Hell is Other People

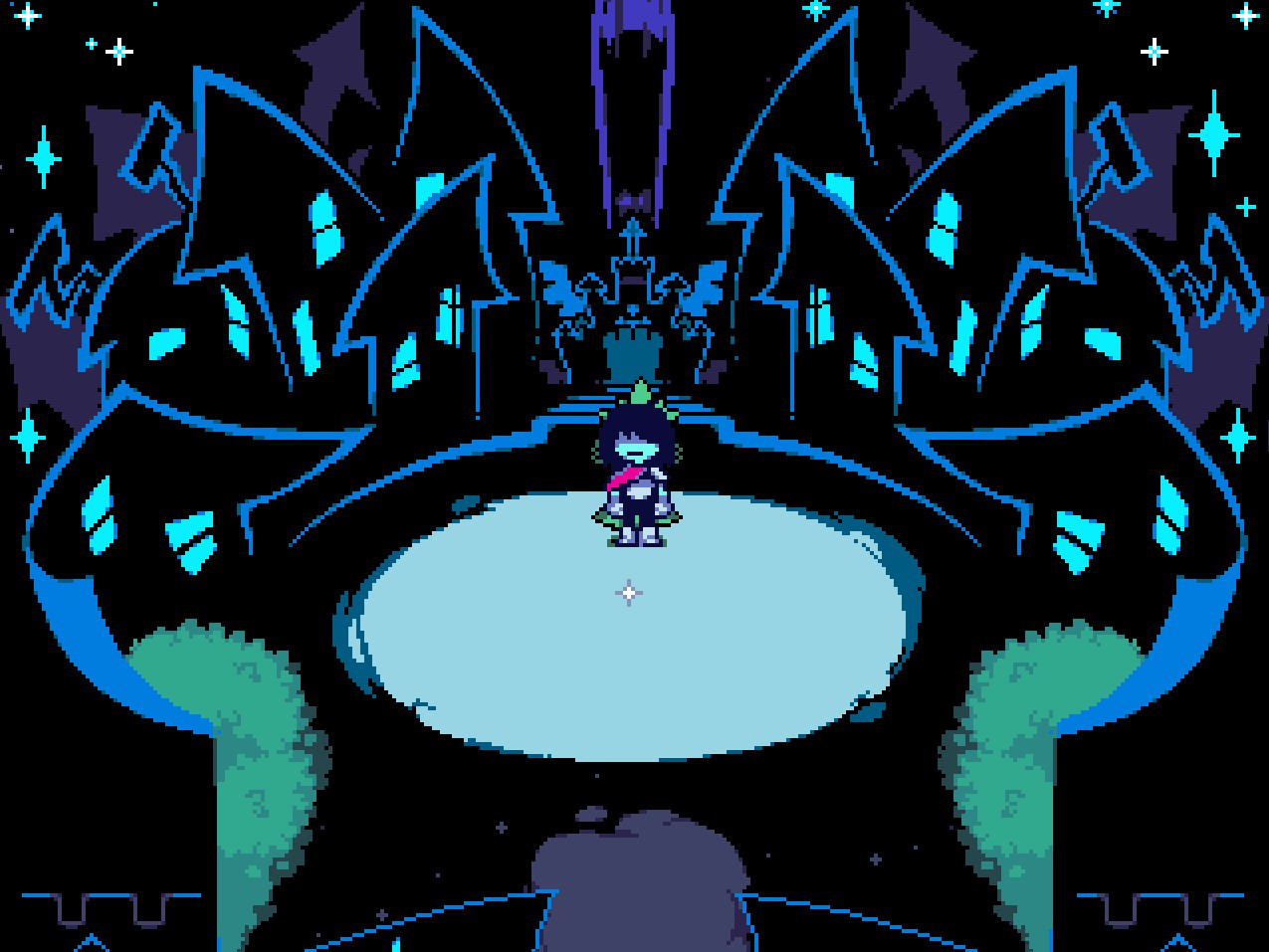

Undertale is a game that’s not afraid to make value judgments. All throughout your playthrough, it keeps track of every enemy you kill, and chastises you in the end for giving into temptation and killing off someone. It’s a statement meant to make us think about the implication of killing enemies in games, the ludonarrative dissonance of being cast as a hero whose body count reaches towards the ceiling. Undertale gives you the power to choose not to be a murderer, or to even murder everyone if you were so inclined. But whatever you decide, it makes you face those choices head on and asks difficult questions about your assumptions of videogames. But if Undertale is about questioning your own choices, then follow-up Deltarune is about how your choices and values are at odds with someone else’s, even a supposed friend’s.

