Hardware Digital Body

Off the sonorously quivering racket strings, the lob goes high – so damn high, the neon green ball spins clear out of the Billie Jean King Tennis Center in Astoria. Magically frozen below in mid-swing is the US Open match between Williams vs. Osaka, it’s biased referring still-to-come. The top-spun orb hangs in the air in front of the cloudy Manhattan skyline, drops, and hits the street, rebounding long through the open door of the Museum of the Moving Image. Inside, the ball bounces by a blue-LED-lit hallway; springs past a screening of Room 666’s eerie speculations about the end of cinema; ricocheting into an elevator playing animated gifs as art. Dribbling as though impatient, the ball waits while the elevator car rises. As this imagery commercial comes to an end, star-wipe starting, the tennis ball finally rolls to a stop in front of… Pong.

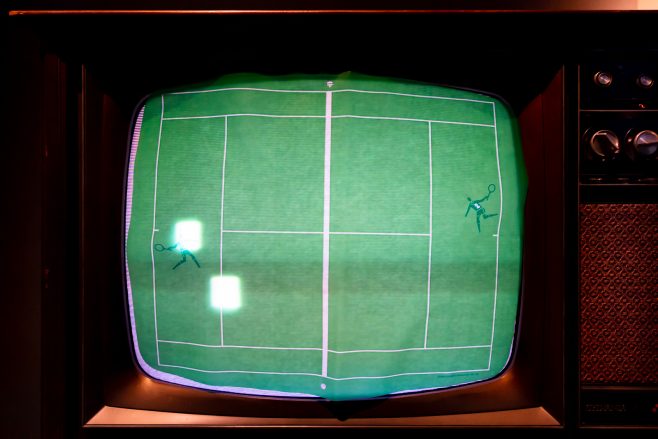

More specifically, it stops in front of four very different variants of the beloved videogame which demarcate the beginning of the show A Whole Different Ball Game: Playing Through 60 Years of Sports Videogames. “Boop… Boop… Boop…. Boop… Boop. BNNYAAAAAAAAAAA!!!!” barks the classic yellow woodgrain Atari Pong arcade cabinet. Nearby, a couple sits on the floor playing another version on the beige lump, Magnavox Odyssey, tissue paper with tennis players on it taped directly to a television rescued from a ‘70s den. Just over from the couple, an Atari Super Pong system showcased early versions of the paddle controllers that would become familiar to those of us who lived through the first console crash. On the other side of the room, with antibacterial wipes lounging next to mad-scientist wires and steel, was something I had only heard of: a version of Pong on an analog oscilloscope. Its acid green waves signaling a clunky videogame approximation of the 125 mph balls that Osaka can hit. Before you ask: Yes, it is Dark Souls hard.

This immediate conversation between these historical Pong-likes announces the curatorial intentions of Jason Eppink and his guest co-curator, John Sharp: the hardware and the player’s performance is going to be on the court together with the usually solo software titles. This focus on relationships is kept at the forefront throughout the many exhibits in the rest of the show, which is divided into short, thematic groups, such as “From Sport to Videogame” (a historical overview of game objects), “Playing With Data” (strategy and management games), “Sports Speculated” (science fiction-y works) and ending with “The Era of Esports.”

Maybe I could start with a snarky point about how little has changed in videogames over the past three decades since neither the Fortnite X-Box controller nor the LCD handheld games that infuriated kids on road trips throughout the 80s were playable on the day I visited. Both were out of batteries. #Galaxybrain or something. While that is too glib, I want to stay with the practice of putting the works in the show into relationships with each other, since it is where I feel as though the show is at its most productive. Encountering all these very physically heterogeneous games in boisterous conversation with each other let me access something that is too easy for someone who plays or writes about games to forget: the deeply esoteric skillsets and knowledges we learn and access playing videogames.

For instance, in one corner sits QWOP, where you struggle to micromanage the muscles in a human leg with infamously awkward results. The strangeness of the input devices and the skills we must learn to play videogames are also highlighted by the next work over, an NES accessory to use with Track and Field, the Power Pad. If you haven’t seen one of these, it is a floppy gray pad with painted circles that demarcate the controller buttons like some readymade vaporwave Claes Oldenburg sculpture. Both games are about running, but as anyone who cheated at the long jump by jumping off the pad and then back on can tell you, these two videogames demonstrate that however you try to map running to a digital game, that process is always defined by its limitations.

