A Softer West Part 2 – Trigun

This article is a continuation of last weeks Trigun article, which you can read here.

Trigun fancies itself a story about communication, about empathy, a story about how violence and exploitation are mostly a matter of misunderstanding or narcissism, how revenge is ultimately unjust and how no situation is so hopeless it cannot be resolved in everyone’s favor; in many ways it’s almost a deconstruction of the Western genre. The resolution of the story comes not after a major gunfight between Vash and Knives – in fact, Vash’s one major loss in the story comes when he is forced to take a life – but when it’s revealed that all of Vash’s wondering over the last 100 years has given him a perspective and a knowledge that lets him bridge the gap between human beings and the species of living power-plants he and Knives number among.

Vash may be a gunslinger but he’s not a killer, and if he had his druthers he’d rather not fire a shot; this is a man who will stop in the middle of a gunfight to tourniquet his enemy’s wound should it be too severe, after all. And though Vash’s travelling companion, the homicidal priest Wolfwood, tries more than once to teach Vash that mortal violence is not only occasionally useful but necessary, the story bends over backwards to show that Vash is in the right. Even when Vash is finally forced to kill, the significance of this act is lost in the bustle and noise of the plot so that one forgives him almost out of convenience. There’s some lip service paid to absolving him that fits nicely into the theme of community and family the series has been building, but it seems trite given that this comes after hundreds of pages of fetishized violence, of gunfights so intense and so drawn out and absolutely bizarre that it’s hard to imagine Nightow was wringing his hands over his any possible contradictions.

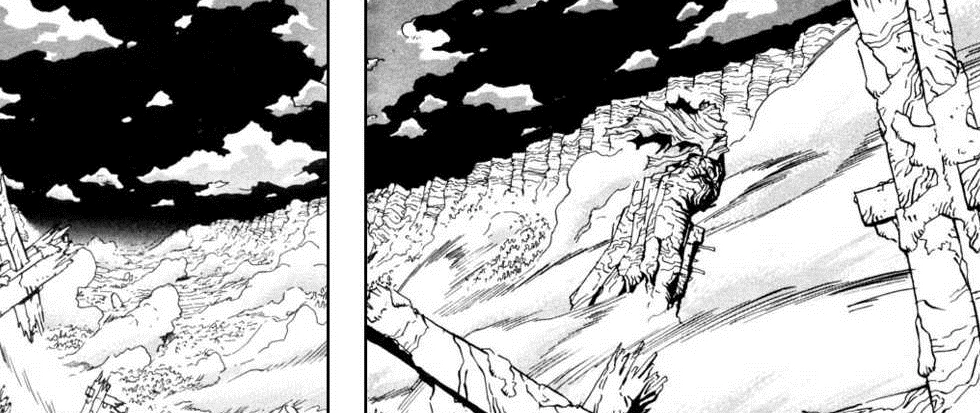

They’re alive, these fights, and move with a manic, lightning-fast energy that would be balletic in its choreography if not for the fact that it’s simply too unrestrained to be described by a word lousy with associations of refinement and formality. They are fun and they are spectacle and while that’s perfectly appropriate for the art style, it’s absolutely antithetical to the often grim atmosphere and the pacifistic preaching that is the series’ major pretension. It’s difficult to walk away from the gleeful gore of Livio and Elindira’s final match and the bombast of Legato and Vash’s fight into the finale without detecting a strong whiff of hypocrisy: Nightow may say he’s a pacifist but his actions betray him as someone with a fetish for violence.

Which is fine. One just wishes Nightow had realized this before he went and crippled his own series by pursuing an ideological agenda he is essentially uncommitted to. Instead, though, he spends hundreds of pages on side-stories that help develop the setting and Vash’s philosophy and his character through his interactions with a supporting cast that might be visually compelling but offer nothing for our hero to play off of and no new sites to excite. There is a moment at the end of volume 5 where the entire series seems to be coming to a head: after two volumes of intense fighting between Wolfwood and Vash on one side and a pair of assassins on the other, everything goes absolutely ballistic. Vash loses control of his supernatural powers and threatens to go nuclear, an accident that carries a number of revelations about Vash’s spottily explained past; Midvalley and Hoppered, the last of the known Gung-Ho Guns, mount a desperate coup against Vash’s brother Knives that ends in failure; Legato, Knives’ right-hand-man, shows himself in person for the first time since a major time-skip; the “hidden” Gung-Ho Gun Elindira the Crimson Nail is introduced with much fan fair; it’s confirmed that rescue ships are on their way from earth; Knives hovers overhead in his mobile fortress and….and then?

