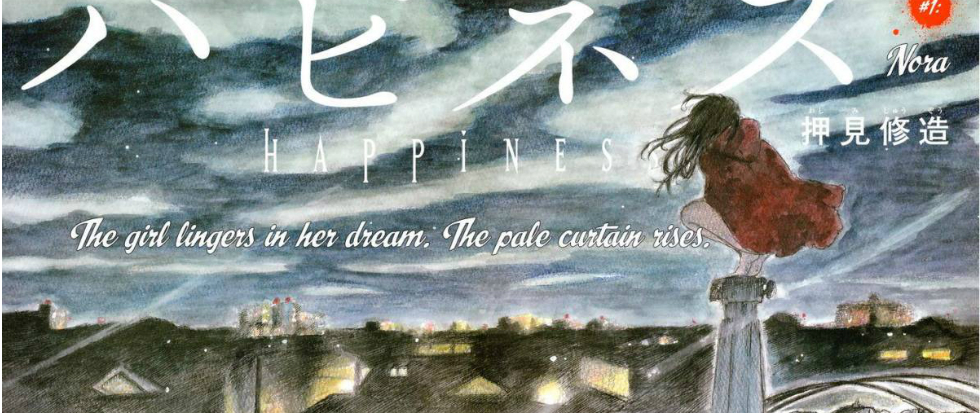

“Eternal Youths” – Happiness Vol. 4

For three volumes, artist and author Shuzo Oshimi has made it clear that the cast of Happiness struggle with growth; with the fourth, he shows how easily these impulses lead us to seek out paths of regression we mistake, in our confusion, for progression. In Gosho’s case this means befriending vampire hunter Sakurane, a man who, like her, has never been able to make peace with the death of a younger sibling. He may seem like a positive role-model for the doubting teen – constructive, motivated, wise – but anyone with perspective can see that his crusade against Nora and her kind is only a clumsy projection of the guilt and self-loathing he’s shouldered for a decade.

In the case of Nora, who until now has been presented as something of an elusive and wise figure, this means latching on to Okazaki as though he were an anchor to who she once was. She has no solution for Okazaki’s plight, no cure and no advice: it should be telling that the only reason Okazaki stalls her murderous impulses at all is that he stirs memories of a past she can only barely remember, more telling that the make-shift coffin she keeps in her dilapidated hideout is composed entirely of moldering stuffed animals. In the end it is she who turns to him for wisdom and a reminder of who she was before her transformation, but the only option he offers her is reversion. “Don’t kill any more people…If you used to be human, Nora…you need to try and get back there again,” Okazaki begs her, as if reversion were a possibility, but if he is willing to join her in her delusions of stasis he also knows well enough to track down his mother for a tearful goodbye.

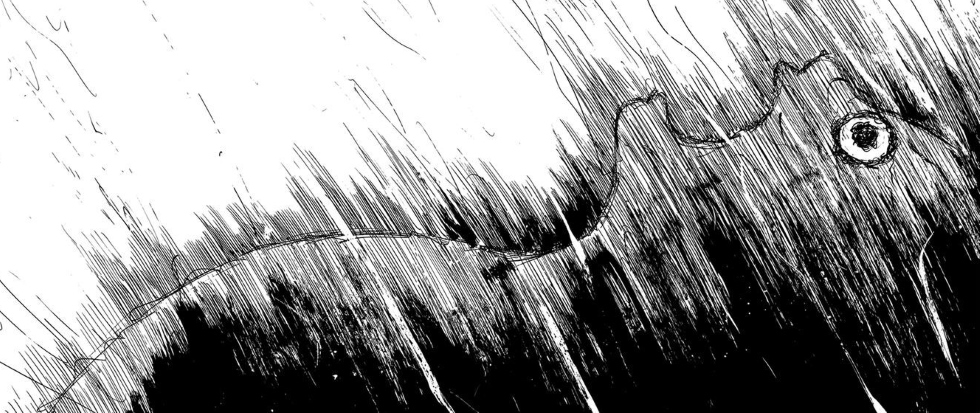

Yuuki, by contrast, may have seemed to embrace his change, but changes in his psyche suggest it is more of a retreat than anything. Granted insatiable appetites and the power to do as he wishes, he chooses not to grow into something new and different but to indulge his basest desires, a decision that in turn reduces him to a childlike state unable to process emotions. When confronted with the authoritative feminine presence of Nora he can only snarl “Mom” at her, as if murdering his own mother has done nothing to resolve his Oedipal complex; when offered comfort and understanding of a nonsexual nature by Nao, the only thing he can think to do is devour her as he did his own mother.

It is only Nao, with this selfless act, who evinces the kind of emotional strength evident of real maturity, yet it is this maturing which spurs Yuuki to kill her, reminding us that Oshimi is not the kind of moralist who rewards and punishes characters in proportion to their growth or degeneration. He knows that justice is not karmic and that our development is not linear. That we aren’t characters in the stories we were told as children, acquiring maturity as a byproduct of age. We’re too complex for that, driven by conflicting wills and subject to relapse, weakness, confusion: the deluded thinking that tricks us into thinking ourselves as always progressing is the same that leads Yuuki into thinking that his decision to accept these changes is a path forward instead of back.

Not he is a satirist, either, conventional wisdom about moral order to expose iniquities in human behavior with a smirk and a sneer. There is the smallest suggestion of social critique as the shadowy organization seen last volume moves to subdue Nora and Okazaki and scrub out any evidence of the existence of vampires (Gosho’s suggestion that these people were responsible for covering up the death of Yuuki’s mom hints at their wide-reaching social powers) but, surprisingly, these overly plotty elements still feel reserved. Even the decision to motivate Gosho’s attraction to Okazaki from last volume now feels more sensible than it first did.

Not he is a satirist, either, conventional wisdom about moral order to expose iniquities in human behavior with a smirk and a sneer. There is the smallest suggestion of social critique as the shadowy organization seen last volume moves to subdue Nora and Okazaki and scrub out any evidence of the existence of vampires (Gosho’s suggestion that these people were responsible for covering up the death of Yuuki’s mom hints at their wide-reaching social powers) but, surprisingly, these overly plotty elements still feel reserved. Even the decision to motivate Gosho’s attraction to Okazaki from last volume now feels more sensible than it first did.

Happiness isn’t flawless. It has significant problems pacing its narrative: four volumes in there have still been only a few minor developments in plot. The grand reunion with Nora that has been built up to since the first volume offered no answers. The sinister organization alluded to since the second volume still remains a mystery. And yet despite all that – even because of all that – Happiness possesses a rare weight of atmosphere and psychology. More importantly, it still possesses the ability to unnerve: the scene where Yuuki slaughters Nao’s family is another high point for the series emotionally and artistically, as beautiful and disturbing as anything that’s come before it. Oshimi is still one of the most daring horror artists in comics at the moment, humane enough and insightful enough to understand the how, why and what of our feelings and daring enough to portray them unvarnished, and Happiness one of the most daring comics being published.