As if to highlight this peculiar relationship between our games and bodies, immediately next to these amusing games that train our bodies to perform digital representations of our bodies, is another brilliant pairing. Here, the display of our bodies is shown to be influenced by those digital performances in a series of eerily matched screens. Alternating displays show footage from baseball videogames eras alongside baseball television broadcasts to tease out how the visual vocabulary of videogames has deeply influenced sports broadcasting, from camera angles to cuts to data overlays.

Lest you think every work is about revealing the oddball novelty controllers, the section “Playing with Data” looks at strategic-layer and management sports videogames such as Championship Manager as well as their extended history in crunchy table-filled tabletop games like Football Strategy. One abstract aspect of videogames I have long struggled to articulate clearly made wonderfully legible here in the hardware-focused exhibit is workification. That is, when we play these job-like games as leisure, such as managing a football team’s budget in a gamified version of Excel running on a clunky white PC tower familiar to anyone with a cubicle job, it has this disorienting effect of collapsing our free time into our work-time. As though we can’t imagine a life outside of labor, we spend our evenings performing what amounts to part-time work in videogames, which itself looks entirely too-similar to the material conditions that went into the game’s development. Or, as Brendan Keogh puts it so clearly in A Play of Bodies, “The player’s body matters, to be sure, but not in a manner that can be presumed before an engagement with any particular videogame work.” In this case, it is a body ready to sit manipulating spreadsheet data long into unpaid overtime.

While I found the show deeply engaging, socially informative and filled with many useful physical touchstones to pry open oft-hidden aspects of videogame history, there were a few points that felt glossed over. I really wish it had included some criticism, such as Keogh’s, or Juul’s Art of Failure, to help explore our lived experience with games, as well as works of art made with sports games. Breaking Madden or 17776’s wry metaphors would have been the perfect way to open the conversation around how our media seems to have no vocabulary beyond the language of the market. I highly recommend to anyone who goes to the show to check out these works, along with Lana Polansky’s thinking about the dark gravity of capital in videogames and sports.

While staying clear of the role of money in games, the lack of gender equality in videogames and sports is at least touched on, albeit too briefly and without anywhere near enough context. The wall text for Tiger Woods PGA Tour 14 notes its awkward use of the Sony Move controller, but also for being the first time the Ladies Professional Golf Association was represented in a videogame… in 2013, which is over three decades of golf games and branded with a man notorious for his 2009 sex scandals. Similarly bereft of important context is the repeated use of footage of the StarCraft 2 professional Scarlett. Yes, she’s one of the greats, but her image graces a larger number of screens than there are professional women players in the rest of esports, which seems to obscure rather than highlight the ongoing discrimination against women, LGBTQ and people of color in esports, streaming and the videogame industry. Instead of looking critically at, for instance, Ninja’s Twitch chat to catch a glimpse of the latent status-drive of geeks, we are treated to a wall text for League of Legends, Call of Duty and other esports titles that flatly read “Too complicated for gallery play.”

Increasingly museums are trying to feature videogames in their esteemed halls. Yet the combination of vast architecture and press of quizzical bodies seem to inevitably jostle uncomfortably with institutional displays of videogames, which tend to replicate consumer electronics department displays, with middling demo loops on endless flat screens. Despite a few quibbles, the Museum of the Moving Image has produced a compelling show full of trailheads for visitors to expand their thinking about the embodied and contextual complexities of digital and videogame works. The show is also filled with useful strategies that other institutions and curators can learn from to better display videogames. Rather than seeing the tension between the physical and digital as a problem, A Whole Different Ball Game has leveraged the many inbuilt tensions of its subject, especially the slippery complexities of bodies interacting with hardware/software and the tangled relationship of videogames and sports, as a strong, sometimes comical, metaphor for how it feels to live through contemporary society’s body- and game-obsessed digital media maelstrom.

A Whole Different Ball Game: Playing Through 60 Years of Sports Videogames is on view at the Museum of Moving Image, 36-01 35th Ave, Astoria, NY 11106, through March 10, 2019. Visit here for more information.