“Semi-fine Dining” – Ristorante Paradiso

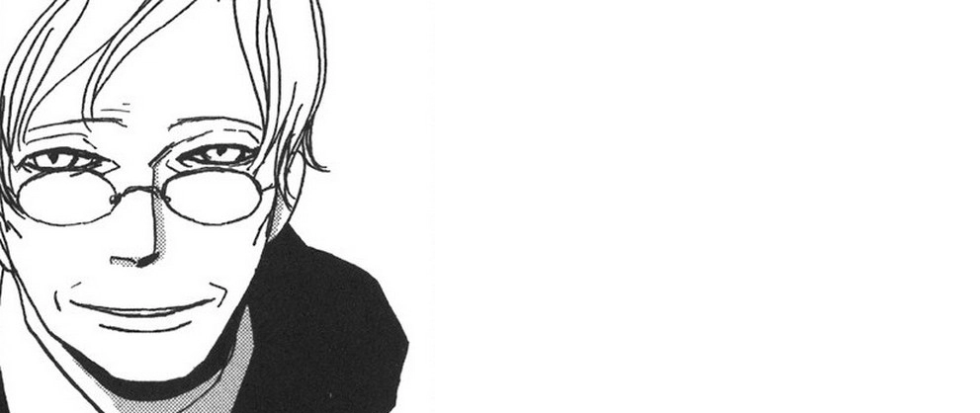

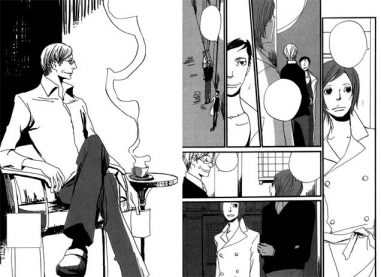

Natsume Ono has a reputation for penning manga that detractors might damn as “hideous” and which proponents might more readily call “elegant” but which have always struck me as “distinct.” There’s little denying that she strives for elegance: whether chronicling the crises of identity suffered by a gang of Edo-era kidnappers in House of Five Leaves, the misadventures of modern police in Coppers or youthful malaise and disaffection in Not Simple, she has an undeniable preference for characters as willowy and severe as models, and for surroundings as angular and sparse but bold as a set designed by a team of modernist decorators and architects. Even her panel arrangements, which favor wide and long or tall and thin shapes separated by large, seemingly useless blank spots, convey a sense of stripped-down If she does not devote the same narrative or thematic attention to fashion and style that contemporaries such as Kyoko Okazaki, Moyocco Anno afford it, she is far from unaware of it.

But much as I’ve loved her work, I could not call with total honesty call it elegant. The exaggerated features she is so keen on shade too easily over into caricature, especially when combined: the thin lips, sunken eyes and strong, long chins all her characters are born with form in concert something toadlike on anyone whose faces stretches in an attitude of consternation or consideration. Fine chiseled features on characters so thin leave them too often looking gaunt, work with the glassy stares to leave the characters looking haunted even in a moment of rapture. There is a ghostly cast to her art that is a little too repulsive to be chic but too seductive to be dismissed as ugly. Hence “distinct.”

So it is with Ristorante Paradiso, a love story set in and around an Italian restaurant in the heart of Rome that follows the day-to-day life of the young Nicoletta as she tries to work her way back into her mother’s life. At first she means to do this by threat: her mother Olga abandoned Nicoletta to her grandparent’s years ago to marry the restauranteur Lorenzo, who specified he had no interest in any woman with kids. Slowly, though, her motivations change as she comes to know the various handsome gentlemen who serve as the waitstaff and chefs at the restaurant. One in particular – the genteel Claudio – has captured her affection, but the massive age gap between them and the former’s own lingering feelings for his ex-wife Gabriella (now herself a divorce lawyer) conspire to keep them apart.

It’s a wistful fantasy, as drunk on the idea of these romantic capers and this idyllic lifestyle as it is on any of the questions of family and love that seem to be the center of the story but are only so abstractly. Surely it’s no coincidence that Nicolletta’s estranged relationship with her mother is paralleled in no small way by the strains afflicting every other family in the story: grumpy server Luciano often finds himself saddled raising his grandson Francesco while his own daughter runs off to enjoy herself in a clear reflection of Nicoletta’s own upbringing. Lorenzo and his older half-brother Gigi would never have become business partners if the latter’s vindictive father, still resentful of Lorenzo’s father for stealing his wife, had had his wish. “There are so many different shapes to love,” Nicoletta thinks to herself upon hearing this story and considering how it reflects her own relationship with Olga and, again, with Claudio.

What these shapes might be, though, Natsume Ono never rightly investigates. She seems convinced it is enough that anyone feel anything at all; as Olga has it, love is little more than being “happy whenever (somebody’s) around.” When you “find (yourself) chasing (them) with (your) eyes.”And though Olga is later castigated by Gabriella for being a terrible mother, she and various other characters affirm that Olga remains an amazing woman, one Nicoletta could learn much from, with the implication that Nicoletta’s decision to abandon the resentment she harbored her mother was the right one all along. Pain means little in the face of pleasure, it would seem: no character in Ristorante Paradiso is treated so poorly by the author as Gigi’s bitter father, who pays for his spite with his life.

Indeed, what could be more dignified than such an Epicurean lifestyle, unanchored by the heavier emotions, devoted to the pursuit of scrumptious food, high fashion, handsome men and easy pleasure before all else? The shape of love as Natsume Ono has it is undefined, textureless, amorphous because always changing but still in possession of some immutable essence easily recognized by those open to it. There’s no denying the appeal of this ideal – it is the strongest element of the romantic myth of beauty as the highest good, and nothing captivates like beauty – but it is sustainable only in a world that allows such an easy life and which privileges such simple emotions. When thrown into relief by starker reality, though – by more nuanced works, by more observant writers, even simply by our own complicated lives – this elegance begins to look strained, contradictory, flawed, much as Ono’s own art does when compared to the art of more elegant creators.

Not that it would be entirely fair to hold the rest of Ono’s work in suspicion of these same shortcomings. Ristorante Paradiso, despite sometimes lofty airs, is still escapist fantasy. It is only in later works, such as House of Five Leaves, that Ono begins to more studiously, more honestly explore the questions of identity and regrets that dog her character, and in doing so grasp onto the elegance she only formerly grasped after. With the best of her comics the contrast between her ethereal art and the ugly reality of these lives generates an uneasy attraction that gives way to tension; here, where the art and story are in concert, there is no such tension, no depth, little body. Just a pastry as scrumptious and flaky but airy as any you might find in the titular ristorante.

Not that it would be entirely fair to hold the rest of Ono’s work in suspicion of these same shortcomings. Ristorante Paradiso, despite sometimes lofty airs, is still escapist fantasy. It is only in later works, such as House of Five Leaves, that Ono begins to more studiously, more honestly explore the questions of identity and regrets that dog her character, and in doing so grasp onto the elegance she only formerly grasped after. With the best of her comics the contrast between her ethereal art and the ugly reality of these lives generates an uneasy attraction that gives way to tension; here, where the art and story are in concert, there is no such tension, no depth, little body. Just a pastry as scrumptious and flaky but airy as any you might find in the titular ristorante.