Friday Nights in the Hostile Environment

This feature story is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #111. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for nine dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This feature story is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #111. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for nine dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

In 2008, the Home Secretary of the United Kingdom, Theresa May, instituted an anti-immigration regime known as the ‘hostile environment.’ In the shadow of the 2008 financial crisis and fears of rising immigration from mainland Europe – legally, under the EU right to free movement – the regime’s stated aim was to make illegal immigrants feel so unwelcome that they would simply choose to leave, but in practice it was a broad psychological attack on the idea that anyone foreign should ever want to stay in the UK.

Over the following decade, the costs of residence visas soared while newpapers filled with stories of administrative cruelty, legal immigrants refused permission to work for the most specious of reasons, while widows and grandchildren of British citizens were deported to countries they’d never lived in. Banks, landlords and charities were saddled with mandatory ID checks for their customers and, in a notorious stroke of racist belligerence a fleet of vans was dispatched to patrol predominantly non-white communities across London, threatening “Go home or face arrest.”

While many of the more overtly offensive elements of the hostile environment were withdrawn after public outcry, the regime survived such amputations. Despite considerable research showing the positive effects of immigration on the UK economy and the reliance of crucial sectors of our infrastructure on a foreign workforce, for the past decade the hostile environment has been both the de-facto state of immigration in the UK and the defining policy of now-Prime Minister May’s political career.

Satire is a well-worn tool for the critique of unjust, discriminatory systems and, if done right, can promote awareness of the systemic flaws and disparities in a bad policy, or reveal the covert cruelty in an oppressive regime. However, getting satire right in videogames can be challenging, as it’s not sufficient simply for the narrative and setting to work towards the satire: the interactive elements of the game and the way the player involves themselves have their own subtext, and it’s all too easy for the message proferred by a game’s systems to undermine its narrative satire.

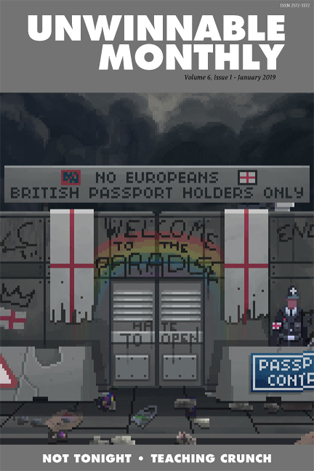

In much the same way that Lucas Pope’s Papers, Please satirized the immigration and oppression of Eastern Bloc police states, British developer PanicBarn’s Not Tonight offers a Brexit-flavored critique of the past ten years of the hostile environment. While Papers, Please directly addressed its theme by through making you work at a border checkpoint, Not Tonight applies a layer of abstraction by mapping the bureaucracies of border crossings onto the job of a nightclub bouncer.

In play it cribs from the Papers, Please school of administrivia: each pixellated reveller hands you their ID in turn and you check it against your list of allowances and restrictions. Their eighteenth birthday isn’t until next week, so they’ll have to try their luck elsewhere. It’s Wednesday, and their ticket’s for Tuesday, but they’re willing to slip you twenty quid if you look the other way. This man is wearing the wrong shoes. That woman is on the guest list, but her name is misspelled. Do you have time to check if their ID is a cheap forgery, or have last orders just been called and your nightly bonus relies on you getting one more punter across the threshold?

The fluid boundaries of human circumstance are reduced to a binary bureaucracy, and each time a petitioner fails one of its labyrinthine criteria the hostile environment delights in denying their entry.

On March 29th 2019, the United Kingdom will exit the European Union.

Brexit is the most divisive issue in this country for decades, and the increasingly likely “no deal” exit would be an act of extreme national self-harm, shown to be exceedingly unpopular in recent polls. At its core lurks the same deep-seated hatred of foreigners that drove the hostile environment, a hatred fanned and fueled by decades of anti-migrant tabloid headlines and the repeated political use of immigrants as the go-to bogeyman for the poor and dispossessed. You’re not poor because we failed to provide jobs or a sufficient safety net; you’re poor because they came here and took what’s rightfully yours.

True to form, the Leave campaign relied heavily on racist advertising depicting an endless sea of immigrants threatening to crash upon British shores, while Theresa May’s proposed withdrawal agreement is obsessed with ending free movement between the EU and the UK. EU citizens already resident will be required to apply to stay in the country they may have lived in for decades. The hostile environment cares not whether the foreigners it affects are here legally or not. Make them want to be elsewhere, it whispers. Make them go home. It cannot comprehend that home may be right here.

This is the conceit behind Not Tonight‘s dystopia, which extrapolates the after-effects of an extreme right-wing Brexit where citizens of European heritage – derogatorily, ‘Euros’ – are considered a sub-class of British society. You may have been born a British citizen and lived your whole life in this green and pleasant land, but without sufficiently documented ancestry you’ve been rounded up, forced to live in a ghetto and arbitrarily assigned a job suited to your low station.

Ostracized by your countrymen, bullied by your overseer Integration Officer Jupp and forced to raise exorbitant sums of money each month to fund your transitional residence visa – an ephemeral hall-pass hardly worth the paper it’s printed on – you take up your role as bouncer at a succession of down-on-their-luck pubs, scabby nightclubs and drug-fueled music festivals across the south of England. If you don’t make enough to pay your rent, bills and the increasingly ludicrous levies and administrative costs of being a supposed foreigner in a country staunchly committed to xenophobia, you’ll be on the next boat across the Channel.

In no time at all your job amps up in complication, xenophobia and classism. As the fictional far-right ruling party Albion First begins flexing its tyrannical muscles, simple checks of valid ID and matching names against guest lists are superseded by restrictions on specific nationalities, income and social scoring. Special assignments pressed upon you by Jupp see you travelling further afield to police border crossings on the south coast, and restricting commuter travel in and out of London, forbidding access to undesirable occupations (such as writers and journalists) and keeping the unwashed masses from cluttering the streets.

