Don’t Go In the Woods

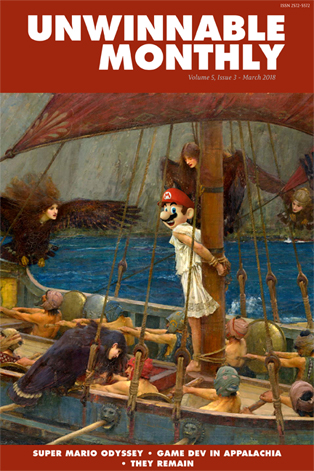

This feature is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #101. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

There is something foreboding about a forest. It is something about the way shadows gather under the twisted boughs, how sound seems muffled and indistinct. The primeval woodland is not for us. It marks a borderland, the dwindling edge of our civilizing pursuits. Even as we hack away and push back against it, it forever looms as a reminder of just how fragile the illusion of civilization is. How often do people head into the woods, never to return? What lives within the dark underbrush? And with what appetites?

The unease we feel when looking at a tree line is a deeply held, perhaps even evolutionary, reflex, and one explored again and again by horror stories and films. The variety of terrors the human mind has situated among the trees seems endless.

They Remain, a horror film directed by Phillip Gelatt and closely adapted from the short story “—30—”, by Laird Barron, brings us into a remote wilderness in the company of two scientists, Keith (William Jackson Harper) and Jessica (Rebecca Henderson). Isolated in their futuristic camp module, they search for environmental causes that might explain the strange animal behavior in the area – and may also have driven a Manson-like cult to murder decades ago. As they run afoul of a hostile and hallucinogenic genius loci, viewers and readers alike find they have a new reason to fear the forest.

They Remain, a horror film directed by Phillip Gelatt and closely adapted from the short story “—30—”, by Laird Barron, brings us into a remote wilderness in the company of two scientists, Keith (William Jackson Harper) and Jessica (Rebecca Henderson). Isolated in their futuristic camp module, they search for environmental causes that might explain the strange animal behavior in the area – and may also have driven a Manson-like cult to murder decades ago. As they run afoul of a hostile and hallucinogenic genius loci, viewers and readers alike find they have a new reason to fear the forest.

Gelatt settled on adapting “—30—” for a variety of reasons. His follow up to his 2011 film The Bleeding House had to be something that could be made on a small budget, had to challenge his skills as a filmmaker and, most of all, had to be strange – weird with a capital W.

“I had been a fan of Laird’s work for a while,” say Gelatt. “On my hunt for material, I started to pick through his catalogue. ‘—30—’ grabbed me almost immediately as something that would tick all those boxes for me. It was uncompromising and strange. It was contained yet expansive. It would afford me an amazing backbone of a world and story on which I could iterate and explore. And it was damned challenging as a horror story. There was no onscreen threat to use a crutch in terms of tension and gore.”

“And it had a line of dialogue that gave me chills every time I read it: ‘You have no idea what this is.’ It’s such a slap in the face and points the reader back towards a depth in the story they may not have realized was there. That line stopped me dead in my tracks.”

Gelatt took the story to his producer Will Battersby, secured the rights and got to work adapting the story for the screen. For readers of Barron’s story, that adaptation to film feels at once familiar and alien, provoking a reaction that verges on confabulation.

“A proper adaptation should fundamentally alter the source material in order to justify its own existence,” says Barron. “I’ve seen enough scripts and treatments over the years to have lost my naiveté regarding the adaptation process. It’s a testament to Phil and his team’s dedication to the source material that so much of my story survived the process. However, even the purest adaptation necessitates fundamental changes in the source material.

“People who’ve read ‘—30—’ deserve a fresh experience when they encounter it as a film. A film should either dig into the subtext of the original work or transform it in some meaningful way beyond the live action element. Good adaptations show us something new or important or somehow encapsulate the core of their subject. They Remain is faithful to the source, yet isn’t. I take perverse pleasure in comparing the story and the film.”

