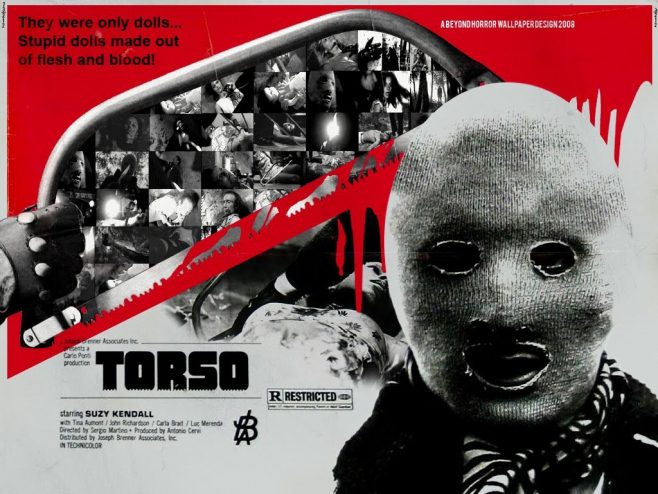

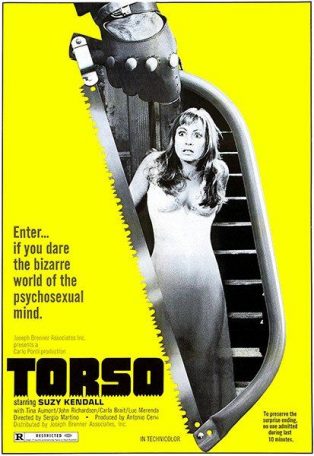

Of Giallo and Gore: A Review

“You will live through an experience that you now think no living creature can survive.”

– Torso (1973) & The Wizard of Gore (1970)

When I watched The Editor (2014) at a midnight screening at Panic Fest (this is going somewhere, I promise), it took me a while to get the joke of the film’s copious incidental nudity. At the time, I had seen only a handful of giallo films. (And, as of this writing, I’ve really only seen a handful more.) By about the mid-point of the film, I had figured out the joke, but I’m not sure that I ever really understood it until I sat down to watch Sergio Martino’s Torso for the first time.

For those who haven’t seen it, I described The Editor on Twitter as “if Anchorman had been a giallo,” and I still think that’s pretty accurate. One of its best gags is that, as the film goes on, background (and foreground) characters are just constantly naked at seemingly random times. The point at which I finally realized it was a joke and not just a stylistic choice was, I believe, when women were doing some light filing in the nude in the background of an office scene.

While Torso doesn’t have quite as much incidental nudity as The Editor, watching it definitely shows you why an homage/send-up of this kind of film would feature a joke like that. Which is a (very) long way of saying that Torso’s victims-in-waiting spend a whole lot of time in the altogether.

The days of squinting at pirated pay-TV channels in the hopes of catching a glimpse of flesh are long behind us, however, and a movie needs more than some bare skin to hold up in the modern day. Fortunately, Torso has a lot going for it besides its generous nudity.

Those who know me would probably assume (as I did for many years) that giallo films would not be my particular brand of poison. I tend to prefer my horrors more existential or supernatural; I’ll take monsters over murderers any day of the week, and, frankly, I have little patience for films that exploit suffering or make a point of victimizing women. Yet the best giallo films carry an air of weird menace that I find entirely mesmerizing and that always makes me completely overlook any of the elements that might otherwise turn me off. Torso is no exception.

In fact, there’s a quote early on in Torso, said during an art lecture taking place in an old church, that acts as a pretty neat summary of what draws me to the giallo genre: “Everything is bathed in an elegance approaching the supernatural.” While Torso may not quite reach levels of elegance that approach the supernatural, it makes extremely good use of its picturesque filming locations to create atmosphere out of little more than buildings and landscapes – and, of course, the music for which gialli are well known, in this case supplied by Guido and Maurizio De Angelis.

It doesn’t hurt that Torso is kind of a misleading title – the Italian original, which translates to “the bodies show traces of carnal violence,” is a little more accurate. In the insert booklet of the Arrow Video Blu-ray, there is an informative essay about Joseph Brenner, the distributor who brought films like Torso to grindhouse theaters in the states, not to mention giving them punchy, marquee-ready titles like, well, Torso.

Giallo films in general – and Torso in particular – are often held up as precursors of the slasher movie, and you can definitely see it in the structure of this picture. The obligatory kill shots are all here, and were probably shocking enough for 1973, but don’t seem like much compared to the kinds of gore most horror fans are used to by now. Actually, a surprising number of the kills in Torso happen off camera, and even the infamous scene of bodies being dismembered via hacksaw – from which, most likely, the film draws its American title – is more suggestion than show.

What is more apparent in Torso is the link between slasher films and voyeurism. Sure, there are the killer’s POV shots that we’ve all come to expect, but the themes of voyeurism come into play in many other ways, from the casualness with which the female characters treat Peeping Toms to the film’s opening scene, which features a threesome intercut by the clicking of a camera shutter.

What is more apparent in Torso is the link between slasher films and voyeurism. Sure, there are the killer’s POV shots that we’ve all come to expect, but the themes of voyeurism come into play in many other ways, from the casualness with which the female characters treat Peeping Toms to the film’s opening scene, which features a threesome intercut by the clicking of a camera shutter.

While Torso may not draw too many particularly novel conclusions about the male gaze, a Variety review quoted in the insert booklet points out that, “By the time the film is half over, Martino has strongly suggested that the dastardly deeds could have been done by just about every male in the cast…”

The film’s genuinely nail-biting third-act game of cat-and-mouse, which is more Hitchcock than splatter, also prefigures many elements of the home invasion films that would become horror staples in the aughts. Though, admittedly, most home invasion flicks don’t end with knock-down, drag-out fights between the rescuing hero and the killer – including jump-kicks! – so maybe Torso has them beat.

