The Harmful Misconceptions Behind We Happy Few

Back when I thought We Happy Few’s was just a 1984 or Brave New World ripoff, I thought its concept was charming. There’s something lovely about weaving together the hysteric whimsy of ‘60s Mod culture in Britain, a country going mad in its fashion and design to avoid looking at the world falling all around it, with a tale of masked emotions, drug abuse, and dystopia.

It seemed like a harmless enough premise: a dystopian society grown dependent on the mind-numbing effects of a drug, aptly called “Joy” in We Happy Few, with denizens addicted to the bliss it produces. Ultimately a benign if referential concept. Perhaps its a commentary on the opioid epidemic rampant in lower income areas, I thought, or maybe a postulation on the effects of celebrity drug culture.

When I found out Compulsion Games’ true inspiration, my opinion on We Happy Few instantly soured. A 2016 quote by the game’s narrative director, Alex Epstein, that started making its rounds on Twitter recently summarizes it so:

“We Happy Few is inspired by, among other things, prescription drug culture — the idea that no one should have to be sad if they can pop a pill and fix it. It’s also about Happy Facebook culture: no one shares their bad news because it would bring everyone down. As a culture, we no longer value sadness.”

The ignorance of that last sentence particularly riled me. In a time when 300 million people worldwide suffer from depression and suicide is the second-leading cause of death for young Americans, “we no longer value sadness”? As if to imply that 1) Using medication to counteract poor mental health is both an undesirable and easy solution and 2) That those who suffer from depression can overcome their medical disorder by simply embracing the emotions that disrupt their standard of living and, for many, even threaten their lives.

Such a statement is irresponsible at best and potentially harmful to those affected by mental illness at worst. Deficiencies in one’s brain chemistry cannot be overcome by embracing one’s sadness no more than a broken leg can be mended by welcoming pain. Yes, medication is not a solution for everyone, but that’s a decision best reached between a patient and their health professional, a discussion that many suffering from mental illness struggle to breach in the first place because of misconceptions that like those posed in Epstein’s quote.

And his words echo a longheld sentiment by the public conscious toward mental illness, particularly depression. The idea of antidepressants being some sort of magic “happy pills” took root in the ‘80s and ‘90s as their prescription became widespread with the development of a drug that tackled a specific brain chemical believed to influence happiness: serotonin. Psychiatrists feared that people even neurotypical people would begin turning to these drugs to influence their personalities and dash away gloomy fits, a form of “cosmetic psychopharmacology,” as coined by Dr. Peter Kramer in his 1993 novel Listening to Prozac.

And while there is some truth behind fears of overprescription, a 2017 study found that antidepressants have a “nonexistent to negligible” effect on patients experiencing temporary melancholy as opposed to a depressive disorder, defined by perpetual feelings of sadness lasting months, even years, that disrupt one’s everyday life.

[pullquote]“…most of the time, prescribing an antidepressant is not about making somebody ‘better than well’ but rather helping to relieve a patient’s acute suffering enough that she can resume a semblance of normal life.”[/pullquote]

Ironically, while doctors may have been quick to prescribe antidepressants in the past, evidence suggests that many people suffering from depression often go undiagnosed. An Archives of General Psychiatry study found that half of Americans with major depression either don’t get the treatment they need or take years before consulting a professional. Even Kramer later relented in his book Ordinarily Well that the concern for antidepressants may have been overhyped and delegitimizing for patients with real needs for the drugs.

“…most of the time, prescribing an antidepressant is not about making somebody ‘better than well’ but rather helping to relieve a patient’s acute suffering enough that she can resume a semblance of normal life.” The New York Times summarized.

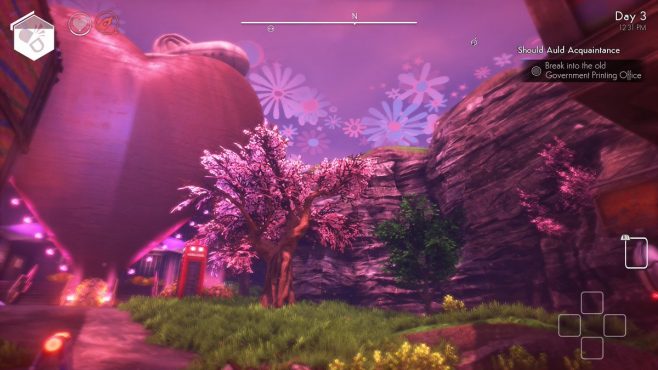

And yet the myth of “happy pills” persist, seen most recently in We Happy Few’s “Joy,” a drug the citizens of Wellington Wells are addicted to en masse that cheers them up and makes them forget their worries (quite literally, as a side effect is memory loss). I can only be thankful that the original commentary on anti-depressants seems significantly watered down for the final release.

The overmedication of the Wellies, as the townspeople are known, seems motivated not from feelings of melancholy or depressive thinking, but because of a shared unsavory past the lot would rather forget full stop. Compulsion Games frames Joy as a stopgap for their collective regret rather than an individual illness each citizen must address, and one that’s tearing their society apart at the ends. After all, “Truth is the enemy of happiness,” one character muses.

Still, learning the premise’s origins colors how I see otherwise benign gameplay elements. Experiment-crazed doctors wander around the streets sniffing out citizens who’ve gone off their joy, and I stop and wonder: Is that how Compulsion Games sees my psychiatrist, just a monster obsessed with doling out pills, forcing people to “take their medicine”? Or when your character, Arthur, takes a healthy dose of Joy (available in strawberry, chocolate, or vanilla flavors), and begins to cheerily swing his arms as colors and butterflies swirl around him; is that what the developers sincerely think being on antidepressants is like?

Ultimately, Epstein’s words cast the world of We Happy Few in a new light, obfuscating its attempts to create a dystopia. The aphorisms Arthur spouts as he’s hopped up on joy are the same I’ve learned time and time again in my therapist’s office. The compliment machines that offer what the game seems to jeer at as false niceties spew a lot of the same mantras I scribble on post-it notes and slather over my bathroom mirror. And while I’d never go so far as to say I’d like to live in a society like Wellington Wells, now that I know Joy is supposed to be an exaggeration of antidepressants, the concept isn’t entirely distasteful for someone who’s battled a lifetime of depression.

In short, if Compulsion Games really wanted to craft a world with terrifying implications, they may want to better understand the concept they’re building on: the often real-life hell of living with mental illness.