On A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin

Giallo film was a cycle of Italian murder-mysteries that flourished for a few decades in the mid-20th century. Giallology is a humble appreciation of these movies.

—-

Lucio Fulci is best-known for the trio of gore-soaked zombie movies he directed starting with 1979’s Zombi 2, but his career overall was typically eclectic, from westerns and comedies to poliziotteschi and adaptations of White Fang.

I don’t know what your typical cinephile knows about Fulci, or where he sits in the critical canon—so thank god that’s not why you’re here! All I can say is that of the biggest names to work in giallo, among Dario Argento, Mario Bava, and Sergio Martino, Fulci has always held a strange, elusive allure for me. Maybe it’s because I went about things backwards: spent my youth mainlining “extreme” cinema and gradually filled out my understanding from there, meaning I started with Fulci’s most disreputable gut-munching work and found myself surprised at the acuity and verve of his thrillers.

A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin is a fascinating, hallucinatory giallo that finds Fulci firing on all cylinders. He manages to blend post-Antonioni slipperiness with overt surrealist gestures, within an overarching murder mystery whose procedural elements are legitimately twisty and interesting. Cutting back to the cops in this movie never feels rote or like Fulci’s marking time. They even get some good lines.

Acidemic’s Erich Kuersten, writing about Fulci’s 1981 House by the Cemetery, explains the Antonioni connection by saying “no one genre or storyline settles over the suspicion and enigmatic movement to become ‘predictable.’” Argento’s giallo bear this same characteristic: their very nature seems elusive, although an obsession with seeing, photographing, witnessing dominates them. Disparate plot elements from various genres are casually woven together, and there’s never a definitive “oh, it’s a horror movie” moment. This is what links, for example, Olivier Assayas’s brilliant Personal Shopper to Fulci’s The Psychic or Argento’s Deep Red: a willingness to dance among signifiers, never letting the audience get ahead of you.

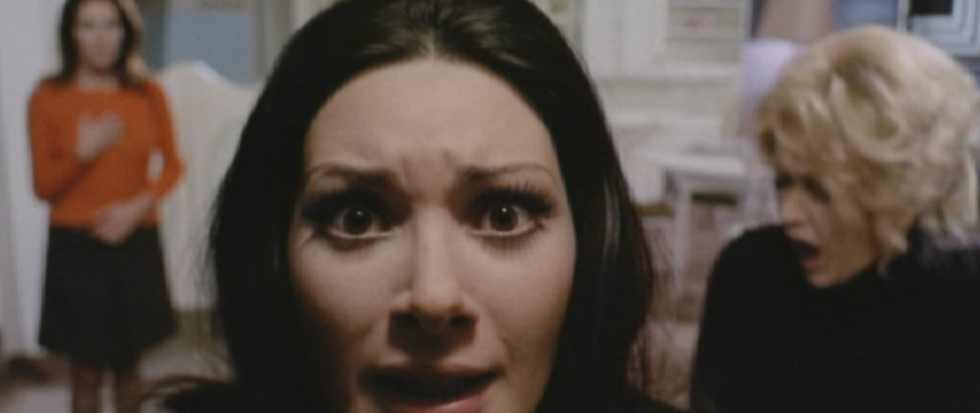

Fulci’s screenplay, co-written with three other writers including recurring collaborator Roberto Gianviti, opens with a claustrophobic, jump-cut nightmare of sexual terror. Carol (Florinda Bolkan) makes her way first through a packed train and then a bizarre, endless hallway full of naked revelers. Then she falls into a room devoid of light—velvet blackness all around, save for a lurid, red mattress on the floor and the mocking, nude Julia (Anita Strindberg). Ennio Morricone’s (hello again Ennio!) score implies a tenderness toward Julia from Carol, breaking from Goblin-style bass-led jazz riffing to a delicate piano and vocal piece.

DP Luigi Kuveiller (Deep Red)’s camera, which captures the nightmare with hyperreal clarity, turns gauzy as Fulci crosscuts to Carol stirring awake in her bed. So far, so repressed. As Carol talks with her psychiatrist, Dr. Kerr (George Rigaud), the subtext of the dream is laid bare: Julia, in real life a sort of debauched hippie goddess who lives next door to Carol, represents “moral degradation.” The dream is an internal struggle among the various parts of Carol’s psyche.

There are few things in cinema less interesting than on-screen therapy sessions. They offer an easy way for writers to explain psychological dynamics in baldly obvious terms. But the blunt imagery of Carol’s dream plus the dry exposition of Dr. Kerr are quickly undercut by another dream, this time of murder.

Carol imagines herself murdering Julia, and wouldn’t you know it—Julia turns up dead in real life, the details of the murder suspiciously close to Carol’s dream. It’s a massive credit to the craftsmanship of A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin that it ever plausibly makes the viewer doubt Carol’s culpability given this device. I’ve seen this movie before and I still wasn’t sure how it all shook out.