“I am a big believer that if you choose to adapt something, you shouldn’t be seeking to change it too much,” says Gelatt. “You pick material because you see something in it you love, so you need to preserve that as much as you possibly can. I thought of it almost like a Hippocratic oath: ‘Do no harm.’

“That being said, yeah, I had to change some things. The story is fairly plotless, so I ended up needing to string together a bit more cause and effect, to get things to work in a slightly more filmic way. I never did a proper treatment for the film – I printed out a copy of the short story and cut it into pieces. Then I glued those pieces into a notebook and started to fill in the gaps with notes and ideas and things that might [or might not] work.”

Which isn’t to say that They Remain is a heavily plotted film. Abrupt cuts and unreliable perspectives conspire to leave the viewer unsure what is real, or even when the characters are dreaming. Even the reasons for the two-person expedition are hazy. A growing sense of dread is far more central to the film than the unravelling of its mysteries.

“I have lately become vehemently anti-plot,” say Gelatt. “I think an excess of ‘plotiness’ ruins most fiction, in particular film. Too much is happening and it ruins everything.”

There is a lot of space in the film. Keith is tasked with placing and maintaining the motion-activated cameras in the sectors surrounding the camp. Much of the movie is given over to viewing Keith in relation to his natural surroundings – often, he is small in the frame, surrounded or even obscured by leaves and branches. The camera lingers on the small details of the forest – red ants sluggishly navigating their way through the brush, seeds on the wind, light through the canopy.

Barron hails from Alaska and lived for many years in Olympia, Washington, where great tracks of forest enshroud the countryside. Old growth trees and natural caves are both recurring themes in his work as places of exploration, as dens, portals to other realms, maws and tombs, making Keith’s eventual discovery of a coyote den not entirely surprising.

“In my heart of hearts,” says Barron, “I apprehend the natural world – at least the wilderness – as a supernatural realm. Supernatural in the sense that the wilderness of forest, sea and galactic gulf, is larger and more mysterious than we shall know in a million lifetimes stacked on end.”

There are tensions in They Remain, not only between man and nature and the supernatural, but also between those things and science. Keith and Jessica’s safe haven is a prefabricated module of plastic and metal, consisting of sleeping quarters and a shared laboratory – an outpost of human reason, but also a white geometric anomaly in a backwoods of green chaos.

“[The module was] my attempt to skew the story into a place where you aren’t quite sure if it’s science fiction or not,” say Gelatt. “I viewed the story to be all about unseen, conflicting forces in a state of tension – with two fragile people caught, or lost, between them, so I was trying to setup as many of those as I could. [You have] the natural versus the supernatural, but you also have technology versus the natural. You also have the company versus the individual. The past versus the present. The cult versus civilization. All of these, and others, are lurking in the background of what is, on its face, a very simple story about two people in the wilderness.”

“There’s often a tension between manmade constructs and the infinite planes that burn and freeze and unravel outside our grain of reality,” say Barron. “The module strongly inhabited my mind during the conception and execution of the story. Technically, its details aren’t crucial – I could’ve staged the couple in a hardback tent, bunker, ranger’s shack or a dozen other alternate structures. The module works on a couple levels – as a thin-shelled egg or cocoon plopped down in the wilderness, and it represents one of several nods to my influences – in this case, Carpenter’s The Thing, and Bass’ Phase IV.”

Of course, there is a much more obvious tension in the film: the one that twists in the relationship between Keith and Jessica. In the short story, the characters had a past romantic history, which puts them, isolated as they are, in a position of resentful antagonism. The characters are dialed up, their sexual dynamic foregrounded. “I wanted to deform and subvert the classic trope of people behaving badly while trapped in an isolated space,” says Barron. “I also took a hammer to the clichéd dynamic of couples who shriek at each other in ever escalating decibels like some kind of overwrought score.”

Gelatt had concerns about how Barron’s characterization would play on the screen, worrying that the portrayal of Jessica (and the entire film by extension) would read as misogynistic, that her actions would be easily dismissed as a stereotypical female craziness or that the whole thing was an elaborate revenge scheme and not supernatural at all.

