Unemotional Investments – My Lesbian Experience with Loneliness

It’s not surprising that Nagata Kabi’s My Lesbian Experience with Loneliness has been so well received in America. Alongside Fantagraphics’ Massive anthology and Gengoroh Tagame’s My Brother’s Husband, it is one of the few manga about homosexual experiences in Japan translated for American audiences that does not slot easily into the more sanitized yuri and yaoi genres; of these it is the only memoir, and the only work to focus exclusively on the lesbian experience. That it provides a rare glimpse into a marginalized lifestyle in a society known for persecuting many of its minority citizens by treating them as invisible would have brought it attention enough; that it is also an unsparing, frequently look at the author’s incredibly messy sexual awakening guarantees its acclaim.

Yes, American audiences have seen their own share of bold treatments of lesbian experiences in Alison Bechdale’s Fun Home and its legion of imitations, but even at their most candid these works tend to tackle the subject with an urbane sophistication that cordons them off as something respectable, as something self-consciously artistic. None seem so frantic as Kabi’s work. So desperate. How else to describe the way Nabi subjects herself and her emotions to a scrutiny that might feel exploitative if it was handled by an author less sensitive or any author more sensational? There hardly seems a more fitting word for Nabi’s confession that in the worst moments of her binge eating she would chew on uncooked ramen noodles until they were coated in blood. Or the panel where she gropes her own mother’s breasts to act out feelings she’s not even begun to understand. No element of her sexual awakening is spared a thorough plumbing, nor are the attendant (and in some cases causal) feelings of depression, alienation and self-hate given short shrift.

mother’s breasts to act out feelings she’s not even begun to understand. No element of her sexual awakening is spared a thorough plumbing, nor are the attendant (and in some cases causal) feelings of depression, alienation and self-hate given short shrift.

At the best of times this leads to the book’s most interesting explorations of the subject of sexuality, allows Nabi to offer reader’s something beyond the familiar personal arc of a girl hiding her true feelings from a hostile world. Her revelation isn’t a foregone conclusion: in fact, it is not until much later in life that she even begins to see how her sexual feelings have been so tangled up with her own ideas of self-worth, family propriety and passions for so long that she could not have understood them without thorough investigation. The first half of the book deals almost entirely with feelings that spring up after the salad days of her highschool years give way to a shapeless dread and personal dissolution she can barely name or give thought to. It is only slowly, over years of self-reflection and an awakening that springs from success as a manga artist (a road she also takes in seeking acceptance), that Nabi begins to understand that so much of her unhappiness is wrapped up in self-abnegation, a self-abnegation that turned into an outright fear of sex and intimacy.

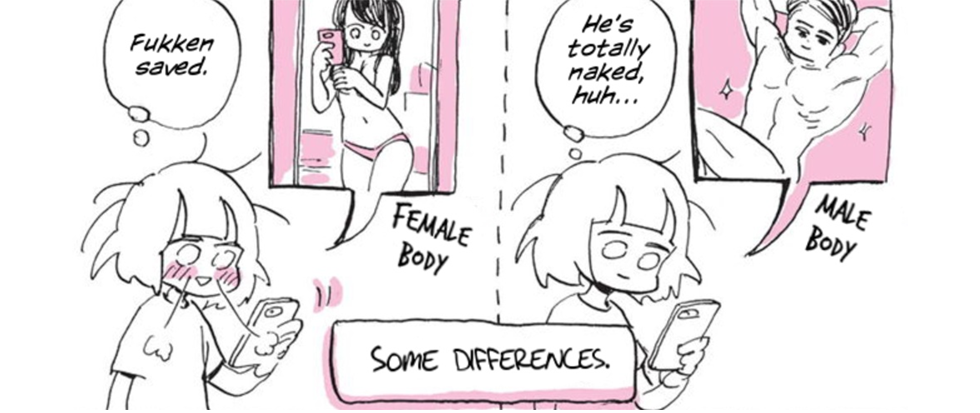

For as unsparing as she is in presenting the minutiae of her life and her feelings, though, Nabi has also constructed a kind of formal shell that prevents her and reader both from actually engaging with the most bracing elements of her story. Everything is analyzed, yes, and no emotion unexamined, but almost nothing is dramatized: whether she’s recounting her climactic (or anti-climactic, as is the literal case here) encounter with an escort or an inspiring job interview, Nabi does not let the events play out as  they were. She cannot help but break-up the flow of events with page after page of panels explaining her feelings with abstract asides that renders them inert, cannot help but subjecting them to narration and interpretation that mediates our reading of the experiences. A tactic which reduces even the most distressing of these events emotionally safe. How could one feel the discomfort that arises at her first physical contact when she’s busy explaining sex as a communicative act with panel after panel of loaded metaphors about playing baseball and opening treasure chests?

they were. She cannot help but break-up the flow of events with page after page of panels explaining her feelings with abstract asides that renders them inert, cannot help but subjecting them to narration and interpretation that mediates our reading of the experiences. A tactic which reduces even the most distressing of these events emotionally safe. How could one feel the discomfort that arises at her first physical contact when she’s busy explaining sex as a communicative act with panel after panel of loaded metaphors about playing baseball and opening treasure chests?

This may accurately reflect her own mental state given how self-conscious and analytical she seems at every moment in her life, but in a story this personal such a telling renders all but the most visceral of her experiences dry. Those events I reacted strongly to were only on account of my own personal experiences with depression and isolation; experiences and feelings I was familiar with only by dent of association with friends and family I could empathize with but never feel. Experiences I had no close analogue for I could understand yet not even empathize with.

It’s not that she’s fallen prey to a need to over intellectualize her life as her aforementioned American counterparts have. Her explorations are too sincere, too revealing for that. She is not intentionally shying away or circling around these subjects. Rather, she seems not to understand that some elements of the human experience lie beyond our ability to convey with simple prose. It’s as if she misses that art should sometimes come at us by surprise, sometimes should elude our ability to make easy sense of. Though at rare moments – moments of insight or emotional liberation – she allows herself to express these feelings more fully by opening up the constrained four-panel grid that has structured every page for a slightly more spacious three-panel construction, even these efforts feel constrained: after all, the change is nominal. She is only just brave enough to bust open a self-imposed formal restriction. Though Nabi’s learned there is no disconnect between one’s mind and one’s body, she hasn’t yet grasped that there is no disconnect between art’s form and its effects, or just how art conveys experience. Lessons she should learn if she wants to realize the promise of this flawed but interesting hit.

constrained four-panel grid that has structured every page for a slightly more spacious three-panel construction, even these efforts feel constrained: after all, the change is nominal. She is only just brave enough to bust open a self-imposed formal restriction. Though Nabi’s learned there is no disconnect between one’s mind and one’s body, she hasn’t yet grasped that there is no disconnect between art’s form and its effects, or just how art conveys experience. Lessons she should learn if she wants to realize the promise of this flawed but interesting hit.