The Devil is Only Human After All

Can there be supernatural horror without religion? If I take this question to the media products I recently consumed, the answer would be “Not that we know of.” Religion is as integral a part of The Haunting of Hill House as it is of Until Dawn. People pray when they are scared, they mourn the souls of friends killed by some horrific contraption and, most important of all, they believe. Or they specifically don’t until the monster that they refuse to believe in rips them to shreds.

Often there’s a clear dichotomy in believing in good and evil beings: the evil ones do not particularly care about us believing in them if they want to dine on our flesh; the benevolent ones only come into play if we think of them hard enough, often by praying or begging for help, whether they are heavenly messengers right out of the mythology of the respective media product or just humans saving other humans or themselves with newfound strength. And look, there it is, the point I am trying to make: “The good guys” often tend to be of a human aspect, either being the protagonists and side characters themselves or taking humanoid form as an angel or alien space traveler – yes, I’ll come to that. Meanwhile, the baddies are monstrous, betraying their intent in their aesthetics with red eyes, enormous bulky bodies and long teeth.

It is as clear a reference to biblical perceptions of mankind’s genesis as it can be: Man built in the shape of a benevolent god, contrasted by a monstrous force out to bring them downfall. A clear black and white, oversimplified, but effective. Yet even Christianity puts some grey in this equation: Lucifer has once been of the good kind, falling out of grace at a certain point. He is thus nearer to humanity than we may want to admit, and a lot of demons of the Ars Goetia, the index of 72 demons of King Solomon’s Book, take human form or feature some array of humanoid body parts, most often faces. The devil does wear more human skin than goat fur. This is inherently disconcerting to us. After all, we do not want to be like him, we would much rather be like Him, God, the ultimate projection of whatever we deem good and just at that time. And it is worthwhile to remember that most of the time those devilish or demonic features we loathe are just as human as the saintly virtues.

There is friction in this, more than enough for entire plotlines to revolve around it.

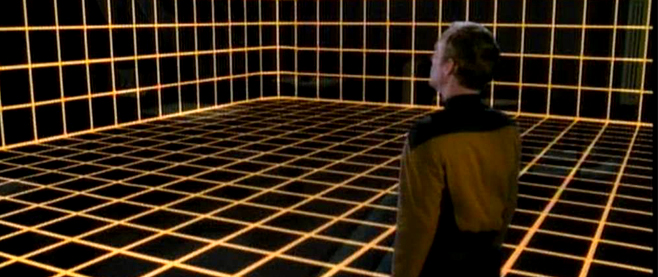

When David Tennant as the Tenth Doctor meets the literal devil in “The Satan Pit,” episode 9 of Season 2 of the rebooted Doctor Who series, ‘The Beast’ turns out to not actually be a god. As is always the case in BBC’s flagship sci-fi soap, everything supernatural is actually just alien and perfectly explainable through Deus Ex Machina pseudo-science. The devil is a hulking, extraterrestrial monster chained inside an asteroid prison rotating around a black hole by an ancient civilization. If the Beast escapes, the asteroid gets sucked into the hole, acting as a fail safe to contain the monster’s devastating mind-control ability forever. This mind control is what humanity fears, and how it came to know the being that it dubbed the devil. Through radio, radiation and general Doctor Who-y alien non-magic, the Beast can take control of humans, Ood and other lifeforms to do its bidding, with the long-term goal of setting the mind of the monster free and transferring it into another body so the actual husk can be hurled into the black hole without killing the devil. Developing rocket fuel so mankind can ascend into space? That might well have been the devil’s doing, in a grand scheme to be freed by the curious fools.

Knowing that Satan is not a divine being in the truest sense of the word does make Doctor Who’s monster a lot less spooky. It may be a cosmic being, and it may be incredibly powerful, but so is everything else in Doctor Who, including the protagonist. In fact, the Beast is just another one-off enemy, barely any more powerful than most other threats to the immortal time traveler, only standing out of the crowd a bit by being the antagonist in one of the rarer double features. But in the end, it is way more relatable to the human and human-like protagonists of the series. It’s a different species of lifeform, yes, but it nevertheless is a product of evolution, featuring some traits that humanity developed as well, such as a basic anthropomorphic silhouette and the ability to reason, to be cunning and cruel.

There is no hope of waving off the Beast’s cruelty as divine musings, something that cannot be understood. It is very much the one thing every human in a dire situation would relate to: the overwhelming desire to stay alive, to sacrifice someone or something else for their own survival. We eat; the Beast crushes minds so it can ride the empty husk out of its death trap. It even needs to breathe: One of the major plot points of the double feature is the Doctor wondering about the oxygen in the Beast’s prison and threatening to suck it out into space as a second failsafe option. When the devil is just a lifeform with humanoid traits, it loses all notions of a god and becomes an animal. And animals? Those we can relate to.

