Undoing Ruin

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #117. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #117. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Adam examines the reasons why he and the pop culture consensus differ in opinion.

———

Environmental themes appear consistently throughout director Hayao Miyazaki’s work, perhaps most famously in 1997’s Princess Mononoke. 13 years earlier, though, Miyazaki released his second feature-length film, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, which offers something like a template for his later explorations of the relationship between society and nature. In Nausicaä, Miyazaki introduces some of the ideas that seem most urgent in his work: the reality of rampant environmental degradation paired with a steadfast belief in the possibility of better, more just futures.

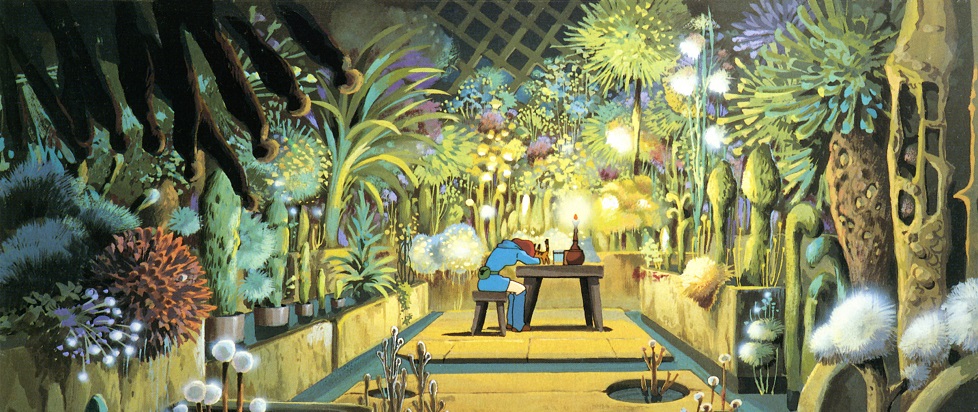

Nausicaä takes place in a world still reeling from the effects of a war that ended a thousand years ago. That war’s pollution and environmental impacts persist in the form of the Sea of Decay, a toxic jungle inhabited by massive bug-like creatures called Ohms that encroach on the humans’ surviving settlements, including the Valley of the Wind, where protagonist Nausicaä lives. In this bleak setting, the Pejite and Tolmekian nations war with each other while also trying to eradicate the Sea of Decay, even if it means using the same technologies that poisoned the world centuries ago. Nausicaä instead hopes to chart a different path, seeking to understand the Sea of Decay rather than destroy it. In the process, she discovers evidence of a vibrant, non-toxic world that the major powers have missed, and she intends to protect it.

Nausicaä can be read as a kind of thematic and narrative precursor to Mononoke, employing similar plot beats and general story structure to explore similar ideas. Among other traits held in common, both films feature warring human factions that also target and destroy the natural world in the course of their conquests, triggering violent responses from the representatives of that world (the Ohms in Nausicaä, the gods of nature in Mononoke). And both feature protagonists (Nausicaä and San) that reject the claims of human superiority made by the combatants and instead empathize with nonhuman life in hopes of fostering a better world for all in it. In some respects, the two films act as retellings of the same story, each offering something unique in the details it foregrounds.

Like Mononoke, Nausicaä holds out hope that the schisms opened between nature and society might be mended. One moment in Nausicaä stands as a potent warning, though – a representation of the horror and hubris of human antagonism toward the planet.

In the film’s finale, an enormous army of Ohms stampedes toward the Valley of the Wind, baited by Pejite soldiers hoping to use the Ohms against the Tolmekians. Facing imminent obliteration, the Tolmekians resurrect an ancient bioweapon, the Giant Warrior, which fires off enormous bursts of lasers from its mouth that incinerate huge swathes of the Ohms.

It’s a chilling image, a grim illustration of the incredible destructive power humans can wield. It’s also fleeting. The Warrior doesn’t last long before it collapses in on itself thanks to the Tolmekians having rushed it to the frontlines in an unstable, unready form. Its powers seem unthinkable, but it barely makes a dent in the insect onslaught before evaporating. In this light, the Warrior’s arrival takes on an almost pitiful quality. Even in humanity’s most vicious attempts to dominate nature, Miyazaki sees an inevitable failure. As in Mononoke, we can’t even get the destruction of our own planet right.

Neither Nausicaä nor Mononoke depicts a binary contrast between humans and nature, however. The two are not just opposing sides of some conflict but instead deeply embedded within each other. In these films, the central crisis doesn’t develop because nature must necessarily lash out at humanity, or because humanity is destined to extinguish its own habitat. Instead, the problems arise due to a belligerent faction of humanity misunderstanding (perhaps intentionally) its relationship to the world it inhabits. The violence of the natural world results from these humans’ exploitation of that relationship. Nausicaä and San as characters both embody a richer, more reciprocal connection between society and nature, and it’s in that connection that Miyazaki finds hope for the future.

Nausicaä ultimately helps prevent both the decimation of the Valley and the slaughter of the Ohms through her own sacrifice, and the Ohms revive her, making tangible the bond she had hoped to establish. As the film concludes, it offers a few images of a budding future in which the natural world and the remaining humans live harmoniously.

Released in 1984, Nausicaä’s themes have grown more vital as the effects of climate change manifest more vividly each year. Miyazaki’s outlook here is not hopeless, though he does not ignore the significant obstacles in our path. If there is to be a future worth living in, Miyazaki seems to believe it will not be created through efforts to command and control the climate through more sophisticated technologies; these would perpetuate a long and futile history of industrial societies’ attempts to dominate nature. These attempts may at times grant these societies temporary advantages, but in the long-term, endeavoring to bend nature entirely to humanity’s will always lead to catastrophe.

While this appears to be the current trajectory for our efforts to deal with the climate crisis, with geoengineering efforts on the horizon despite risks still barely understood, in Nausicaä Miyazaki rejects defeatism. The world of the film renews itself, even after a thousand years of apocalypse. In this, as in Mononoke and elsewhere, the director sees potential for healing and restoration even after natural devastation that seems absolute. But making something of that potential requires a radical paradigm shift.

———

Adam Boffa is a writer and musician from New Jersey.