On The Case of the Bloody Iris

Giallo film was a cycle of Italian murder-mysteries that flourished for a few decades in the mid-20th century. Giallology is a humble appreciation of these movies.

—

The past five films we’ve talked about have all been from 1971. The Case of the Bloody Iris—or translated from the Italian title, Why Those Strange Drops of Blood on Jennifer’s Body?—moves us into 1972. Fret not: we will probably be back to ‘71, since during the yearlong frenzy in the immediate wake of Dario Argento’s 1970 The Bird With the Crystal Plumage, over 30 gialli were produced.

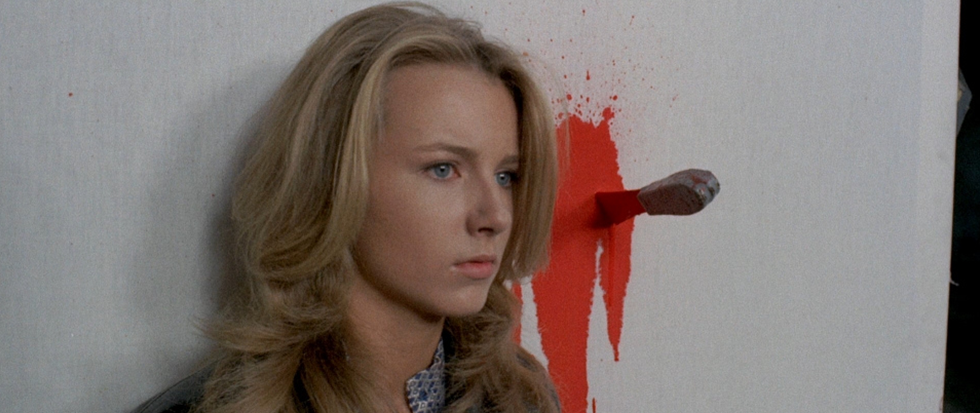

The Case of the Bloody Iris is a solid, competent example of the genre, much like Paolo Cavara’s The Black Belly of the Tarantula—with which it shares the killer’s distinctive thick beige rubber gloves. Director Giuliano Carnimeo is better known for his Spaghetti Westerns, including the delightfully titled Sartana series (see Have a Good Funeral, My Friend… Sartana Will Pay). For Bloody Iris, his only giallo, he teamed with prolific screenwriter Ernesto Gastaldi (also of Death Walks on High Heels and numerous other giallo), regular Jess Franco composer Bruno Nicolai, and a cast that features Edwige Fenech and George Hilton … the exact two leads found in another 1972 giallo, Sergio Martino’s All the Colors of the Dark. Whew!

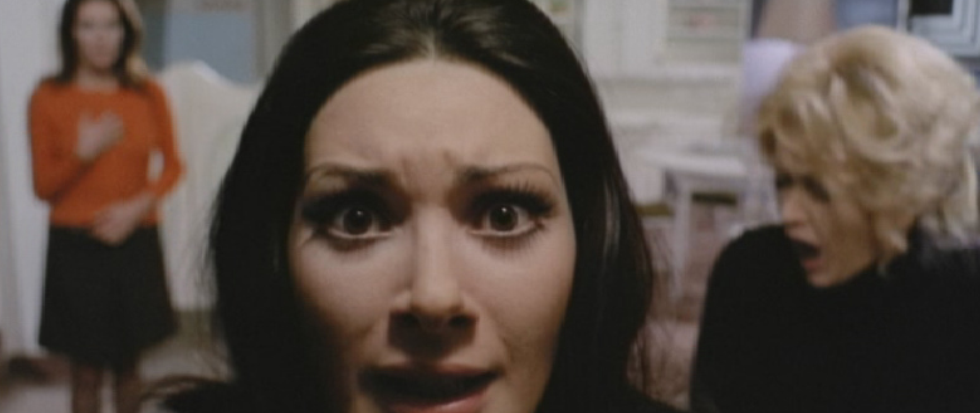

Fenech is one of the most iconic giallo actresses; she’s gorgeous, obviously, but there’s something about her thin eyebrows and eternally on-point eyeliner that screams glamour, the kind of glamour perfect for a genre where every woman is either a model or an heiress. It is for this reason that it pains me to report that The Case of the Bloody Iris puts Fenech in some truly hideous outfits. We get a lot of grim orange-and-dark-green palettes and one standout that I can only describe as “the school uniforms from Cardcaptor Sakura but also a nun.”

Gastaldi’s script is full of oddball touches, both large and small: the entire movie takes place in and around a single apartment building; two separate murders happen in broad daylight without anyone around noticing anything for an absurdly long time; Fenech has a stalker ex-boyfriend who just wants her to come back to his manipulative free-love sex cult, which somehow doesn’t figure into the plot; George Hilton confesses early on that the sight of blood makes him sick, which is of course explained in the climax—but not in a way that has any bearing on what happens at all. It’s just there to be explained.

Cinematographer Stelvio Massi gives the film a nervy energy (one missing from its slapdash English dub), adeptly handling deep shadowy suspense scenes to glimmering overheated John Boorman-style lighting. He frequently leans on handheld POV shots with a wide-angle lens—not quite fisheye, but wide enough to feel queasy—and shaky handheld push-ins instead of to cutting to a point of interest. Between Massi and Bruno Nicolai’s swinging score, the film has a pop texture; it is about the fashion world while looking like a product of that world.

But it’s darker than that, underneath. Fenech and her roommate Marilyn (Paola Quattrini) pose for a bitchy gay stereotype’s camera and dancer Mizar (Carla Brait), the only black woman in the film, is salivated over like a prize—something made explicit when Fenech’s ex, in the midst of beating her in her own home, yells “You are an object and you belong to me.”’

He bluntly cuts to the heart of gender relations in the giallo(1). Men see sex as their right and the moment it is denied they respond with violence. The world bends to normalize that violence; even the police, ostensibly working to protect victims, say things like “Every man wants a black girl.” When the killer reveals himself, saying he killed all these women because they “corrupted” his daughter, it’s really no surprise. He sees his daughter as a possession (when he says “corrupted” you can be sure he means “she was a lesbian”), and sexual autonomy as the basest moral depravity.

The Case of the Bloody Iris doesn’t interrogate this material as deeply as the best giallo, but it has enough messiness to warrant digging into; queer women in giallo is a topic worthy of its own column! And, as much as I love these movies, when considering how painful they can be when they lack energy the verve on display here is much appreciated.

1 As ever I have to note that relationship is largely binary, with trans and gender nonconforming people only appearing as punchlines (Argento’s 1982 Tenebre being one exception) if they are even distinguishable from “drag”/all-purpose Gay Stereotype characters … but this is not endemic to giallo by any stretch of the imagination.