Abstract Art

Games can play a clever trick on our brains by casting us as the most important beings in the universe. Because games place the audience in the driver’s seat of the art they’re consuming, it quickly becomes apparent that what happens in the game becomes a reflection of yourself. This can be problematic, as discussed in countless ludonarrative dissonance theory articles examining the fantasy vs. reality of killing so many enemies in Uncharted games. We see that in so many other games, too, such as Diablo III, where you’re basically holding a button down to slaughter everything around you. In Diablo III, though, this is the point, as the game is very much trying to tickle the right neurons in your brain with each and every kill, creating a pleasing feedback loop that makes the game addictive. But what does that say about us? Are we really that bloodthirsty? The truth ends up being both more mundane and illusory, as games are incredibly suited to taking real concepts and turning them into abstractions, perhaps even too well for their own good.

Take the Diablo III example and really think about it. What are you doing on screen? You’re using attacks and special moves to destroy any and all enemies in your path. But what are you actually doing to accomplish this on screen? You’re pressing buttons and holding a direction to attack in, either with mouse and keyboard or a controller. There’s nothing surprising there, as standardized controls means you’re going to be doing mundane things to look like you’re doing badass stuff on screen. But back up for a second. Pretend instead that we’re talking about Geometry Wars, the seminal twin-stick shooter game from the dawn of the Xbox 360. Now plug in what you do in Diablo III to the context of Geometry Wars and it still makes sense. Attacking requires a certain input as you use another input to move around. Another input activates a smart bomb effect, which can be the special moves in Diablo III. The commonality of control standards and design philosophy is undeniable, so it’s the audiovisual context that ends up making the big difference, right? Well, not exactly.

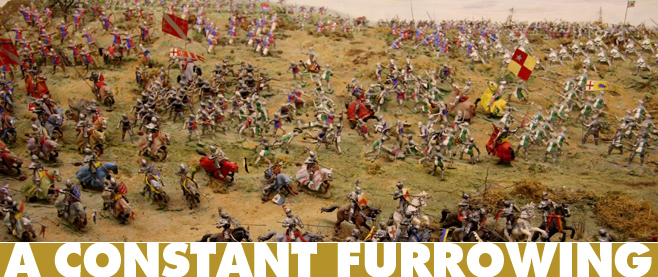

What ends up happening is you get into the rhythm of the gameplay loop so much that you zone out and attune yourself to the game. The demons and monsters disappear and are replaced by “enemies” for you to “defeat”. The abstract concept of what you’re doing overrides the thematic concept, and you’re caught up in the wave of hacking and slashing. It’s not an altogether bad sensation, mind you. Shutting off your brain as you defeat droves of enemies is compelling in every sense of the word in that it self-propagates its own compulsion through its gameplay loop.

But when you get right down to it, attuning yourself to the gameplay abstraction can make you miss the forest for the trees. Any thematic richness you might have culled from your audiovisual presentation is dulled by the loop. Part of the fault lies with the self-centered perspective most games cast you in. You’re so hyper-focused on your avatar and what they’re doing that you become myopic to everything else the game might be doing. So one of the logical solutions to this problem is to de-center the perspective – either make multiple playable avatars to take control of, or give players a reason to care about what’s happening outside of themselves. For as enjoyable as Diablo III is, it could have been so much more had it pulled either one of these things off.

The other solution is a more radical one but is becoming more and more feasible: virtual reality. By upending the control standards that games have been built on since the beginning and allowing for more natural, less abstracted actions. Because what you’re doing in VR is a one-to-one adaption from reality, you care more about what’s happening around you and you can’t help but feel immersed. Everything still revolves around you, but you buy into the artifice more because of how familiar doing things in this world feels.

We think of Diablo III and its ilk as a mindless point-and-click, and it’s totally okay that that’s all it aspires to be, albeit the best hack-and-slash on the market. But when you realize that all the set dressing disappears as you start to mow down wave after wave of faceless enemies, you can see that the abstraction hijacked the vision of the game itself. If games are to truly fulfill their potential, then designers need to be careful about how they utilize abstraction lest it engulf a game whole.