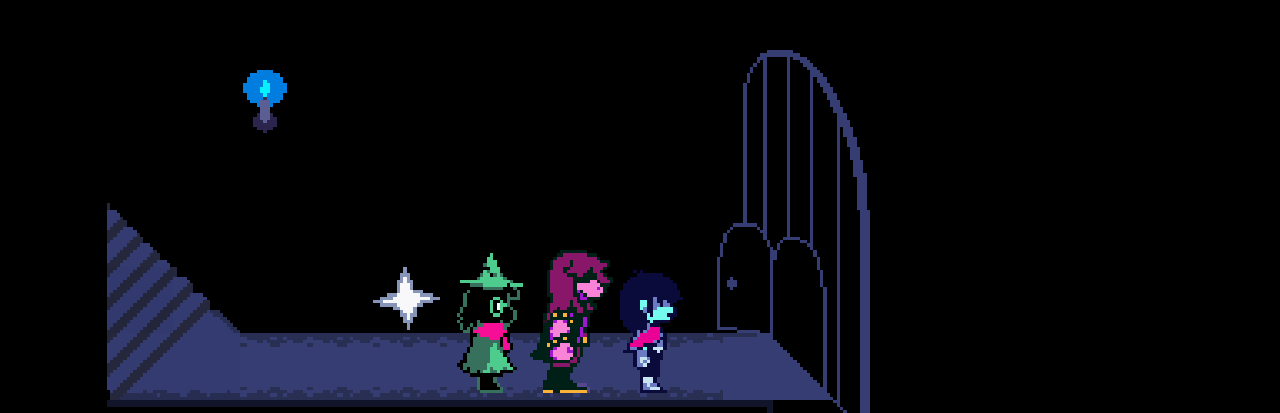

In Chapter 1, you play as silent protagonist Kris, but the chapter is really Susie’s story. Susie is a typical high school bully who falls into a strange, dark world with Kris as they try to find their way out. A big difference between Undertale and Deltarune is that Deltarune’s combat system allows for three characters instead of just one, meaning more options. The ability to Spare enemies once you’ve made them friendly, a key feature in Undertale, is still here, but there’s a catch: Susie doesn’t play nice. For most of Chapter 1, Susie will attack enemies relentlessly out of your control. If you plan on Sparing everyone, you need to Warn enemies about impending attacks to compensate for Susie’s violence, giving you time to find ways to Spare them.

Susie has no patience for sparing things that are in her way, declines to recognize the inherent value in others, and, indeed, you can join her in mowing everything in your path down. But if you want to ensure everyone lives, you need to compensate for her rampage, minimizing the damage she can do. Deltarune recognizes the shortcomings of Undertale’s message – facing the consequences of your actions by acknowledging other people exist, too, though their views might be harmful. Even if you’ve found ways to not cause harm to others in Deltarune, no matter what, you can’t control people, and that’s an important lesson to have in general. Sometimes you can’t convince people to care about other people. Sometimes all you can do is minimize the harm their lack of empathy leaves in their wake.

As it happens, Susie does change by the end of Chapter 1, but it has nothing to do with your actions. All through the game, a native kid known as Lancer antagonizes the party, but is too weak to do any real harm to them. At a certain point, Susie decides she’s bored with being a hero and joins Lancer on the evil team. After several humorous vignettes of them trying to make an evil plan, Susie decides to join the heroes again with Lancer in tow, but soon after, Lancer jails the party members as per order of his father, the king. Once Susie breaks out of jail and confronts Lancer, she can’t bring herself to kill him despite her rage. What’s more, she promises to Lancer that she’ll not kill him and find another way to deal with him. From that point forward, Susie can be controlled normally and can Act towards making enemies agreeable with the rest of the party.

[pullquote]We live in an age where those of us with empathy beg for everyone else to find some so the suffering in the world can decrease.[/pullquote]

Deltarune does end up letting Susie off the hook too easily. Her reformation doesn’t feel entirely earned when all she does is learn to care about one person – later more thanks to Kris defending Susie against the final enemy. Susie’s friendship with Lancer does reveal one truth about people discovering empathy, though: it comes first as a selfish desire, then grows out from there if it grows at all. So many people out there will only care about other people if they have a selfish reason to, because they’re related or they like a person. This is a phase we’re supposed to go through during childhood as we learn empathy out of our inherent selfishness. But some people never grow beyond that phase, only caring about people within their own orbit or sense of commonality. Susie just learned how to care about someone, and even then, that desire grows from her own selfish desires.

We live in an age where those of us with empathy beg for everyone else to find some so the suffering in the world can decrease, that people can live better lives. But time and again, we see people of privilege only caring about people like them, people they interact with daily and certainly not people they’ll never meet. We’re constantly told we have to win these hearts and minds, when in reality, they’re not going to ever leave their echo chambers, their sheltered lives, their selfish little worlds. The one hope we have in reaching these people is in bridging who they do care about with everyone else. If we can get people to see strangers like they see loved ones, then there’s a chance of personal growth. But we have to realize that not everyone will come around, and the harm they cause needs to be mitigated if they won’t find their empathy.

Undertale and Deltarune both come to us during very cynical times. They both ask questions about the nature of games and where they disconnect with our sense of empathy. But they have notes of hope precisely because empathy can unlock a world worth hoping for. Unearned or no, Susie’s redemption arc shows us a blueprint for a better world, and it’s one no less harsh than the times we live in: care about other people, or get out of the way. If that sounds blunt, it’s only because it speaks to the inherent drive and, yes, determination in true empathy.