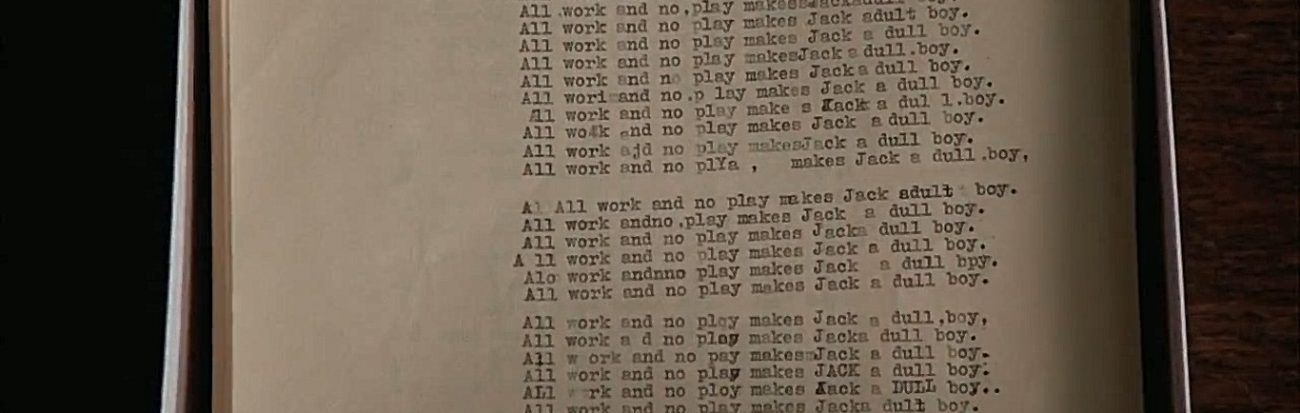

A Story of Crunch

There’s been an awful lot of news about crunch at videogame companies recently, and it’s never the good kind. Just for clarification, the good kind of news would be “Studio That Relied on Permacrunch for Years Breaks the Cycle,” “Studio Staff Happy and Making Great Games,” or “Shareholders Decide to Invest in Mental Health Initiatives for Studio Staff.” These variations I like to call “utopian Onion articles.”

We agree that crunch is harmful and a reliance on it unsustainable, and the more stories come out surrounding it, the more I yearn for a hopeful story of studios that are doing, even though such a story may also currently feel like pouring salt into a very fresh wound.

Recently I’ve worried less about the people who speak up against crunch and who reveal the environment they’re working in, and more the people in the margins of these reports, the people that don’t speak up, less because they’re frightened and more because in a weird way they might actually be fine or at least think they are. The road to burnout is surprisingly long, and it’s paved with good intentions only.

For me it has been seven weeks and two days since I’ve last stopped working for more than a lunch break, and for a little over four weeks I’ve worked around 105 hours a week. I can honestly say that it took me several weeks to even realize how much I had been working. That’s the passion argument – it’s fine as long as you enjoy it and there’s always something to do. There’s more to it than passion, a large part of what made me add to my workload is gratefulness, too. It’s only now that I realize how insidious gratefulness is – up until recently I’ve never had to talk myself into doing work I accepted, simply because I was grateful that it was there, the ideal, much-desired state for a freelancer.

I was proud, too – proud of how much I got done, proud of how I could uphold a certain standard even under pressure. Every element that lead to me crunching was simultaneously one that reinforced my belief in my skills. Last but not least, the element of self-portrayal: if I have a lot of progress to show for, in an environment and an industry where everyone is a supporter as much as they can turn out to be competition, I look busy, people won’t forget about me, and work will hopefully beget work.

My personality contributes to me regularly risking burnout. As part of a working class family, I was brought up to understand the importance of having work, and of doing it well, thoroughly embroiled in the capitalistic mindset that I’m at my most useful when I’m working, adding to a conversation, having an opinion. Add to that the pitfalls of creative work; ideas can be like fairy dust, and as long as I have them, I should use them. This leads to thinking about work or work-adjacent topics when I’m not actively finishing something.

I also want to lay blame at the door of the videogame industry, if you want to call it that, simply because it’s an industry that feels much smaller than it is, in which I genuinely want to exchange ideas, even if it doesn’t lead to me making money from it. Most of my friends work or have an interest in it, the topic inevitable. It’s a multi-billion dollar industry in which news break and games release with such regularity that I feel the need to ingest all of it, never knowing what may become relevant tomorrow, next month or even years down the line at the end of a development cycle. Games are my hobby, I used to follow news just because I wanted to, but the importance of being up to date in a work-context adds a certain weight that goes beyond simply keeping informed.

It leads me to wonder if a job can truly be a hobby, if I could stop myself from dissecting a game for potential ideas. Then again, it’s been weeks since I’ve played anything just for fun.

I can appreciate the irony of sitting here at 9pm on a Sunday writing about my burnout instead of doing anything else, but it’s something I wanted to talk about simply because of the way it crept up on me, and despite everything I’ve written so far to investigate the whys and hows doesn’t help this complete sense of bafflement.

I didn’t mention it because I didn’t want to seem incompetent, or ungrateful, I love my work.

I didn’t notice burnout sooner because of course I’d be tired, I work a lot.

I didn’t realize that it was burnout, not simply tiredness, when the job I job I love and everything associated with it, feedback from colleagues and friends, the feeling of achievement, the fun, simply meant nothing to me. Not once had I stopped and asked myself “what am I doing this for?” not even at times when the question was justified, among hate mail and the fleeting nature of writing something and watching it disappear into the ether, unacknowledged. I became a cynic, something I actively avoid, damning the videogame industry and everyone that tried to highlight good parts of it when damning it was an understandable response. I peered enviously at the work of colleagues, people with ideas, theories and a genuine joy for playing. Lastly, I looked at my work and hated all of it. I’ve always been my own worst critic, lately when you tell me something nice, I’m either completely unwilling to accept it, or accept it disbelievingly, just to not seem ungrateful.

I’ve nearly fallen down the flight of stairs from my flat several times in the last few weeks, I’ve forgotten appointments several times in a row and I’ve fallen asleep sitting up, hands still on the keyboard. I’ve worked over 500 hours in the last 5 weeks, getting up, writing, then sleeping. You can do that surprisingly well – even now the thought at the forefront of my mind is how things need doing and I can’t become sick or otherwise tap out now, and my body, held together by mental gaffer tape, seems to accept that.

We talk a lot about how inhumane long working hours are, how people who try to go home are kept from doing so, but simply working, simply moving on because the work needs to be done, can come to you just as naturally, and even once you do realise what’s happening, it’s astoundingly easy just to continue. I’m lucky enough to have very frank conversations with most of my editors about this, with everyone being supportive and telling me that breaks are necessary and taking time for myself won’t mean instant replacement, but the habit of wanting to be available, paradoxically especially because of their understanding and helpfulness, is difficult to break. I’ve become used to literally planning breaks around the gaming release schedule, and I’m always happy to change my plans in the face of a surprise announcement. I don’t yet know how to break these habits. Even now I can only slowly reduce my work, stop the three digit working hours a week until I can take a real break around a month from now.

As someone regularly going through crunch periods like this, especially now that every month in the industry feels like a busy month. I’m still looking for good solutions myself.