Fire, Loss and the Works of Hands

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #116. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #116. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Revisiting stories, old and new.

———

On April 15, 2019, the roof of the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris caught fire. Within hours, the roof and spire were destroyed. There are, as of the time of this writing, no concrete plans to rebuild the roof, and experts estimate that the work, once started, could take twenty to forty years to complete.

There is a story I want to tell, but first there is another story I have to tell, and one more after that.

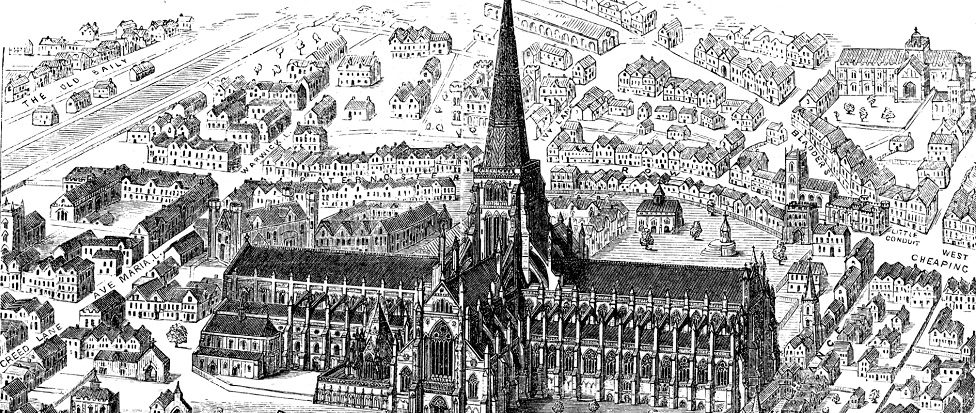

On June 4, 1561, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, the spire of Old St. Paul’s Cathedral in London was struck by lightning and burned. At 489 feet, the Spire at St. Paul’s was the tallest in Europe except for Lincoln Cathedral (itself the first building to pass the Great Pyramid as the tallest building in the world). Having been built between 1087 and 1240 (with the spire added by 1314), the cathedral was already in decline at the time of the fire, and the spire was never rebuilt.

It is nearly a truism that cathedrals burn. In their history, many medieval gothic structures are not so much maintained as built and rebuilt. And, frequently, eventually not rebuilt.

It is difficult to imagine that Notre Dame will not be repaired, but then Old St. Paul’s stood without a spire for 105 years.

In the one hundred and fifth year, on September 2, 1666, London burned. Old St. Paul’s, having been partially restored by Inigo Jones and under consideration for further work by Christopher Wren, was destroyed entirely.

Construction of the current St. Paul’s Cathedral, designed by Wren, commenced in 1675, and was declared complete in 1711. The dome of St. Paul’s has become an icon, and survived two direct hits to the cathedral by German bombs during the Battle of Britain in World War II.

This dome, of course, would never have existed had Old St. Paul’s not burned, and given Wren’s opinion of the condition of the old cathedral in the 1660s, it seems reasonable to speculate that whatever portion of it might have survived to the 20th century would not have held up so well to aerial assault as the new building did.

It is difficult, in these circumstances, to consider entirely what is fortunate and what is a loss. I have visited both St. Paul’s and Notre Dame, twenty years ago in what feels increasingly like another lifetime. I climbed 528 stone steps to the galleries of St. Paul’s and looked both out over the city of London and down through a porthole to the floor of the cathedral 85 meters below. It was an occasionally claustrophobic experience, but one never knows if one will have the opportunity or strength to do so again. I have walked past Notre Dame illuminated at night, a beacon as I crossed the Seine so late at night that I wondered whether my journey was entirely safe and reasonable. I do not remember if I ever entered the building, which is perhaps a bit out of character, but then I nearly became a smoker on that trip, which was entirely out of character.

My children have never been to Paris. If and when they go, the Notre Dame they see will be different than the one I saw.

It is possible to revisit that cathedral as a digital artifact in the 2014 videogame Assassin’s Creed Unity, but there are a number of ironies involved, beyond, of course, the attempt to perform a sort of pilgrimage in the guise of a virtual mass murderer. The spire that burned this year, and which is preserved, in a way, in Assassin’s Creed, was built in 1859 after Victor Hugo’s novel The Hunchback of Notre Dame inspired a series of massive renovations to the then-decrepit structure. During the period in which the game is set, however, the 1780s and 90s, Notre Dame’s original 13th-century spire had partially collapsed and was in the process of being removed. For more than fifty years, Notre-Dame de Paris had no spire at all.

It has been said that history does not repeat, but it rhymes.

I turned on CNN on April 15, which is entirely out of character for me, in order to see the fire. Every loss is a loss, even if every loss is not the same kind of loss. The fine thing about stories invested in objects is that the object can never be entirely encompassed by the story. When we see and touch them, that experience is enriched by the stories we hear and re-tell, but part of the object exceeds and escapes those stories. This is part of what makes their loss so irreparable. I can never walk through Old St. Paul’s. I can never see Notre Dame quite as it was, even if I know that part of what it was had already been lost when I was there, and both that loss and this loss are both part of the story of that object. Part of the loss of an object shaped by human hands is the loss of the connection to those hands, and stories, whatever they are, are not primarily things shaped by hands.

Cathedrals burn. Loss is an inherent property of objects. Mitigating that loss is one of the purposes of stories. It is an impossible project. It is good to remember and mourn in that remembering. It is good to rebuild, and in this instance it is good that the rebuilding will take time. Cathedrals are the project of generations, and we now touch those generations in their loss, their hope and the work that we share with them.

———

Gavin Craig is a writer and critic who lives outside of Washington, D.C.