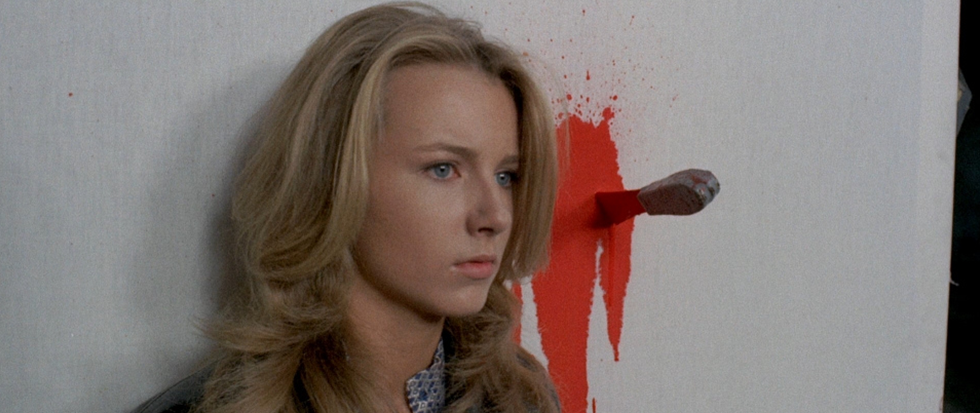

“It’s a positive removal of a mental block,” Dr. Kerr rhapsodizes about the direction of Carol’s dreams. No one seems to care much about the real-life Julia, the actual person who is killed. The cops called to the scene grumble about having to work a murder on Saturday, and one of the higher-ups opines that he’s “not surprised” that Julia was stabbed to death, due to her lifestyle. Julia remains a cipher, relayed to the audience through secondhand judgement and brief flickers of flashback. Early on, Fulci juxtaposes one of Julia’s acid rock ragers with Carol’s family quietly eating dinner; Julia has the glassy, dispassionate eyes of a vampire countess who has long outlived the pleasure of hedonism, leaving only the act.

There’s a direct line to David Lynch here, especially his searing 1992 Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me here—overtly, in the overcranked flashbulbs that explode as the cops work over Julia’s apartment and in the carnal furnace of vermilion light that soaks a scene of infidelity, but also subtly, in the deftly drawn web of potential culprits, motives, and societal currents that surround Julia’s death.

Fulci’s camera carries tangible empathy for Carol, even as the truth about Julia’s murder becomes clear. Her subjectivity is the anchor point on which the rest of the film settles—allowing Fulci and Kuveiller the freedom for audacious, even illogical cutting patterns, split diopter and deep-space compositions, and raw-edge handheld movements that communicate paranoia, confusion, terror, and, ultimately, the unreliable perspective of Carol herself.

That warped perspective is underlined by the surrealist and grotesque artists that Fulci references. Carol has a few Francis Bacon paintings in her apartment, which like many elements of her real life recur in her dreams, allowing Fulci the chance to flex some Bacon-esque practical makeup effects. A setpiece toward the end in a massive, deserted church (actually London’s Alexandra Palace) rivals Argento’s tightest work for an overwhelming fusion of sound and image, framing Carol and her pursuer against the Dalíesque blankness of the architecture, massive planes of flat color dominating the image while the church’s electric organ blasts on the soundtrack. Certain shots toward the end, with Carol in a tilted maroon hat which Fulci frames to obscure her or others’ faces, have the no-nonsense surrealism of a René Magritte painting.

The film’s maelstrom of style comes to a head when it is revealed that Carol is responsible not only for Julia’s murder but for constructing the “dream” as grounds for an eventual insanity defense. She not only manipulates everyone around her to prevent Julia revealing their affair but the fabric of the film itself, which presents her dreams and her sessions with Dr. Kerr at face value as genuine expressions of psychic torment. The motive, then, comes from Carol having a lesbian affair with her neighbor that would disgrace her politician father were it to come out. Never mind that Carol’s husband, Frank (Jean Sorel from Short Night of Glass Dolls) is also cheating on her!

The massive irony of this entire scheme is that we see a 1970s London in the throes of the sexual revolution, from Carol’s wild house parties to a commune of hippies that live in an abandoned theater. The repression that drives Carol to murder is coyly set against this rapidly modernizing society, an archaic relic of a passing era. Carol and her family’s luxe bourgeois milieu is literally rammed against the new wave drugs-and-sex in Julia’s apartment next door. There are ways in which Carol is minimized by her gender by her peers, but class makes available to her the apparatuses of medical and political power she plans to manipulate to exonerate herself.

A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin is a genuine masterwork from a filmmaker who’s too often dismissed as gorehound kitsch. It’s literate and risky, with piles of stylistic innovations and juicy subtext that land it firmly among the best giallo—to say nothing of the cinema of the era.