Cuphead and the Racist Spectre of Fleischer Animation

Finding deeper meaning beneath the virtual surface.

———

Cuphead is a 2D platformer with run-and-gun gameplay reminiscent of classic games like Mega Man. What sets Cuphead apart from its predecessors is its unique aesthetic which pays stunning homage to early 20th century American animation. The artists at Studio MDHR, the Canadian company which developed the game, have done an impressive job recreating the dynamic rubber-hose character animation that producers like the Fleischers and Walt Disney made famous in the 1930s. By setting their game in this aesthetic, however, Studio MDHR also dredge up the bigotry and prejudice which had a strong influence on early animation.

When asked in a Rolling Stone interview about the unfortunate associations of Cuphead‘s 1930s aesthetic, lead inking artist for the game, Maja Moldenhauer replies: “It’s just visuals and that’s about it. Anything else happening in that era we’re not versed in it.” But these visuals are weighed down by the history that brought them into being, despite the developers best efforts at stripping them of the more overt caricatures that are rife in cartoons for most of the first half of the 20th century. By sanitizing its source material and presenting only the ostensibly inoffensive bits, Studio MDHR ignores the context and history of the aesthetic it so faithfully replicates. Playing as a black person, ever aware of the way we have historically been, and continue to be, depicted in all kinds of media, I don’t quite have that luxury. Instead, I see a game that’s haunted by ghosts; not those confined to its macabre boss fights, but the specter of black culture, appropriated first by the minstrel set then by the Fleischers, Disney and others -twisted into the caricatures that have helped define American cartoons for the better part of a century.

One of the first artists to make a name for himself with animation, James Stuart Blackton, would often animate in real time during vaudeville shows. In 1907 he produced his “Lightning-Sketches,” which involved converting the written word “Coon” into a minstrel caricature and “Cohen” into an anti-semitic stereotype. Vaudeville theater, which evolved out of the remnants of minstrel shows, often employed stereotypes and racist caricatures such as these for comedic effect. Many animators frequented vaudeville theaters after work, and were inspired by its methods.

The truth is racist stereotypes make for easy laughs (ask any faux-edgy comedian). And animation has always been a comedy-centric medium. In his book, Birth of an Industry, Nicholas Sammond writes:

“The stereotypical depiction… borrowing both from well-established graphic traditions and from minstrelsy, variety shows and vaudeville, also traded on an economy of efficiency in which characters immediately telegraphed their seemingly inherent natures and from that their place in the gag.”

Many early cartoon characters were tricksters, layabouts, and thieves, archetypes born from the depiction of the lazy slaves minstrel shows specialized in. Cuphead happens to star a pair of tricksters, Cuphead and Mugman, who make a deal with the devil over a gambling debt, an activity often linked in 1930s cartoons to the implied sinfulness and savagery of black Harlem and the era of swing music and jazz.

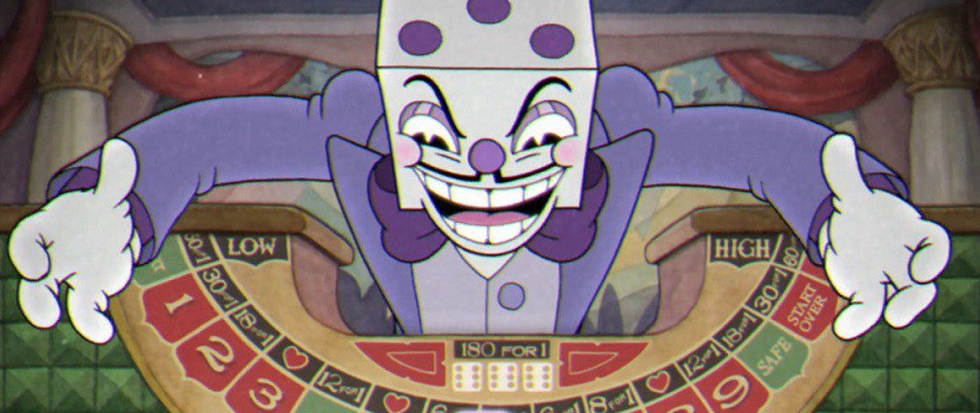

1930s Harlem and the jazz culture centered within it are a major part of Cuphead’s aesthetic, from its big band soundtrack to the design of characters like King Dice whose pencil thin mustache recalls the iconic look of Cab Calloway -himself a major player in early cartoons both as a cameo and as a caricature. Jazz culture tended to have a fraught relationship with the animation industry. According to Sammond: “…the jazz caricature of the early sound years seemed to pay homage to an imagined libidinous freedom of swing music and culture and to immediately offer up guilty punishment for taking pleasure in its apparent excesses.”

