Pivot

Too often, we cluster Metroidvania games into one big group, as if the subgenre descriptor is enough to tell us what we need to know about a game. And it often is. But even within the name itself, there’s a vast world of difference outside of the nonlinear exploration. The subgenre’s namesakes – Super Metroid and Castlevania: Symphony of the Night – are in truth vastly different games that happen to share nonlinear 2D platforming and exploration. And when you analyze how the two differ, you start to see the stratification and variety built into the genre’s very DNA.

The bedrock upon which Metroidvanias are built is in the feeling of exploration by designing levels in such a way that progression doesn’t seem linear, even if deep down there’s still an ideal route to take. This means instead of designing a 2D platformer with levels like a line, you design them like a layout to a building, except rather than an overhead view of the layout of each floor, you have blocks of levels that come together to form the world you’re exploring. You can see this in effect in both Symphony and Metroid, with their maps being dominated by rectangular shapes connected in circuitous yet sensible ways.

But the openness is often an illusion, as there’s always a certain order of progression you have to go in. New traversal abilities allow you to visit new areas until you finally get access to the final boss. So these levels are designed to feel like a layout, but what really ends up happening is that these traversal abilities act as pivot points for levels, making you backtrack as you find the new route that’s now open to you. Levels are actually still designed linearly, just with some vestigial bits grafted to them and coiled around these pivot points until they resemble a complex of sorts.

Super Metroid leans into this linear approach by both densely packing in as much hidden stuff as possible in the ancillary rooms while simultaneously making sure the rooms along the ideal path are spectacularly designed. It’s easy to overlook that the overall map for Super Metroid is actually quite small compared to other games’ because that density of things to do is there. And the game absolutely leans on that ideal path thanks to the many contextual clues it offers towards progressing – some worn-looking stones hiding a secret path you can bomb, perhaps, or a skeleton strategically placed to hint at something behind it. Yes, you can sequence break Super Metroid to hell and back, but when the path you’re supposed to take through the game is so clearly telegraphed, you know there’s some fakery involved, especially when you start playing the later levels that become super linear both in theory and feeling.

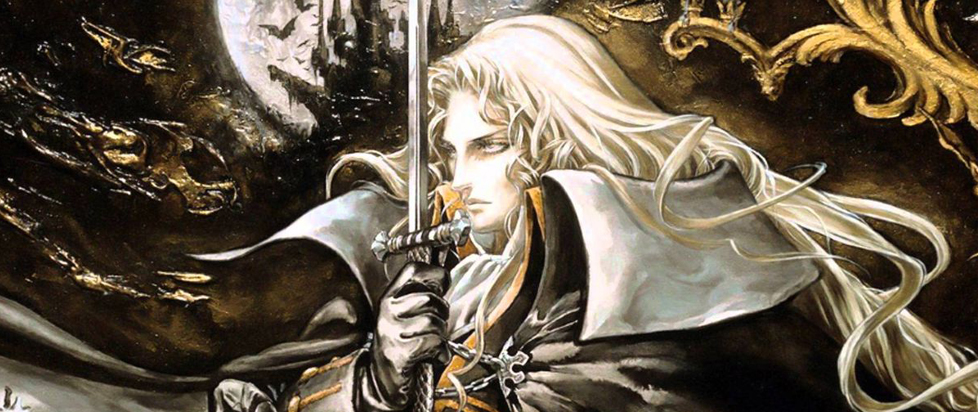

While Super Metroid does a lot with a little, Symphony of the Night takes the opposite approach and broadens the layout of its map, splaying out rooms everywhere. The same subtlety in level design found in Super Metroid is largely absent in Symphony of the Night. You’ll often find many straight stretches of hallways that are occupied by the same enemies over and over. While this could be construed as wasteful design, it actually serves a purpose: accentuating the combat and the RPG trappings the game takes on. The repetitive nature of the architecture means more time spent killing enemies, which is where part of the game’s heart lies. The other part is in the fact that the game’s pivot points are more broad strokes used to wall off entire sections rather than the next part of the path. This messiness of design means that players are free to truly explore instead of being partitioned into makeshift linear levels. And Symphony encourages exploration thanks to its multiple endings and de-emphasized ideal route. Best of all is the inverted castle you get to explore when you unlock the best ending, which is the same castle you already had been traveling through, but flipped upside down. You don’t have to unlock any part of the castle, as you already have all the traversal tools you need to explore every nook and cranny, so progression becomes entirely open as you try to find all of Dracula’s body parts held by bosses throughout the complex.

Neither one of these approaches are better than the other in the end. Super Metroid is a meticulously crafted, immersive experience that makes you feel like you’re exploring an alien world. Symphony of the Night is less concerned with the details, but offers the breadth to let you actually explore its world. The guided experience of Super Metroid is alive and well in games like Ori and the Blind Forest, while Symphony’s influence lives in Chasm and the subsequent Castlevania games that used Symphony’s formula. But breaking down why Super Metroid and Symphony of the Night succeed in such different ways is crucial for examining the genre at large and why putting everything under the umbrella of “Metroidvania” only tells part of the story.