Signs & Portents

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #99. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

The Burnt Offering is where Stu Horvath thinks too much in public so he can live a quieter life in private.

———

Under a slate grey sky, there is a man standing in a flat field wearing a black cloak. His face is lowered as if in mourning, his features obscured. Two cups stand behind him, three lay before him, their contents spilled. In the distance, a ruin, a bridge and a river.

I am describing the Five of Cups from the Rider-Waite Tarot. The deck is perhaps the best example of a particular kind of art I have long been fascinated with – portentous, mysterious, that very explicitly says “This image is not what it depicts.”

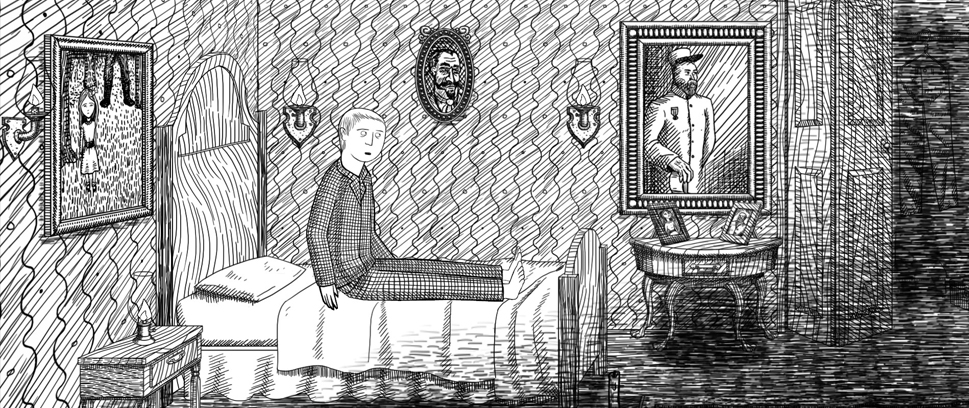

Developing a taxonomy for this sort of art is tricky, as there is not a lot of it. Mostly, I know it when I see it: Edward Gorey, Joseph Cornell, the Rusty Lake games, Christopher Manson’s Maze, the multimedia project Ceremony of Innocence based on Nick Bantock’s Griffin & Sabine books, certain illustrations in pick-your-path adventure books. In general, they tend toward flatness and are arranged to mimic the viewer’s point-of-view. Human figures, if they are there at all, seem carefully posed in strange positions rather than naturalistic – these are not portraits, but moments frozen in specific time, their gestures and expressions meaningful out of proportion. A fair amount of bric-a-brac, frequently including statuary, clutters the frame strange collections of objects that alone would be meaningless but together vibrate with importance. Distant ruins, monolithic structures, dramatic weather and moody landscapes complete the stage dressing. The mood is generally melancholy and often tinged with a looming sense of danger.

You might call it surreal, but I think a better word is occult, in its most literal sense. Hidden. Secret. It is no mistake that many of the examples I cite are games, where the viewer must suss out specific clues from a scene to progress a narrative. After all, what is the future depicted in a Tarot reading if not a puzzle?

Which brings us to Gorogoa, the beautifully illustrated puzzle game by Jason Roberts that, to my mind, has no equal.

Gorogoa is a bit difficult to describe. Think of it as a storybook that plays out in four adjacent panels. As you click on, arrange and stack those panels, you unlock secrets and the story proceeds. It may sound simple, but the illustrations, and the mechanics, manipulate space, time and scale in unexpected ways. The best way to understand the game is to play it.

As with the other artwork I mentioned, the imagery in Gorogoa constantly says, “What you see – a garden, a tower, a moth’s wing, a boy in a doorway, a cluttered room – is not what is.” Unlike many of those other examples, though, Gorogoa is not static. Through direct interaction with the art, you can sift through objects that radiate significance and find literal connections that offer not firm answers, but meaning. The result verges on the profound, offering a glimpse of something sublime and wholly beyond words.

To have devised a way to play with these images in a manner that doesn’t diminish their power is an accomplishment. To allow players to solve the mysteries the game holds without giving up their secrets is another thing altogether.

The more common meaning of occult is a mystical one. The occult sciences seek to peel back the veil of human understanding in order to witness the world that is not the world. To unlock the mysteries that lie behind and beneath the physical edifice of reality, a sorcerer employs symbols and ritual, finding sympathy between objects, motions and ideas. The revelations they bear witness to are as cryptic as the methods they use to reveal them.

Perhaps the simplest description of the hermetic arts is: to cause, through mundane actions, extraordinary effects. Lead into gold. Words into power.

When I play Gorogoa, the same is true. The world as I know it falls away. Archetypes swirl. Probability gives way to possibility. Natural laws disappear. I move the art. The art moves itself. This is ritual. This is magick.

———

Stu Horvath is the editor in chief of Unwinnable. He reads a lot, drinks whiskey and spends his free time calling up demons. Follow him on Twitter @StuHorvath.