In a decade of increasing concern over morality – punctuated by the establishment of the Hays Code in 1930 – jazz, and Harlem culture in general, became synonymous with sin and a hellish afterlife. 1937’s Clean Pastures depicts black Harlemites uninterested in the heavenly hereafter due to the seductive sway of swing. The director of 1934’s Goin’ to Heaven on a Mule, Friz Freleng, sought to deliver a moral lesson specifically about a lazy, misbehaving black caricature, whose misdeeds resulted in getting him kicked out of heaven. In both cartoons, the all-black heaven is called “Pair-o-Dice” as a nod to the assumed connection between black culture and gambling. Judging by these “moral cartoons,” even heaven is a sinful place when populated by blacks.

So when Cuphead uses imagery of gambling, heaven and hell for its setting, it employs images and tropes that were established originally to make moral statements about the lazy and savage blacks of Harlem and their sinful “jungle music.” Calloway’s likeness may take the form of dice in Cuphead, but he is cast as a caricature in shorts like Clean Pastures and Swing Wedding -which depicts minstrel frogs who share a troubling visual proximity to the Ribby and Croaks boss characters in Cuphead.

By sidestepping this kind of over the top caricature, Cuphead attempts to represent the best of the jazz era’s relationship with cartoons. And there is a lot of good to be found. Calloway is an electric performer and cartoons like the Fleischer’s 1933 films The Old Man of the Mountain and Betty Boop in Snow White do far better justice to his inimitable style. At the same time, these examples feature his voice in the body of an old white man and a white-faced clown, respectively. When it comes time for cartoons to represent him as a human being, his lips balloon up, his eyes grow, and he is forced into the minstrel mold, the only way that animation studios seemed to be able to envision black characters for decades. That Cuphead follows the path of the Fleischers and hides what could have been his likeness behind an anthropomorphic talking dice is historically in line with black representation in animation. Once it became faux-pas to depict black characters as minstrels and racist caricatures, then the solution appears to be not depicting them at all.

This is essentially whitewashing: erasing the embarrassing parts of our past so that we can enjoy the good – the drums; the horns; the tap dancing; the big bands and their recognizable performers, along with the broad creative freedom of this style of animation – without having to ever think about the culture that generated this music in the first place; that was never allowed to own its own image.

The answer isn’t to flatten and purify the past, whose lessons many clearly still need. Instead of stripping the burnt black cork from the minstrel and presenting a clean white face, while still singing like Calloway or Armstrong or Waller, modern media that seeks to borrow from America’s conflicted past should do so in a way that reckons with what that past tells us about ourselves.

For example, Jay Z recently released a music video called The Story of O.J. in which he and the rest of the cast are animated in explicitly racist caricature, with big pale lips eclipsing dark faces. The video uses this striking visual imagery to accompany a song about the realities of being black in a world that still sees you as a stereotype (which makes Jay-Z’s own gross anti-Semitic stereotypes that much worse). Here, the caricature has a purpose, which is to remind us of our history; to proclaim that it isn’t behind us, and that we can’t, as O.J. tried, truly ever shed our skin color.

Similarly, the artist Kara Walker, uses a cutout style to create giant tableaus featuring mammies, sambos and other black caricatures to engage in the “…the meaty, unresolved, mucky blood lust of talking about race…” as she tells Vulture in an interview. What is made evident by her art, is that race is not a solved matter, not a period in our past that we, as a society, can claim to have solved. Most black Americans cannot help but recognize this depressing fact, and the events of the past year have made it hard for anyone but hardcore bigots to ignore.

The images in Walker’s work and in The Story of O.J. are meant to provoke, to pick at a wound that has never truly healed. But Cuphead is just supposed to be a fun game; and it is -beautiful too. Yet playing it brings along that particular queasiness one gets when being forced to ignore problematic parts of media in order to enjoy it. After all, it’s difficult to enjoy the same images that brought down houses I would never have been allowed to enter. It’s hard to overlook a style that was also used to belittle and stigmatize blackness to the extent that we are still fighting to regain our own image. As Samantha Blackmon writes in her excellent piece on the subject: “My life, my experiences, and the body that I live in makes Cuphead and its artistic style problematic to me because of all that it has come to mean in the last 85 years or so…”

It’s a mistake to whitewash history, not if we hope to improve upon the present. After all, the animation industry is still so white that a roundtable about diversity last year had only white men on it. The videogame industry is no better. It’s difficult to argue against the idea that this lack of diversity winds up having a strong effect on the kinds of stories that get told, and the sort of aesthetics and time periods studios feel comfortable borrowing from in the first place.

After World War II, when the NAACP and other organizations ran campaigns criticizing explicitly racist caricatures in animation, the industry responded by simply ceasing to create black characters of any kind. In Christopher P. Lehman’s The Colored Cartoon he writes: “No theatrical cartoon studio created an alternative black image to the servile, crude, hyperactive clowns of the preceding half-century. The cartoon directors of the 1950s, many with animation careers dating back to the 1920s, had no experience in developing such a figure.” Studio MDHR, in interviews, is quick to point out that they avoided stereotypes in Cuphead; that they focused on “the technical, artistic merit, while leaving all the garbage behind.” The truth may be dirty, and often uncomfortable. But it’s preferable to offering up a bleached white past, while pretending nothing was lost in the process.