LGBT Stories Come in More Shades than White

Between 2013 and 2015, queer representation in video games skyrocketed. The number of annual releases with queer content doubled in that time period, according to a study by Queerly Represent Me presented at the 2017 Digital Games Research Association. As to the cause, the organization cited an increasing coverage of LGBT creators and players in the burgeoning Gaymer community, which would host its first convention in 2013 – one of many that year focused on representation in the industry. Additionally, a proliferation of free development tools (Twine, Unity) combined with popular distribution options like itch.io and Steam felled traditional entry barriers for the industry, creating a platform for stories from and about marginalized groups.

But with all these new queer video game characters flooding in, few have stopped to ask a very important question: Why are almost all of them white?

Certain genres now include an impressive array of LGBT and ethnically diverse side characters, and many RPGs allow players to customize their appearance and romance multiple genders, but these aren’t stories about being a queer person of color. These are side plots, skins, diversity that players can opt out of given their choices in-game. Few games allow you to play as canonically queer people of color and experience their stories.

Indie developer Brianna Lei wanted to correct that in her pay-as-you-want visual novel, Butterfly Soup. A Chinese American, she grew inspired to create her own game after having grown up seeing few people that looked like her in media. The few Asian American characters she did find rarely interacted with other minorities, the opposite of her childhood experience in San Francisco. “Having such a big aspect of my daily life missing from those stories made them feel unrealistic and fake,” Lei said. In Butterfly Soup, these very relationships would take center stage.

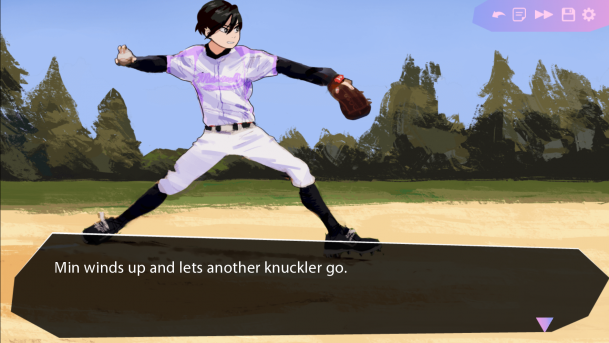

In each of the game’s four acts, players assume the role of one of its four main characters: Diya, a soft-spoken but physically intimidating athlete; Noelle, ribbed as the stereotypical Asian student by her friends, though with a prankster streak; Akarsha, the off-beat comic relief of the bunch who’s got all the vintage memes; and Min-Seo, whom Lei described as “tiny but hyper aggressive.” Apt too, considering she threatens to maim nearly every character in the game.

The game switches between its present day, 2008, and flashbacks to when the girls were in elementary school. There we see Min-Seo’s affection for Diya blossom as Min-Seo struggles with her gender identity and the rigid feminine stereotypes her parents expect her to maintain. Seeing Diya’s prowess at baseball despite being the only girl on the team leaves her in awe. The two quickly become friends and, after learning she’ll be moving away soon, Min-Seo makes Diya promise that they’ll both become skilled baseball players and be on the same team someday.

Flash-forwarding to high school, Diya’s extreme shyness makes keeping this promise difficult as her school unveils its new baseball team. With her friends Noelle and Akarsha at her side, she’s able to overcome her anxiety and attend practice, only to discover that a previously rumored delinquent transfer student is none other than Min-Seo. The four bond over the game, and that friendship grows when Akarsha and Noelle conspire to help Min-Seo finally ask her childhood crush out on a date.

The cast of Butterfly Soup includes a wide range of minorities, many with specific ethnicities that are referenced throughout the game. Diya and Akarsha are Indian, Min-Seo and her twin are Korean, Noelle is Taiwanese, side characters are black, Pakistani, Filipino; the list goes on and on. There are so few white people in their community, similar to Lei’s own growing up, that Min-Seo and her brother express doubt when a white friend correctly states that Asian Americans only make up four percent of the country.

“A few times making Butterfly Soup,” Lei said, “I actually thought, ‘Is it realistic for that mix of people to be friends?’ even though my childhood was literally like that, in real life. It’s crazy how not seeing it in media can mess with your head.”

While the characters relationships aren’t defined by their ethnicities, they often bond over things that many white characters wouldn’t have the same exposure to. Diya and Min-Seo share aspects of their culture with one another, teaching each other their language (though, of course, Min-Seo takes advantage of this to get Diya to say “I love you” in Korean). Min-Seo and Noelle overcome their initial animosity towards one another when they trade stories about how their strict parents expect each of them to conform to traditional Asian values and gender roles. In a similar way, Diya, doesn’t consider talking to her parents when she begins to question her sexuality.

“I think a lot of Asian American kids feel a huge gulf between themselves and their parents,” Lei said. These kinds of generational gaps, which can often include cultural and language barriers, lead many children and teens to fill that void with close friendships.

Several popular games about LGBT characters explore similar themes of isolation and familial disconnect, but they do so almost exclusively through a white perspective, ignoring factors at play that may be unique to minorities. Examples of this are peppered throughout Butterfly Soup. Characters casually mention racist taunts, they comment on the number of white people and ignore insulting catcalls while they walk down the street. These moments are brief, but piercing, and reminders of the importance of playing as characters from diverse backgrounds.

While Triple-A studios may be lagging behind on this front, several other indie studios and developers have stepped up to bat (you know there had to be at least one baseball pun). Twine and Choice of Games, with their simplified take on coding, have become hubs of diverse stories. Meanwhile, popular titles like Technobabylon by Wadjet Eye Games and Oxenfree by Night School Studio have proven that stories of queer characters of color can be appealing to more mainstream audiences.