that Johnson has done, even though his early filmography also reveals some gaping holes in his arsenal of talents; notably, his deployment of women, which I’m happy to say has improved considerably in recent years. It’s nice to see a director absorb apt criticism and adjust his oeuvre accordingly.

As a fan of old dark house movies and anything where a bunch of colorful suspects all gather in a big, creaky house for the reading of a will, it’s also nice to see a director take the cache afforded him by having helmed a Star Wars flick and convert it to a passion project that’s essentially Agatha Christie fanfic. For him to do so in the service of such an undiluted political message is icing on the proverbial cake.

All those politics would only work if the movie also worked, which luckily it does. Knives Out may be somewhat short on atmosphere, but Johnson has a good handle on how to direct and misdirect. This is a film that tells you everything, and then tells you again, but keeps you looking the other way.

Its wheels-within-wheels reminded me almost as much of Richard Matheson’s great magician whodunit Now You See It as the books and films it is more consciously aping. (I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that Johnson was a fan, especially given the magician paraphernalia littered around the film’s expansive house.)

On its own, however, the whodunit plot would ultimately feel slight – as so many do, upon their final resolution. Just another in a long line of cozy murder mysteries in big, shadowy houses full of family secrets. It’s that second movie – the one about America and immigration, about politics and money, about sincerity and hypocrisy – that gives the first movie substance to help it last beyond the two hours and ten minutes you’ll spend unraveling its delightful web.