War for the Planet of the Apes is a Joyless Pile of References

A small blonde girl runs with a flashlight down a long tunnel, opposite a wall that reads “This Way Out of Hell” til she reaches a fork, where “Ape-Ocalypse Now” is spray painted in thick white block letters. It’s not actually clear that the little girl can read, but that’s irrelevant. The text isn’t for her, it’s for the audience.

World building graffiti is nothing new, and it being handled like a soccer ball in a U4 summer league game is similarly stale — see Cara Ellison’s take on Alien: Isolation’s graffiti. War for the Planet of the Apes is chock-full of it, graffiti behind Woody Harrelson’s gruff antagonistic Colonel reads “History, History, History” scrawled like the Jokers’ tattoos in Suicide Squad, a sign resting outside the camp pointed to the apes (who presumably also cannot read) says “The Only Good Kong is a Dead Kong.” The side of a guard tower says “Keep Fear to Yourself, Share Courage with Others” like a post-apocalyptic motivational poster. It’s handy that at the end times, taggers are still making time to scrawl out important messages. Bad graffiti isn’t a fresh problem. What makes this particular batch stand out is that it rests inside of a movie that people are so highly praising (the New York Times writes that War for the Planet of the Apes is less a “war film than a western wrapped around a prison movie,” for example). It also stands as a highlight of one of the larger problems in this movie.

There’s nothing subtle about War for the Planet of the Apes.

A movie referencing just Moses and the Exodus of the Jews from Egypt would be more than enough, but War for the Planet of the Apes is not content for the singular, instead piling in nods to other films, the Vietnam War, slavery, concentration camps and Jesus. The story is a muddled creation that does less to create a coherent narrative with the rest of the series (it’s only been 15 years since the Simian Flu outbreak that made apes smarter and killed humans at an alarming rate and somehow jump started an epic apocalypse) and more to pile allegories like firewood. A single one of these would be heavy-handed — all of them together is a leaden weight.

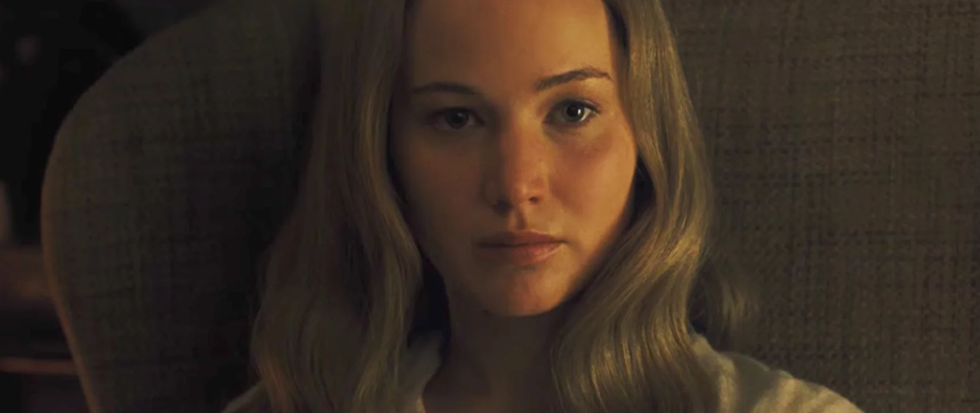

It isn’t just that a movie about a bunch of apes running around the woods talking about freedom takes itself far too seriously, it’s that it does so with the subtlety of a chainsaw. The apes aren’t just slaves to the humans in War for the Planet of the Apes, they’re whipped while the National Anthem plays over a loudspeaker. The US government doesn’t appear to be a thing, but nationalism still reigns. Caesar (Andy Serkis) isn’t just beaten, he’s actually crucified for several days. Apes that change sides to work with the humans have the word “Donkey” spray painted on their backs to show that they have been dehumanized by the human soldiers. Innocent children are waifish and blonde. This movie is a picture book of modern travesty painted in cinematic apes.