In contrast to the devil beast David Tennant casually throws into a dying star, the Dark Lord in Netflix’ The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina series is a much more potent, ever present, actually supernatural evil. What is more, “being evil” does not necessarily make the devil an actual antagonist to Sabrina Spellman. He wants to force her into selling her soul to him, sure. But when she does so at the end of the first season, she is no more or less a slave to the dark lord than any other member of the devil cult she and her entire family are part of. It’s a trade for which both sides know the stakes before signing the contract: Eternal burning in the fires of the afterlife in exchange for nigh unlimited power in the now, with the added clause that they must do the devil’s bidding in this life as well if he so demands. Sabrina is just more magically potent and thus more useful to the Devil than most of the other witches, making her a more valuable asset.

Truthfully, the devil of Sabrina is a capitalist: The CEO of Dark Church Inc., ever in a clinch with the rival Catholic church, they share an oligopoly on the harvesting of souls with. In one episode, Sabrina even finds herself before what could be described as a trade court, ruling over copyright and plagiarism issues because somehow, the name of the then infant girl found its way into the book of the devil, even though the girl had been baptized as a Catholic as well.

“Deal with the devil” has always had a very literal meaning in the sense that a trade with the devil will take something, but give something as well. More than a handful of fairy tales are based on this premise, and half of those deal with the especially interesting part of tricking the devil out of a deal, like for example “Timm Thaler or The Traded Laughter.” And that is the theme of a lot of the episodes of The Chilling Adventures.

One time, she uses the life force of one person to resurrect another, only to then resurrect the first one through some biblical miracle, hoping to trick nature into doubling the life essence needed for both bodies. What makes Sabrina stand apart from most fairy tales is that all of this goes horribly wrong: Nature is not to be tricked, and the devil as part of Sabrina’s universe is a manifested aspect of nature. That he takes form in a way humans can understand – a power-hungry schemer, a merchant, a humanoid goat – is only because he externalizes what he knows to be the essence of the humans he deals with. Their most essential interaction with him is a short-sighted deal, the here and now for the whole of eternity, often to the misfortune of the people around those witches that trade with him.

It would be weird for the devil to take any other form than the merchant of misery that relates so much to the desires of his underlings. How very human he makes himself in this becomes apparent in those instances where he can actually be tricked; when he has to barter with God for Sabrina’s soul in front of a judge, he has no more tricks up his sleeve than a defendant in trade court.

There is no bugdevil in Hollow Knight akin to mankind’s dark lord in The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina or the Beast in Doctor Who. Instead, there is the Radiance, an old, not necessarily evil god, but its benevolence towards its subordinates differs depending on the species of bug. To the moths, the Radiance is the all-mother and possibly quite literally so, since it is hinted at that it may be just a very, very powerful old moth. To the regular bug citizens of Hallownest, it is nothing more than pure carnal temptation, much more similar to an actual devil figure. The weaker of heart flock to the Radiance like figural moths to a flame, because the solution it proposes for living and being happy is an easy one. Whoever succumbs to the Radiance’s sweet touch degenerates into a being of pure instinct, into an insect just as we derogatorily use the term. Taking the Radiance’s light in erases all hints of free will in the anthropomorphized Hallownest insects.

And indeed this seems to be the natural state of things, from before the Pale King took the mythical Wyrm’s power and gave even Hallownest’s lowest bug consciousness and conscience. In this, Hollow Knight turns the biblical creation myth on its head: The Radiance does not blight bugkind into something twisted like the Snake supposedly did to Adam and Eve, it returns them into their natural state. The snake, in Hollow Knight’s case, is the Wyrm, its power wielded by the Pale King. Giving bugkind the insight to develop machinery, wear clothes out of shame, even walk on two legs is what disrupted the natural order of the bugworld. So in reversing this and leading insects back to a life in pure instinct, the Radiance makes itself an instrument of nature, whether she is actually a deific embodiment of it or just a living being old enough to know the former state of the world.

If there should be a counterforce to the Radiance, a God to it’s Devil, it would be the Wyrm itself. Yet in the course of the game we found out that it is dead; just an empty carcass of a once living, perfectly normal, if especially big insect-like being. “Being blessed by the Wyrm”, as the Pale King has been, is not an actual process of receiving the mercy of a deity; it means visiting the corpse of the biggest living being that ever existed, and meditating until you develop skills you never imagined you could get. Whether these are actual gifts of a supernatural force embedded in the carcass or basically self-improvement fueled by superstition is as unclear as the true nature of the Radiance. Both god and the devil might well be animals that somehow found themselves in a place of being worshiped by others, accidental monarchs to a flock of willing peasants.

There is horror in all of those depictions, even if their takes on the supernatural drastically diverge from one another. Whether the devil is so human it hurts or whether it takes away our humanity intentionally, it touches a part of our subconsciousness that we tend to lock away in a functional community. When we finally see that the devil we fear most is our innermost nature, the horror of confronting him or it works best. In reality, we do not want to sacrifice friends or tear down effective social structures in an attempt to satisfy some animalistic urge. Yet in a lot of media productions, we all too easily do.