Microaggressions

Being a queer gamer is fraught with compromises. Given that we’re still marginalized, we constantly bump up against content that is actively hostile to us, intentional or not. Homophobic design is just par for the course, though, when you think about the homophobia that still infests the gamer consciousness. One only has to turn on voice chat in a multiplayer game to bear witness to this. Yet even when we unplug, old biases and prejudice leak into single player content – not everything, mind, as most games are simply content to pretend we don’t exist. But when the games we love don’t love us back, how do we handle that? Where’s the line in the sand where we say this is unacceptable? The answer, unsurprisingly, isn’t simple.

Most homophobic design takes the form of microaggressions, which are basically brief – almost in passing – attacks on us that nevertheless seek to shape us out of people’s realities. It could be something like a tossed off comment about how surprised someone is that a gay man could lift a heavy box. It relies on stereotypes but treats them as a factual part of the reality to the point where very little thought or effort goes into it. It just seeks to be the way things are. Of course gay men are all femme and weak, these microaggressions posit without actually going on the active offensive. Instead, they act like their version of reality already won.

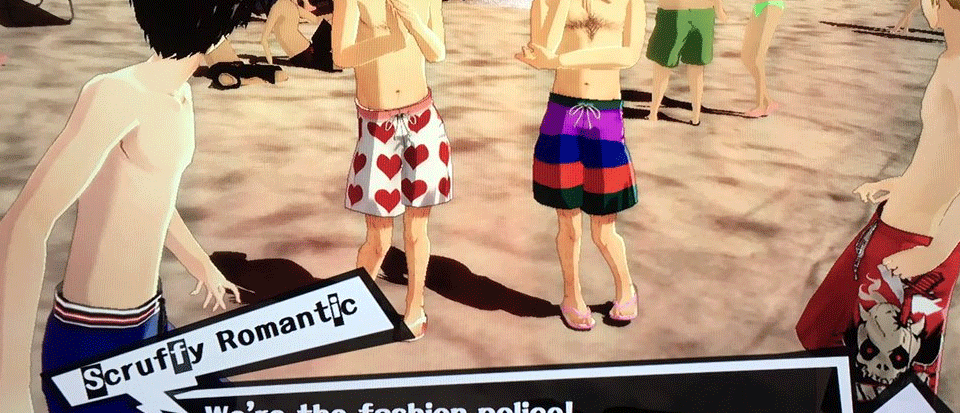

One example of microaggressions creating a hostile reality for queer peeps is a couple of moments in Persona 5, when two men, dubbed Beefy Trendsetter and Scruffy Romantic, walk up to one of your male party members, Ryuji, and hits on him, making him visibly uncomfortable. It’s a throwaway gag that’s meant to illustrate how dangerous and illicit the red light district of Shinjuku is by playing up the trope that gay men are predators. But it’s the throwaway nature of it that makes it a microaggression and makes it hurt. It establishes a bigoted trope as if it’s just assumed to be correct, warping the game’s reality to one where the trope solidifies as fact to everyone but its subjects. The casualness just makes it all the more scathing.

Sometimes the microaggressions blow up into thoughtless erasure, as is the case with Assassin’s Creed Odyssey’s DLC. In the base game, you can play your character as if they were any sexuality, which was touted as a win for diversity in games. But in the DLC, your character will have storyline hooked up with the opposite sex to birth a child. In a game where choosing your sexuality was touted as a big feature of the game, reversing that was a thoughtless slap in the face to an entire community. It also normalized and recentered heterosexual relationships as the default, a position that’s all to common in media, but especially hurts when the commitment to accommodating queer people is proven to merely be lip service.

Microaggressions, when taken collectively, begin to wear on your soul. And yet I continue to play games that have them. For all its faults, I enjoyed Persona 5. The homophobic bits are a drop in the bucket compared to the rest of the content in the game, but that’s not the reason I endure the indignities. It’s because microaggressions have become so ingrained in my life as a queer person that I just accept them as a reality of existing. I don’t bat an eyelash at the Beefy Trendsetters of the world because I’m so used to dealing with them at this point. Right or wrong, that’s how I survive in the world, because the alternative is letting their reality rule my own, and I refuse to give them that power.

Does that mean that I don’t have a red line I won’t cross when it comes to offensive content in a game? Of course not. If a game’s homophobic content is so prevalent that it defines the experience and poisons the whole thing, then of course I’m going to put it down, or not play it if I hear about it. I think it’s important to send a message in some cases that it’s not okay. That Assassin’s Creed DLC is something I will absolutely not be getting, for one. And I think it’s even more important to send a message as an ally, as well, to avoid certain media that harms fellow marginalized people. The new version of Catherine, which was already rife with transphobia, leans even harder into it by adding a new ending that detransitions the trans woman and portrays it as a “good” ending. And let’s not forget how Detroit: Become Human colonizes the Black struggle for liberation from white supremacy and transplants it onto androids, going so far as to insert lines from Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s I Have A Dream speech into one for android rights. Avoiding games is definitely an option that’s on the table and should especially be on your mind if you hope to be a good ally.

But it’s still complicated when it comes to consuming media while queer. Most that you come across is compromised in some way, upholding the heteronormative default while taking pot shots at anyone who doesn’t fit that mold. At a certain point, if you want to consume any amount of media, especially if you’re a critic like me, you’ll eventually come across some problematic pieces that will make you question the motives of the developers. And you’ll question if you’re still a good person because you’re enjoying a problematic piece of media that takes aim at you. Thankfully, the answer is that the media you consume doesn’t have to define you, that you can enjoy problematic media without losing your soul, and that you can have a sense of morality that says when enough is enough.