The Past is Never Dead

The Burnt Offering is where Stu Horvath thinks too much in public so he can live a quieter life in private.

The Burnt Offering is where Stu Horvath thinks too much in public so he can live a quieter life in private.

———

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #91. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

I recently took a lengthy vacation at Rusty Lake, a resort known primarily for its mental health benefits and its fishing. My stay played out over a dozen mostly short, mostly free room-escape games, during which I traveled through time, was murdered several times and even caught a few fish. As for the mental health benefits, who can say?

It seems a bit gauche to discuss in an open forum the mysteries of Rusty Lake (the studio developing the games makes also takes their name from the fictional setting, creating a kind of metaphysical wholeness when discussing either one). Suffice it to say that they are multitudes and they unfold themselves, gradually and elegantly, over the course of the series: a dozen strange little moon flowers lapping up the same starlight.

For those who don’t know, a room-escape videogame is not unlike the popular real-world activity. Locked in a room filled with a number of seemingly disparate objects, your job is to puzzle out their significance and connections. Doing so successfully results in your escape from the room. The interface usually resembles that of an old point-and-click adventure and they often embrace that genre’s bizarre sort of logic.

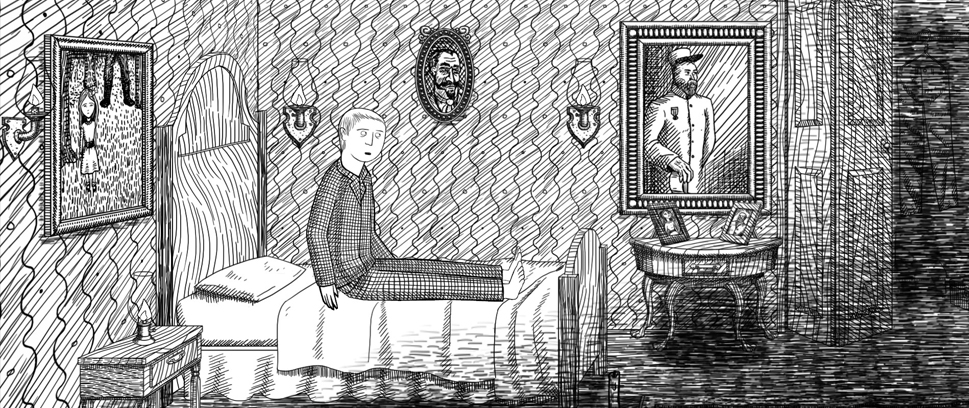

At first, it seems that the Rusty Lake games subscribe to a version of this unfair obtuseness, but over time, it becomes apparent that a surreal internal logic is at play. It may be hallucinatory and hard to predict, but once you acclimate, it has a distinct flow that eases you through the challenges. The games accomplish this through a steady repetition of themes, mechanics and even visuals, to the point that recurrence forms the narrative foundation for all games’ mysteries. Remember that “time is a flat circle” jive from the first season of True Detective? That’s never been truer than on the shores of Rusty Lake.

And so we have the gray parrot named Harvey. When she appears, you likely need to encourage her to lay an egg. A collection of other animals – crow, owl, pigeon, boar, dear, rabbit and pheasant – are also omnipresent, but their meaning is murky. There’s the knife and the box of matches, identical every time you find them, no matter the game. Every house has the same cabinets and the same grandfather clock.

Events repeat. People have spontaneous nosebleeds. Corpse-like arms reach for you. People relive their murders. Unreality also cycles. Impossible things grow, sprouting from unlikely sources, like a tree from a fish. Wounds become caves to crawl into and explore. The woods are always grey. Black figures always climb out of the lake. White squares always draw themselves in the air, portending tragedy.

Often, as with the knife and the matchbook, the exact same art asset is used over and over again. Objects and events, through repetition, become symbols. Traversing a Rusty Lake game is like walking through a dream, complete with its own custom Jungian archetypes.

Or a memory.

You see, the lake, or a supernatural presence within it, feeds on memories. What is memory if not a kind of repetition, a mental replaying of events? A kind of time travel. Perhaps I’ve been here before. Perhaps the game is so mysterious, so muddled, because the lake has already fed on some of my memories.

Maybe that’s why nearly everyone I encounter in the games stares out of the screen, directly at me. It is unnerving, all those blankly staring eyes. Initially, I assigned a kind of plaintiveness to them, a desire to be saved. After twelve games, I no longer think that is true. I now see expectation.

Hunger.

———

Stu Horvath is the editor in chief of Unwinnable. He reads a lot, drinks whiskey and spends his free time calling up demons. Follow him on Twitter @StuHorvath.