The History of Twitter’s Little Bunnies

This column is reprinted from Unwinnable Monthly #110. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is reprinted from Unwinnable Monthly #110. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

Memes are the language of the internet, a natural outgrowth of an increasingly digital age. Memescape dissects them in the hopes of finding some sort of explanation beneath the collective lol.

———

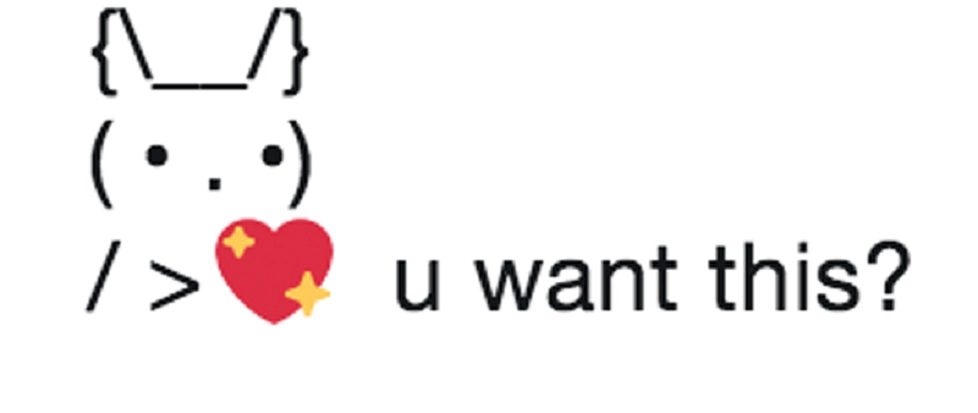

Last month, bunnies took over Twitter. Made of text and with messages limited to the platforms 280 characters, they stole our hearts quite literally, holding them just out of reach while taunting, “u want this?” before offering a stipulation.

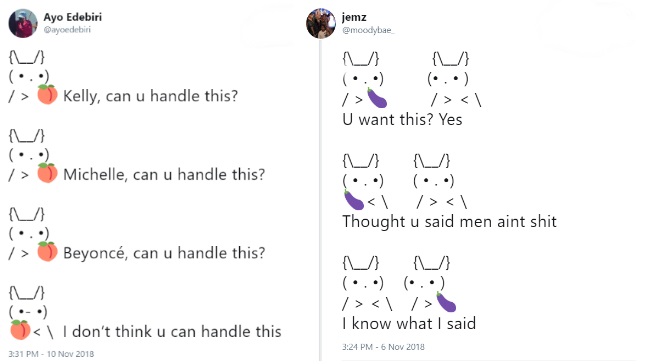

Some used the format to denounce Android users, others to entice their followers to vote, but, mostly, Twitter users employed the meme as a commentary on relationship standards or to playfully call out their own insecurities (one that personally hit home stated, “never ask me how the writing is going”). With the meme’s low barrier to entry given its text-based icons, internet denizens quickly began manufacturing their own variants with twists on what had already become a familiar formula.

After one user posted a scene of the same bunnies tossing a football back and forth, the floodgates open. Nothing was safe as users referenced high and low culture alike, deploying the bunnies in everything from breakdowns of The Little Mermaid’s central conflict to nods to Fortunado’s fate in The Cask of Amontillado. One popular iteration that garnered nearly 300,000 likes simply used the bunny to show how a cocktail is made.

Like many of Twitter’s recent memes, the “u want this” bunny originated back in the early 2010s but saw a resurgence after the platform doubled its character limit last year, prompting new takes on a format that, until recently, had been isolated to one corner of Twitter. In this meme’s case, it’s popularity can be traced back to Brazilian Twitter circa 2013, where what looks like its first iteration seemed to harbor a political edge modern examples lack. “U want this? Start talks with the International Monetary Fund” it posits in a message one can only assume is to the user’s country of origin.

However, given the bunny’s origins, such a political slant makes sense. You see, this isn’t the first time Twitter’s fallen in love with the little text art rabbit. In that same year, Spanish-speaking Twitter began circulating what became known as Protest Bunny, ASCII art rabbits holding signs filled with hot takes and political commentary above their cute, expressionless faces. It caught fire among media Twitter, spreading into the mainstream after a Tumblr employee, Amber Discko, used the bunny in a response to a tweet from The Daily Dot editor Cooper Fleishman. She later used the meme to remark “What did I start” as her followers began retweeting their own versions and it quickly blew up. Over the summer of 2018, protest bunny saw its own minor resurgence – no doubt precipitating the “u want this” meme – after historians started the trending hashtag #HistorianSignBunny to share esoteric historical tidbits.

These bunnies are far from Twitter’s first brush with ASCII art memes. The flamboyant text art Dancing Man meme, also started in 2013, lept back into the public conscious earlier this year accompanied by markedly darker humor than it had before. There’s also the Sleeping ASCII Cat, used to express existential dread and excitement in equal parts.

But what exactly is ASCII art? ASCII art comprises images using the 128 characters outlined in the American Standard Code for Information Interchange, basically the standards that govern electronic communication. While text art has its roots back in ancient civilizations in the form of concrete poetry, ASCII art, in particular, goes back as far as typewriters have been a thing. Look no further than Flora F. F. Stacy’s 1898 “mechanical drawing” of a butterfly, included in the 2014 book Typewriter Art, a Modern Anthology.

The ASCII art we know today in large part sprang from early printers’ inability to reproduce images, so they were limited to using those 128 characters in printed materials. This spawned enthusiastic communities of new artists creating images using different combinations of symbols, several conjugating on now largely defunct sites like GeoCities. Modern emoticons can even be traced back to their creations. Primordial internet users may fondly remember laboring painstakingly over ASCII art signatures in emails and on early messaging platforms, trying desperately to express themselves in the new landscape of the internet. Younger generations may recall later creations specifically made as memes like the Lolcano or ROFLcopter, which branched off into a subgenre known as LOL ASCII in the early 2000s.

The ASCII art we know today in large part sprang from early printers’ inability to reproduce images, so they were limited to using those 128 characters in printed materials. This spawned enthusiastic communities of new artists creating images using different combinations of symbols, several conjugating on now largely defunct sites like GeoCities. Modern emoticons can even be traced back to their creations. Primordial internet users may fondly remember laboring painstakingly over ASCII art signatures in emails and on early messaging platforms, trying desperately to express themselves in the new landscape of the internet. Younger generations may recall later creations specifically made as memes like the Lolcano or ROFLcopter, which branched off into a subgenre known as LOL ASCII in the early 2000s.

Despite its development well into the twenty-first century, Microsoft declared ASCII art dead in 1998, calling it “cute, but useless” and denouncing: “These things were cool in their day. The problem is, their day is over.” Well, Twitter has brought ASCII art back to life, heralding in a resurgence with its largely text-based social media platform with memes so popular in part because anyone can create and spread them in seconds.

During my research, I found a BrainPickings.org essay from 2014 that called the previously mentioned book on typewriter art “a beautiful allegory for how all technology is eventually co-opted as an unforeseen canvas for art and political statement.” How appropriate, I thought, that text art’s descendant would then be used for hot takes and political statements at the hands of cute, little bunnies. In a cycle that’s been continuing since mankind invented static symbols, Twitter has projected life into the lifeless, proving that even in the dull glow of all our screens, we can’t help but see ourselves.

———

Alyse Stanley is a trash can disguised as a journalist. She’s constantly knee-deep in fandoms when she’s not writing about video games. It’s been nearly a decade, and she’s yet to shut up about Fallout: New Vegas. You can find her on Twitter at @pithyalyse.