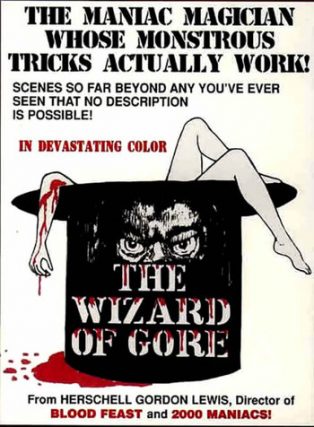

If Torso is a subtler film than you might expect from the title, The Wizard of Gore is pretty much what it says on the tin. Since I’m told that 1965’s Monster a-Go Go “doesn’t count,” this was my first real exposure to the legendary “Godfather of Gore” Herschell Gordon Lewis, who could just as easily wear the Wizard of Gore moniker as could the film’s eponymous murder magician.

While Lewis’s career includes a variety of grindhouse fare – and even a couple of children’s movies – he is best known today for his pioneering work in gore effects, which, per AllMovie.com, “prob[ed] the depths of disgust and discomfort onscreen with more bad taste and imagination than anyone of his era.”

Where Torso seems, at a glance, like a movie I wouldn’t like, but isn’t, The Wizard of Gore seems like a movie I wouldn’t like, and is. But I also learned a long time ago not to let a movie not being my thing stop me from enjoying what it does have to offer. Even famously bad movies like Manos: The Hands of Fate can have moments of unexpected effectiveness when you know how to look for them, and Lewis is a favorite auteur of my very good friend Adam Cesare, for whose sake I would happily keep my mind open through much worse. Besides, any movie that prominently features a restaurant called “Chicken Unlimited” can’t be all bad.

In some ways, juxtaposing Wizard of Gore against Torso is an extremely good way to appreciate this film’s modest charms. Lewis didn’t earn that “Godfather of Gore” appellation by being understated, and The Wizard of Gore pours on the red stuff, with homebrew gore effects made up of actual raw meat, bright red “blood,” and obviously fake mannequin heads. The result is disorienting and, at times, genuinely distressing, helped along as much as hurt by the fact that the amount of carnage wrought by the “tricks” of the titular magician doesn’t stay consistent from one shot to the next.

The grue in Wizard of Gore would probably already be striking, if not shocking, even to the most jaded modern viewer, but when you realize that it was made a full three years before Torso, and only a couple of years after Hollywood dropped the restrictive Hays Code, the full import of a film like this – and a filmmaker like Herschell Gordon Lewis – becomes even more apparent.

The grue in Wizard of Gore would probably already be striking, if not shocking, even to the most jaded modern viewer, but when you realize that it was made a full three years before Torso, and only a couple of years after Hollywood dropped the restrictive Hays Code, the full import of a film like this – and a filmmaker like Herschell Gordon Lewis – becomes even more apparent.

By far the best special effect that The Wizard of Gore has at its disposal, however, is Ray Sager as Montag the Magnificent. His confrontational stage performances not only provide most of the film’s suspense, but they are also filled with the thematic underpinnings that give the buckets of blood whatever heft they manage to have.

From the film’s opening moments, Montag practically berates the audience – both in his low-rent theater and, by extension, the audience watching at home – for their bloodlust and for their unwillingness to get their hands dirty for it, providing a kind of meta-commentary on the sort of picture that he’s in. “Today, television and films give you the luxury of observing grisly dismemberments and deaths without anyone actually being harmed,” he says, sometimes looking straight at the camera. There’s even a little nod to the way horror has changed over the years, when the film’s female lead says on her television talk show (Housewife’s Coffee Break) that Montag’s show made her more afraid than she’s been since “the Wolf Man left me quivering beneath the seats of the Bijou.”

Aside from Sager, Lewis populates the film primarily with non-actors with no other films to their credit, and the sets have the one-angle drabness of someone shooting on a shoestring budget. But “no budget” doesn’t mean “no imagination,” and The Wizard of Gore does a lot with a little. Montag’s guillotines and punch presses are bedazzled with glitter and little stars. There are sequences of red-filter night where a coffin rises from the ground at his bidding. And Montag’s hypnotism is conveyed, in grand old movie tradition, with a close-up of his eyes—or, in this case, mostly his eyebrows.

The Arrow Blu-ray of Wizard of Gore warns of scratches and audio flaws that are the result of the print not being in the best shape, but these anomalies serve to help the film’s bargain basement aesthetic more than they hinder it. The Blu-ray also comes with another feature film, a sleazy 1968 romp called How to Make a Doll. I’ll confess that I haven’t yet watched the whole thing. So, as of this writing, I still haven’t seen any other Herschell Gordon Lewis movies. I trust Adam’s opinion when he tells me that Monster a-Go Go really doesn’t count, but I can’t help noticing a surprising twin obsession present in the two otherwise pretty dissimilar pictures.

The Wizard of Gore’s surprisingly ambitious and almost apocalyptic ending takes some of the same ideas that were being listlessly batted around in the “as if an eye had been blinked” ending of Monster a-Go Go and runs them much more effectively home, transforming a simple enough gore picture into something that at least rubs up against the uncanny. While no one would ever accuse The Wizard of Gore of being “bathed in an elegance,” there’s no denying that the proceedings not only approach the supernatural, but probably go careening half-drunk across that line.

———

Orrin Grey is the author of several books about monsters, ghosts, and sometimes the ghosts of monsters. His stories have appeared in dozens of anthologies, including Ellen Datlow’s Best Horror of the Year. John Langan once referred to him as “the monster guy,” and he never lets anyone forget it.