“I didn’t want that at all. That’s the worst possible reading of this film,” says Gelatt. “I removed all reference to the characters having had a previous sexual/romantic relationship. We shot all that stuff, but I took it all out of the film because people who saw the rough cut where it was included reacted exactly how I did not want them to react. They got to the end of the film and said ‘Oh, so he left her and she’s getting her revenge. I get it.’ I hated that.

“My hope was that that interpretation would stand among other possible interpretations. But because it was the most explicit and obvious reason, people grabbed onto it.”

“In the end, Harper and Henderson (and Phil) made the choices and interpretations that suited their grasp of the characters and the situation,” says Barron. “My take is more sexually driven and full of innuendo. In my source material, the pair share a past that isn’t present in the film and Jessica’s motives, amplified by the genius loci of the site, are vengeful. The film takes the narrative in an icier, more science-fictional direction rather than dialing into horror/noir.”

Sex still plays a part, though, thanks to the horn.

The appearance of the horn cants They Remain irrevocably into the supernatural. It is too massive to have come from any animal of the natural world and Jessica’s initial explanation of where she found it is one of the most chilling moments in the film. It sits, a dark spiral, in the grass outside the camp module and exerts an obvious influence over the occupants, spurring on their libidos while warping time and space.

“The horn is basically the ultimate destabilizing element in the film,” says Gelatt. “Its appearance makes no sense. Its affect on them is hard to categorize, though clearly it makes them horny (pun somewhat intended). I had someone ask me recently if the horn was “real” in the fiction of the film. I don’t particularly like to answer those types of questions but in this case, I answered yes, most definitely. It might actually be the most real thing in the whole film.”

The presence of the horn drives the film to its enigmatic finale, pulling on all the rubber bands between natural and technology and humanity until they snap and a horribly wounded Keith climbs into a dark hole in the ground. The entire film depends on what happens in the few short minutes in that earthy darkness.

“I have a horrible habit of trying to land screenplays on the back of a single line of dialogue,” says Gelatt. “I tried it in Europa Report . . . And then I didn’t learn my lesson and ended up setting up the same kind of pressure on a single line of dialogue in They Remain. But there you go. “

“Knowing that I wanted [Jessica] to say something, my next thought was that she should say something that feels like it’s answering a question you, the viewer, weren’t necessarily asking. So that it would, hopefully, encourage you to go back and re-think the film, or wonder why that particular thing is thing she says to [Keith]. I wanted it to point both to his psychology and hers and to the wider, ominous world they’ve been existing in.

“On top of that, I really wanted the film to end with a question mark and darkness.”

And so it does.

* * *

The horn is actually one of a pair, both in the fiction of the movie and in the real world. They were made by Providence-based special effects artist Gage Prentiss out of foam core and sheathed in resin.

“They’re both still out there,” says Gelatt. “Laird can tell you where one of them is.”

“I received one half of the set as a gift from Phil and the team. It’s constructed of all-weather material and too large for an interior decoration, so I posted the horn on an ancient wicker chair near our driveway,” says Laird. “Most people give it the once-over and move on, but one delivery guy became a bit unnerved. He didn’t seem comforted by the explanation that it was a film prop.

“Maybe he thought that’s what they all say…”

They Remain is currently in limited theatrical release and will be available on Blu-ray and video-on-demand on May 29.

“—30—” is available in Laird Barron’s collection Occultation and Other Stories.

Barron’s debut crime novel, Blood Standard, will also see release on May 29. The first in a series about Isaiah Coleridge, an ex-contract killer looking to make a fresh start in New York state. Unfortunately, the disappearance of a teenage girl drags him into the darkness after her. A follow-up, The Black Mountain, is scheduled to appear in 2019.

Finally, a note of disclosure: Stu Horvath is friendly with both Phil and Laird. Both have previously been published in Unwinnable Monthly.

———

Stu Horvath is the editor in chief of Unwinnable. He reads a lot, drinks whiskey and spends his free time calling up demons. Follow him on Twitter @StuHorvath.