Man Against Time: The Big Clock on Blu-ray

“Just 36 hours ago I was a decent, respectable, law-abiding citizen with a wife and a kid and a big job.” – The Big Clock (1948)

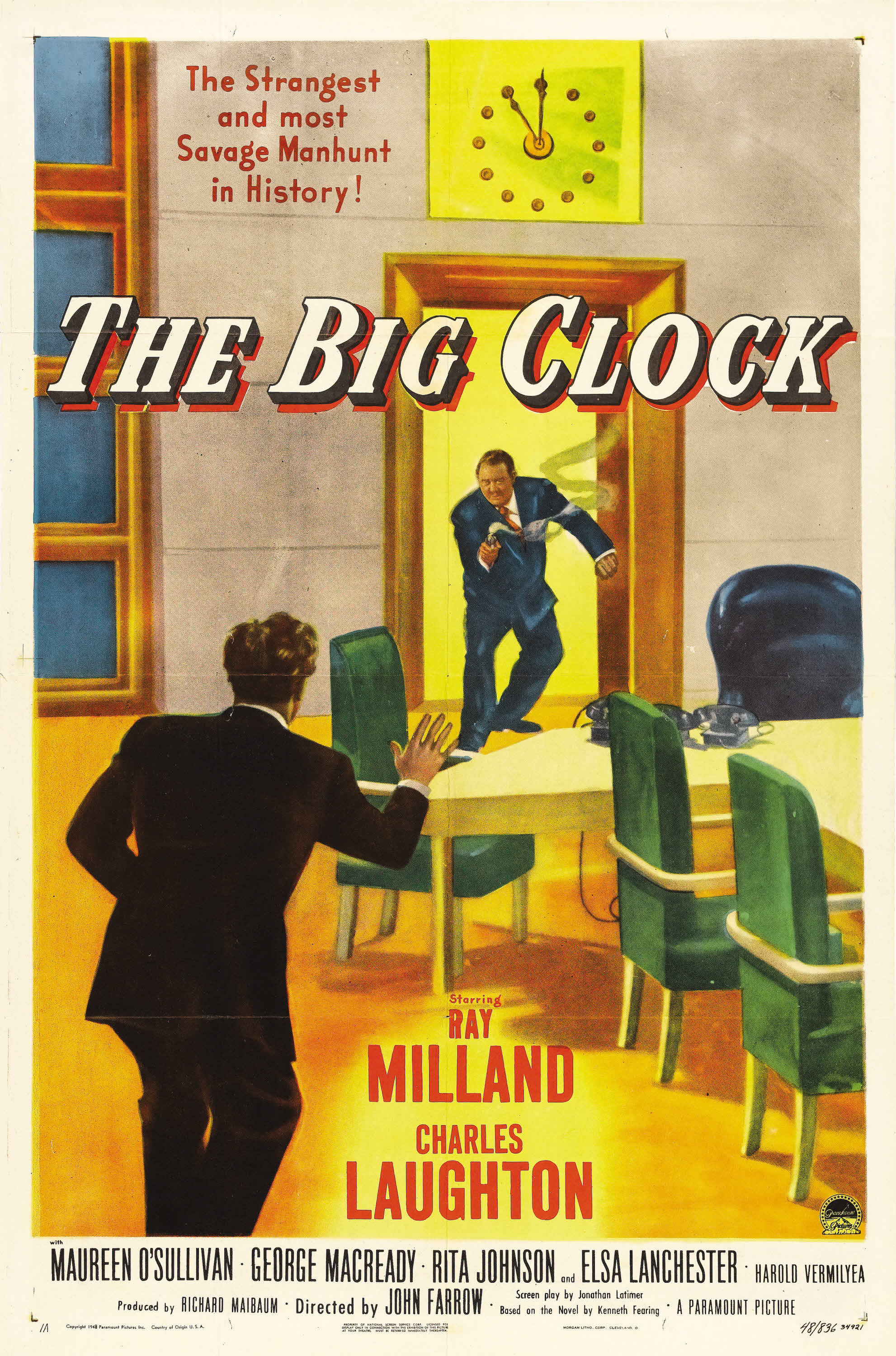

My first exposure to The Big Clock came from a now-defunct online crime fiction magazine called The Big Click (see what they did there?) named after the 1946 novel by Kenneth Fearing. What I didn’t know, even then, was that there was also a 1948 film version starring Ray Milland and Charles Laughton, never mind that said film version had been the basis for the 1987 film No Way Out, featuring Kevin Costner and Gene Hackman taking over the roles initially essayed by Milland and Laughton.

The ’87 version ups the stakes by making Hackman’s character the Secretary of Defense while Costner plays a Navy lieutenant commander. This turn toward the realm of political thriller – along with a pivot in the relationship between our protagonist and the murder victim – changes the tone of the story, moving away from the screwball comedy elements that make the 1948 version feel so light on its feet even as the springs of the titular clock wind tighter and tighter.