As satire goes, Not Tonight isn’t especially subtle, and despite its outward social commentary it leans heavily toward traditional British farce, awash with self-important buffoons talking past each other. Officer Jupp is comedically petty, a vicious jobsworth out to make himself a quick buck while making your life a misery. The Resistance who contact you to help bring down Albion First are utterly inept and spend more time working through teenage angst than offering meaningful rebellion, while your various employers are socially awkward, racist or stoned out of their minds. The vast majority of partygoers are randomly generated agglomerations of clothing and identification, while guest lists are populated with recognizable but thematically incongruous names.

Moreover, the analogy of bouncer-as-border-control suffers when it collides with the reality of your character turning away immigrants at the actual border. The requirements of documentation are stricter, but there’s no sense of the difference in impact between being turned away from a night’s revelry compared to being denied a chance to live or work in another country. Refusal is met with the same mildly-disappointed platitudes in either case. Papers, Please forced you to make difficult choices about the lives of those trying to cross the border; here, all too often the only thing at stake is your paycheck.

Despite its occasional narrative inconsistencies, it’s clear that Not Tonight considers both the hostile environment and Brexit to be terrible ideas. Your increasingly tyrannical criteria to turn people away harkens back to the growing restrictions on immigration instigated by the hostile environment, and the game’s interpretation of Brexit is shown to be the direct cause of broken relationships, international terrorism and the rise of the far-right to a totalitarian state. Nothing about the narrative framing suggests this will have a happy ending, except that certain design choices threaten to leave the player with mixed messages.

Not Tonight’s biggest flaw is that it wants to be fun more than it wants to be satirical. One of the quirks of bureaucratic busywork games is that they can all too easily feel just like work: Papers, Please leaned into being a harrowing critique of bureaucracy by being relatively short and difficult, the tedium of your job balanced by the claustrophobic knowledge that if even if you excelled, even if you took bribes and successfully evaded the gaze of government inspectors you were still going to have to decide whether your family were going to have food on the table or fuel on the fire that night. In contrast, Not Tonight wants to be fair and balanced; it wants you to feel rewarded for your good work, and provides a sense of progression as you work night after night at each of its beautifully-realised pixel art locations. But when the topic of the satire is the systemic unfairness of the hostile environment, a fair and balanced system feels specious.

Your financial pressures grow with each passing month, but rarely as quick as your rising earnings. You’re promoted to Head Doorman at a venue by not screwing up for three nights – a remarkably generous career advancement programme – and with that bonus in hand it’s quite feasible to make £1000-2000 each night even without delving into the more lucrative illegal activities like taking bribes or selling a variety of illicit substances to passing clubbers. Where Papers, Please gave you a hungry, freezing family and asked you to make impossible choices with never enough money to go around, being reasonably competent at your job in Not Tonight is rewarded with enough money to fully re-fit your grotty rented apartment with a fridge, an upgraded bed and a host of quality-of-life improving gadgets, along with a whole wardrobe of cosmetic items as a money-sink for your ridiculous wealth. It wouldn’t be so absurd if your job wasn’t supposed to be the dregs of the market, the lowest rung of the ladder, so undesirable that it’s assigned by fiat to a stereotypical downtrodden immigrant class.

Despite Not Tonight’s overt liberal narrative its systems inadvertently reinforce the conservative belief in meritocracy and worship of the status quo. If you’re an immigrant you’ll be discriminated against, given the worst jobs and limited prospects, but if you only turn up for work every day and do your best you’ll be rewarded with a comfortable, secure life. By half-way through Not Tonight’s story, I had enough money in my account to pay visa fees, rent and utilities without a second thought whenever bills showed up, with a far more laissez-faire attitude than I ever had in real life when I was working a minimum wage job and barely making ends meet. While the narrative demonstrates how the hostile environment erodes society, the systems seem to suggest that a far-right isolationist state might not really be so bad, if even its most-maligned underclass has such economic mobility.

Perhaps most damning, the climax of the game takes the form of a mock trial where you’re accused of terrorism. In lieu of evidence, your various employers, friends and acquaintances come forward as character witnesses, both in your favour and against. Kind and charitable acts are balanced evenly against anti-social behaviour and outright criminal activity, and the final outcome depends on the calculus of all your actions. It’s a redefinition of the binary implicit in the rest of Not Tonight‘s rules: that if there’s a single criteria you fail to meet, you’re turned away without recourse or means of appeal. While it may have been too punishing to hang your happy ending on the same zero-tolerance policy espoused by the rest of the game, it misses the whole point of the immigration regime it’s satirizing. The hostile environment isn’t fair, it isn’t balanced, and disproportionately punishes the slightest infraction. Meanwhile, the judge is quite happy to forgive your drug dealing and trade in foreign contraband as long as you’ve been kind to strangers and turned up to work on the regular.

Considering the success of Papers, Please it’s surprising that there have been only a handful of games exploring similar themes. Where Not Tonight succeeds is in invoking a very British descent into totalitarianism, and could have been a scathing indictment of both Brexit and May’s dream of draconian immigration reform. However, in contrast to the tone of the narrative, its systems promise that as long as you’re a Good Foreigner, if you keep your nose clean and do all the dirty work those in power demand of you, you’ll be well rewarded and your transgressions along the way will be forgiven.

Given what Not Tonight otherwise has to say about capricious, vindictive authority, it’s a regrettable conflict, one which no amount of bureaucracy can quite paper over.

———

Rob Haines is a writer, itinerant datamancer and unrepentant cat-dad. Read more of his work at https://robhainesauthor.tumblr.com/ or find him on Twitter @rob_haines.