This is a movie that takes itself deeply seriously, as though it were a film about World War II when it is actually a third in a trilogy of summer tentpole films. This movie finds Caesar (Andy Serkis in his best CGI mocap performance to date) as the grizzled leader of a mountain community of apes. The apes have been pushed to the war by the deeds of the dead ape Koba, a war that has pitted them against the militarized humans. Caesar seeks a cease fire with the humans to protect his family and his growing “herd,” all he wants is to keep the forest, or to move towards a new home away from the military and the humans. To live in peace. The humans are at odds with this position, and choose to instead kill the apes and enslave them in a weird mountain compound to build an incredibly useless wall.

This part is less important than it seems. The movie is barely about the conflict with Harrelson, who does his best Kurtz but falls more into manic and nonsensical than driven to darkness. He vacillates wildly between calling Caesar emotional to citing a holy war, a line that is delivered blankly and without context. There’s no religion or faith to Harrelson’s Colonel. There’s no substance to him at all beyond anger, but the movie wants you to treat him like a threat.This is the first film in the newer saga to treat humans as directly antagonistic, truthfully they are without merit almost to a man. But they also aren’t given any personality, and as such are easy cannon fodder in one of the films short action sequences. The conflict, if there is one in War for the Planet of the Apes, is within Caesar on how best to lead his people. Will he turn to revenge, like Koba before him, or will he try to maintain peace for the survival of his species and specifically his young son Cornelius?

The entire film is dedicated to the same dark blue black color palette that seems standard for big action releases. The only real movement occurs in the fight sequences, which are frantic and also blue black. If there’s one saving grace to the film it’s that midway through the movie they move to a snowy mountain, so the dark trees are occasionally broken by white plains. The movie isn’t muddy, not really, and the computer generated effects are the best they’ve been in the series (aside from an avalanche near the end that is nearly unrecognizable from a flood). It’s just that there isn’t much that is visually interesting about it. Male and female apes are difficult to tell apart (except when you notice that the designers have given them the equivalent of bows in their hair), and except for a few notable apes (Maurice, Rocket, Winter) most of the apes are the same dark furred chimpanzees. It makes it difficult to connect with most of the supporting cast of apes, which are nameless creatures thrown into an incredibly unforgiving movie.

War for the Planet of the Apes, on top of being gifted with that incredibly unwieldy title, has issues resolving loose ends. Threads pulled early on, waved in front of the audience, are left unsolved at the end of the run time. What was the takeaway from saving the human crossbow sniper Preacher? What about the tunnel nearly caved in with rushing water? What about the other apes that may have escaped from zoos? These concepts are introduced and then quietly pushed aside in favor of Caesar coming to terms with his leadership.

One of the elements introduced is a new illness that turns humans mute and feral. Harrelson’s band of soldiers believes that the illness is a plague, something that must be eradicated by murdering everyone who suffers from it and then burning all of their possessions. The audience is shown, through a series of encounters with a girl driven mute by the illness, that the disorder just robs her of her voice not her sense. It makes it difficult to take Harrelson seriously, and it is another in a series of uneven characterizations meant to paint him mad but instead making him seem poorly conceived. Does he think the apes are intelligent or not? Does he want them to survive or not? It’s unclear, and Harrelson and the general direction of the film seems uninterested in sussing it out.

War for the Planet of the Apes is nearly 2 and a half hours long, and will undoubtedly be released with a longer director’s cut to showcase more of the plodding dialogue and pile of references that the director decided to include. It’s a lean two and a half hours, if such a thing exists, but it’s still self-serious enough to think that a movie about a chimpanzee needs to be that long. Epics have had more restraint. War for the Planet of the Apes lacks joy and fun, and sacrifices them instead for a show of CG ape-manity, torn flesh and bombed out shelters. It’s decent CG, but by the fiftieth grimacing ape face you may just have enough.