In the 1948 version, directed by Mia Farrow’s father John, Ray Milland plays a journalist named George Stroud who is working the crime beat for one of the many mags put out by mammoth Janoth Publications. Though we meet him in a framing flash-forward that shows him already on the run, hiding inside the titular clock, when the film then jumps back 36 hours, we see that he is, perhaps, too good at his job, tracking down people whom even the police can’t seem to find with the help of “irrelevant clues” which his team records on a blackboard in the Crimeways magazine office.

Laughton strides onscreen as Earl Janoth, the head of the company who manages the time and behavior of his employees as exactingly and as unscrupulously as the massive clock which sits in pride of place in the lobby. A tour guide tells visitors to the building about the eponymous big clock, an art-deco piece of architecture that tells exact time all around the world, to which all the clocks in the building – and, indeed, throughout the worldwide satellite offices of Janoth Publications – are connected, controlled by a “single master mechanism.” The clock, in this case; Earl Janoth, more metaphorically but no less accurately.

Laughton strides onscreen as Earl Janoth, the head of the company who manages the time and behavior of his employees as exactingly and as unscrupulously as the massive clock which sits in pride of place in the lobby. A tour guide tells visitors to the building about the eponymous big clock, an art-deco piece of architecture that tells exact time all around the world, to which all the clocks in the building – and, indeed, throughout the worldwide satellite offices of Janoth Publications – are connected, controlled by a “single master mechanism.” The clock, in this case; Earl Janoth, more metaphorically but no less accurately.

In proper film noir fashion, The Big Clock opens with an internal monologue from Milland’s character as he wonders, “What happened? Where did it all start?” Just the first of a film-long obsession with time and those pieces we use to tell it. Then, of course, we see where it all started – though the film takes some time getting there. While all of the elements of film noir may be on full display here, The Big Clock is anything but a typical example of the form.

In the booklet that accompanies the Blu-ray release from Arrow Academy, Christina Newland argues that The Big Clock’s preoccupation with the inner workings of workplace culture make it somewhat ahead of its time, prefiguring movies from the 1950s such as I Can Get it for Your Wholesale. Certainly, the ubiquity of corporate culture in The Big Clock – and the ways in which those same expectations and pressures warp the plot into its final shape – seem tailor-made for the big business ‘80s, making the decision to transform the ’87 Costner version into a political thriller all the more puzzling.

Ultimately, The Big Clock is as concerned with the toll that George Stroud’s work is taking on his marriage as it is on the murder that ultimately serves as the film’s inciting incident. In fact, it takes a full half hour before a murder has even been committed, half an hour more before the body is ever discovered. Before the crime that kicks everything off, Stroud has already been fired from his job for insisting on taking his wife and son on a long-awaited vacation – his first in seven years of working for Janoth – only to find that he has missed his train anyway.

Ultimately, The Big Clock is as concerned with the toll that George Stroud’s work is taking on his marriage as it is on the murder that ultimately serves as the film’s inciting incident. In fact, it takes a full half hour before a murder has even been committed, half an hour more before the body is ever discovered. Before the crime that kicks everything off, Stroud has already been fired from his job for insisting on taking his wife and son on a long-awaited vacation – his first in seven years of working for Janoth – only to find that he has missed his train anyway.

What follows is a series of set-ups that lead Stroud to being the in the wrong place at the wrong time. In a twist that could only come from one of these kinds of movies, however, Stroud is placed in charge of the investigation. It seems that Janoth, in a fit of anger, has killed his mistress – whom Stroud was carousing with that same night, while she attempted to rope him into a blackmail scheme against Janoth – and he intends to frame an unknown man for the crime. What Janoth doesn’t know is that the unknown man he puts Stroud in charge of finding is none other than Stroud himself.

It’s a setup worthy of one of Hitchcock’s wrong man capers, but while The Big Clock doesn’t hesitate to turn the screws, it often does so in ways that another suspense film might not. The back of the box avers that The Big Clock “classily combines screwball comedy with heady thrills,” and it is in those screwball comedy elements that the film excels in standing out from a crowd of similar fare.

From Stroud’s attempts to keep his wife (Maureen O’Sullivan) on his side to the flirtatious banter between him and Janoth’s mistress (played by Rita Johnson) to the antics of the other bit players who fill in the sidelines of the picture, nothing in The Big Clock goes to waste, yet the elements never feel as sterile and mechanical as the sets of the Janoth building in which so much of the film’s action takes place. Helping the film stay light and breezy are those screwball comedy elements, as well as a roving camera under the supervision of director of photography John F. Seitz.

More than anything, though, The Big Clock is an acting set piece for Milland and Laughton; not to mention a supporting turn as an eccentric artist by none other than the Bride of Frankenstein herself, and Laughton’s real-world wife, Elsa Lanchester. Milland plays a role he has essayed more than once as a straight man coming undone – as symbolized by the increasing disarray of his hairstyle – while Laughton commands every scene he is in as Janoth, selling both the media mogul’s icy control and his barely-checked rage, the latter accomplished with a sheen of sweat and a twitch of the lip.