“Isolation” – The Girl from the Other Side, Vol. 2

The most arresting moment in all The Girl from the Other Side’s second volume is its most understated. Fitting given how much atmospheric and thematic effect the first volume made of silence and subtlety, but surprising because it follows so much that has been so striking. The confrontation between Teacher and the interloping Other he found cornering Shiva at the end of the last volume – all close, sharply canted angles and jagged inking that conveys the chaos and claustrophobia of the physical struggle between these two as well as it does Teacher’s fears and despairs as he finds himself turning into a monster before Shiva’s eyes to protect her – is a masterclass in unsettling violence made all the more disturbing because it is the first time artist Nagabe has broken this world’s stillness to show what was always moving beneath it.

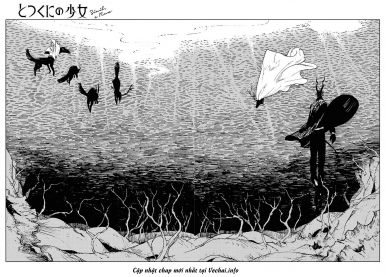

The subsequent journey Teacher and Shiva make to a gargantuan lake alongside the Other and his ilk to meet the entity they call “Mother” is a succession of lyrical splash pages and spreads so beautiful that they immediately outshine the visceral shock of earlier pages. Images of Teacher sinking to the inky bottom of the lake with the head of the Other in his hands, cape trailing behind it like a bridal veil, of Teacher and the Others gathered around the hole whence issues the “songs” of mother: these images and so many others evoke something of the dread and wild wonders that lurk in the oldest fairytales. Nabe’s command of lighting, of water effects and of inking, is such that few pages pass without some visual marvel to catch the eye. One has only to look at how she renders reflections of Teacher in puddles and their subsequent disintegration as a leaf sends ripples through them, how she turns the shadows cast by a flickering midnight candle into the manifestation of Teacher’s internal doubts, to understand something of this world’s peculiar character.

And yet all of these displays seem so small compared to a single-panel of Shiva’s clasped hands from her point-of-view. At first it reads as if she’s watching them to make certain that they display none of the symptoms Teacher has just warned her will attend the curse spread by the Others’ touch, holding them to affirm they are still as they appear. As if once she stopped holding them against one another they would morph in that moment of doubt into the charcoal-black claws of the Others, of Teacher. Children who’ve just been told they might be sick or are scheduled for surgery react similarly, desperate to affirm that these are only words they’re hearing, words divorced from any material reality. And there is certainly something of that apprehension in Shiva’s face in the preceding and subsequent panels.

What is so striking about this image is not a childhood girl’s moment of doubt or first intimations of mortality. No, what strikes here is how perfectly this moment encapsulates every theme that Nabe has been building in these first two volumes and how perfectly she captures these thoughts in a single, understated panel. For while Shiva is no doubt contemplating her own fears of contamination, of corruption, it is clear that she is also considering as well the life that her surrogate father has been condemned to. “First, your sense of touch dulls. You lose the ability to discern texture or temperature…eventually, you lose the ability to feel any but the most basic sensations. Until, finally…you’re left like me,” he describes to her as he considers his hand, and in the way she gazes at her own in imitation we begin to see her coming to understand the pain that her surrogate father must feel in being unable to spare her even the smallest token of physical affection. We see a child awakening to empathy, its blessings as well as all its attendant curses.

While it’s a condition that has been made apparent to us before in dialogue and a number of clever details – such as Teacher’s ability to hold a burning log without problem and his tendency to char everything he cooks – it is in this moment that the emotional reality of his condition becomes unbearably real to Shiva and reader both. How miserable it must be to live in a world you are at the same time shut off entirely from? How much doubt must a soul who literally cannot feel what is around him – who can only make sense of it through sight? – feel from minute to minute? Much as we might deny it, our conception of reality depends on having others around us who can affirm what we see and think and feel; cut off from that everything would inevitably start to feel illusory, the product of a brain left floating in a jar. Such existential isolation leads to a withering of the spirit and madness because it casts everything we witness and everything we feel in doubt: we crave community because without it we would, paradoxically, lose ourselves.

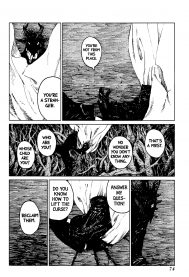

The Girl from the Other Side is a story about people desperate to connect but incapable of doing so. The Others may be able to spread their number, but doing only grows the number of miserable souls in the world; there can be no community between those who cannot feel. Even were their touch not a curse, their deadened nerves insures they would not be able to feel anything they brushed against. The humans hidden on the “Inside,”, meanwhile, turn rabidly on anyone that evinces even the suggestion of the Other in fear that it might cut them off only to, ironically, deny themselves the opportunity for any contact. The wall that surrounds their anodyne, empty city, the armor they wear, the witch hunts they propagate: all of these tools of protection have rendered them too paranoid, too guarded to allow intimacy. The silence that mutes every panel then is just the atmospheric manifestation of these isolating forces, the spirit of a world where that denies people any ability to bridge the gulfs between them. Forms move through this world, but when they seem to connect to nothing else who could be certain that any of them are real? Without those basic signifiers, how much the world must resemble a puppet show projected against a poorly lit wall?

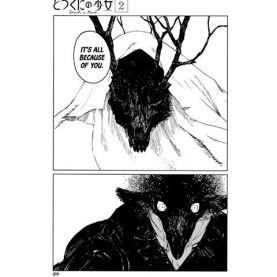

Little wonder then that all of the Others apart from Teacher lurch through the world without eyes: better to remove that last uncertainty than stumble through life forever doubting. Little wonder that they gather around the hole they call “Mother” for a chance to hear her song. As the only thing that breaks up the silence each lives isolated in, “she” offers the only evidence that there is anything beyond their own solipsistic existences. She is the only thing that offers them the chance for community – for connection – that they crave. If Teacher wisely refuses this offer because he recognizes that all it promises is false, he cannot ignore its appeal, just as Shiva cannot ignore the appeal of running off with her aunt at volume’s end. Who could in a world so lonely? We need that connection more than anything; it’s the very reason we turn to works as inspired as The Girl from the Other Side. Few things are as precious as the vision that someone who understands the world can share with us, and Nagabe shares a vision that is one-of-a-kind.