And then the wait. Though Vash will eventually be kidnapped by Knives under similar circumstances, though this is the perfect opportunity to introduce the final three Gung-Ho Guns now that the ranks have been cleared and, in doing so, reveal Wolfwood’s game-changing connection to them, Nightow decides instead that Elindira and Legato should flee for completely unspecified reasons so that the cast can stumble through interchangeable desert villages for the next two volumes and so he can flash-back to Vash’s past for an unnecessary round of exposition. Nothing that happens in these two volumes is essential for advancing the plot or the characters. All this delay seems to do is squander the freight-train levels of momentum Nightow had built up until this point for a few cheap diversions that serve only to develop a banal theme. This is a series that works at its best when it runs, when it moves; Nightow does  not do well when allowed to sit still and philosophize. Nothing betrays him here so completely as his dialogue, which is by turns stilted, inane and, at its worst, absolutely incomprehensible and, in not uncommon cases, all three. Not that battles are free from this nonsense, either: “Breaking through all strategy and technique, your only gift is the blessing of the gods of battle. Yet you press on, inch by inch, you devil. Yet that is exactly why you are darkness under another name… don’t make a sound, Chapel!” the Gung-ho Gun Midvalley mutters at some point, saying absolutely nothing in the most needlessly cryptic way possible. At one point Vash’s drinking buddies decide to give him a round of advice, but what they really meant to say is anyone’s guess. “Time is what’ll save you,” one of them suggests. “You’ll end up all alone, but you’ve always been alone. And for times like that there’s music and (liquor). You’re expecting too much. Remember, you didn’t get any gifts when you were born into this world.”

not do well when allowed to sit still and philosophize. Nothing betrays him here so completely as his dialogue, which is by turns stilted, inane and, at its worst, absolutely incomprehensible and, in not uncommon cases, all three. Not that battles are free from this nonsense, either: “Breaking through all strategy and technique, your only gift is the blessing of the gods of battle. Yet you press on, inch by inch, you devil. Yet that is exactly why you are darkness under another name… don’t make a sound, Chapel!” the Gung-ho Gun Midvalley mutters at some point, saying absolutely nothing in the most needlessly cryptic way possible. At one point Vash’s drinking buddies decide to give him a round of advice, but what they really meant to say is anyone’s guess. “Time is what’ll save you,” one of them suggests. “You’ll end up all alone, but you’ve always been alone. And for times like that there’s music and (liquor). You’re expecting too much. Remember, you didn’t get any gifts when you were born into this world.”

It’s not just awkward because none of the dialogue flows logically but also because it sounds like one half of a conversation the other half of which we’ll never hear. Is this man comforting Vash because of his reputation, telling him that he’ll be fine because he’ll be forgotten in time? Alright, then why the last addendum about “expecting too much?” How does he realize that Vash has spent so much of the series battling his own loneliness? He’s said nothing of the sort to the man. There will never be a clear answer because there’s no clear exchange here: it’s absolutely impossible to determine what, exactly, he’s responding to when he says all of this. This kind of elliptical conversation is not uncommon in the series and renders many of the pivotal scenes unintentionally hilarious. If the glamorized violence didn’t render the themes absurd by hypocrisy then the hamfisted delivery of these so-called insights absolutely does. It’s a bit silly that the comic writer and critic Jason Thompson once claimed that Trigun, while attempting to combine the best of both manga and American superhero comics, managed to avoid “the terrible pacing and excessive text” that plagues American comics when in fact Trigun’s most glaring flaws are its erratic pacing and pretentious, wordy dialogue.

It’s not that Trigun is bad comics. It’s not even that it’s mediocre. At its best it shows a truly inspired artist doing things with action sequences that have rarely been done before. It’s simply a deeply confused story that was in serious need of an editor. Does it want to be a deeply ugly Western that explores the nature of violence and survival? A deconstruction of the genre that posits the old fascinations with violence are just a juvenile resolution to disagreement? A slap-stick cartoon? Or just a damn fun excuse to watch the bullets fly and carnage pile up? It’s not that it’s impossible to combine all of these elements at once, but it takes far more skill and sophistication and a good deal more self-awareness than Yasuhiro Nightow had when he tackled the series. Because of this, Trigun missed its chance to be one of the finest action comic of all time and instead ended up a very fun but deeply clumsy and trite Western marred as much by its self-defeating pacing as by its self-confounding thematic concerns.