Nour: Food Art Made Playable

Nour is making players hungry. The game’s Kickstarter calls it “an interactive food sim” unlimited by objectives or social mores, leaving players to manipulate the physics of deliciously rendered meals to their heart’s content.

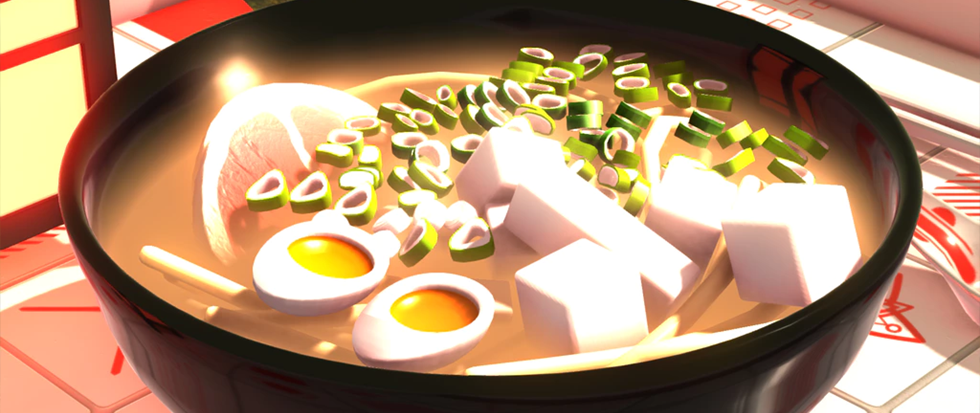

But the more the player interacts with their food, the more the combination of color, sound, and design seems to transpose the experience into a form of performative art, with dishes like avocado toast, ramen, and bubble tea transforming into instruments played by your keyboard (or Midi Fighter, if you so prefer).

This intersection of food and art isn’t new; the two have a rich history together, though not in video games. Few developers that have touched the subject of food, and those that have trended towards gamifying cooking, whether through focusing on its cooperative aspects (Overcooked) or by attempting simulation (the Cooking Mama series). Many games may include edibles as a source of health, but outside of the inventory food has little role to play in the subject material.

Creation By Jennifer Rubell : Performa 09

© Kevin Tachman 2010

With contemporary art, however, it is a different story.

In the 20th century, as the middle class became further and further detached from how their food got to their plates, the subject began to take on new symbolism for artists. This led to the creation of some of contemporary arts’ most-renowned works, ones I’m sure anyone who has sat through an art history 101 class would recognize; pieces like Andy Warhol’s “Campbell’s Soup Cans” (1962) and Roy Lichtenstein’s “Still Life with Crystal Bowl” (1973), that critiqued consumerist economies and mourned a loss of individuality at an otherwise intimate setting: the dinner table.

But while expressionists and pop artists portrayed food as a commentary on substance, a branching movement shed this cynicism in favor of capturing the fleeting nature of food itself.

Art by Daniel Spoerri

With the rise of the Eat Art movement in the late 1960s, food would become a medium in itself, taking its place alongside the artist’s pen, pencil, and paintbrush. The movement is considered by many to have its roots in Daniel Spoerri’s “snare pictures,” pieces of nouveau realism in which he would display leftover scraps and silverware from meals affixed to a table or plank. His most famous, “Eaten by Marcel Duchamp” (1964), immortalizes a meal Spoerri shared with the famous pioneer of Dada art. Spoerri would further challenge the traditional definition of aesthetics with galleries that included fully operating restaurants where patrons enjoyed elaborate meals and table service from art critics.

Other creatives expanded on these ideas. Brazilian artist and photographer Vik Muniz grew famous in the latter half of the 20th century for his paintings in chocolate, caviar, and sugar, each medium a commentary on the subject depicted. The annual performances of Jennifer Rubell, a former food writer, would become some of the industry’s most publicized events. On example: her biblical-themed exhibition “Creation” (2009) featured a literal ton of barbecued ribs drizzled in honey from a ceiling mount. Many artists took the concept of a shared meal, with its increasing scarcity in daily life, as art to be celebrated, such as Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija, whose performances involve him constructing meals on stage that feed his audience.

This narrowing of the creative space between artist and viewer – in some cases the actual breaking of bread between the two – blends further when one considers the most popular conduit through which we consume food art: Instagram.

In 2015, there were 178 million photos tagged #food on the app according to Wired, and another 56 million tagged #foodporn. Not every image may have been posted for artistic reasons, but as Spoerri and his proponents prove, modern art bucks traditional definitions of the medium. And while opinions may be mixed about the mermaid, unicorn, and rainbow colored dishes dominating our screens, one thing can’t be denied: they aim to get a response. Preferably, a like.

With how much preparation and choreography goes into a single snapshot, it’s easy to draw parallels to performative art – even if one’s followers are the only ones watching. Recently culinary schools have even begun to offer classes teaching chefs how to create Instagram-worthy dishes. Companies, too, are rushing to contribute their own versions of popular favorites to cash in on trends (ironic, when you think back to the message behind Warhol’s soup cans).

Nour’s style mimics these Instagramable color motifs in many ways with its sugary soft pastel palette and stark visuals. But it encourages viewers to go one step further than a like button. Nour’s, developer, Hughes, asks players to join him at the reins to elevate his artwork into an experience, much in the same way Spoerri and countless other creatives have done before. And in doing so, he sends a clear message: good food is a universal concept.

Developed by Terrifying Jellyfish, Nour is currently being funded on Kickstarter.