On Preconceived Notions

The Burnt Offering is where Stu Horvath thinks too much in public so he can live a quieter life in private.

The Burnt Offering is where Stu Horvath thinks too much in public so he can live a quieter life in private.

———

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #88. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

When I like something – a game, a story, an album – I seek out more. Sometimes this is easy. Established authors have many books in print, and it isn’t a huge leap to assume that if you like one, you’ll like the others.

This process can be difficult because my enjoyment depends upon something ephemeral. The sound of the spiraling guitar riff in the Sisters of Mercy song “Alice,” the way the scythe in Clive Barker’s Undying feels to swing, how the mysteries at the heart of John Carpenter’s The Thing never allow for a solution. How do you look for more of that? With even only a couple centuries of mass-produced culture, we’ve accumulated a hefty pile of stuff to sift.

The process of creating our tastes would look a bit like a funnel if we were to make a physical model of it. At the wide mouth, you have broad binaries that depend on nebulous personal preferences. I take dark over light, drama over comedy, unhappy endings over happy ones. As we slide down the slope, we encounter the conventions of genres, sub-genres and technical criteria. Give me a supernatural indie siege horror movie focused on isolation and paranoia with a single set and small cast, please. Finally, at the spout, we have if/thens that we reinforce (or undermine) with specific things we already love (or hate). If I love the Sisters of Mercy, then I will probably dig the contemporary band Red Lorry, Yellow Lorry, but might be a little suspicious of Rosetta Stone, a latter day knock-off.

The more criteria you develop, the better the chance you have of discovering things you like. On the other hand, because this system largely draws on things you already enjoy, you run the risk of disappearing into narrow, samey niches.

To account for this, I see a lot of value in poking some holes in the slope of the funnel. That way, I still get to adore a game like The Witcher 3 after loathing the first two installments, or I get to enjoy an ever-expanding definition of heavy metal (Chelsea Wolfe is metal, deal with it).

Recently, though, I’ve noticed problems at the mouth of the funnel, where the decisions are the most basic, personal and difficult to define.

The first happened in December. Over the years, I’ve grown wary of large, corporate intellectual properties and their cross-media tie-ins. There’s always some good to be found (the Thrawn trilogy, Fraction’s Hawkguy run) but it is mostly chaff – (The Courtship of Princess Leia, that Lost videogame). These days, I tend not to take the risk.

In December, I saw a little book called Tobin’s Spirit Guide, named after the reference work frequently mentioned in the Ghostbusters franchise. I picked it up because I always wanted to know more about their system of categorizing ghosts, but I was disappointed on that front. (If you really want to know what a Class 5 Full-Roaming Vapor is, you’ll have to dig up a copy of the Ghostbusters RPG from West End Games.) What I got was a catalog of ghosts and demons from the movies and the Saturday morning cartoon, accompanied by lovely black and white illustrations. I flipped through the book until I saw the pumpkin-headed Halloween spirit, Samhain. That’s all it took to convince me to buy it. Is it a great cultural work? Nah. Does it make me happy? Yup.

In December, I saw a little book called Tobin’s Spirit Guide, named after the reference work frequently mentioned in the Ghostbusters franchise. I picked it up because I always wanted to know more about their system of categorizing ghosts, but I was disappointed on that front. (If you really want to know what a Class 5 Full-Roaming Vapor is, you’ll have to dig up a copy of the Ghostbusters RPG from West End Games.) What I got was a catalog of ghosts and demons from the movies and the Saturday morning cartoon, accompanied by lovely black and white illustrations. I flipped through the book until I saw the pumpkin-headed Halloween spirit, Samhain. That’s all it took to convince me to buy it. Is it a great cultural work? Nah. Does it make me happy? Yup.

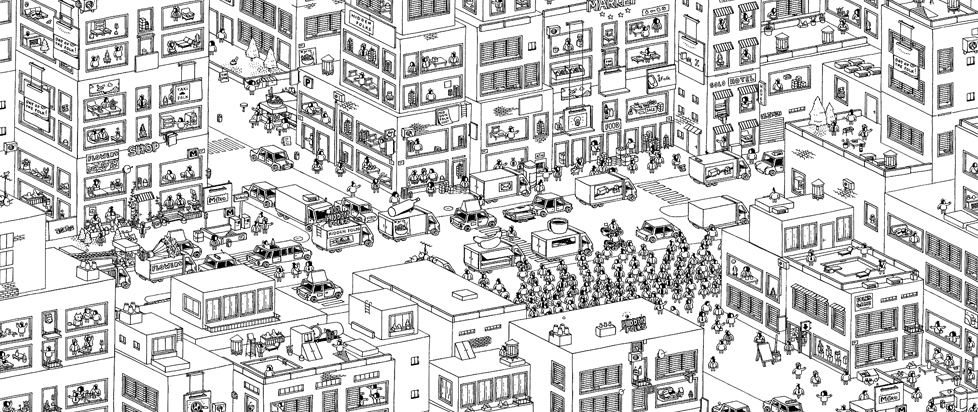

The second happened last week. I got an email asking if I wanted to check out a new indie game called Hidden Folks. I didn’t, really. At first glance, it looked too twee for my taste, but I went to the press page anyway. Man, was I wrong.

OK, I wasn’t wrong about it being twee. Hidden Folks has the whimsy cranked up to 11. What I was wrong about is that I didn’t want to play a sweet little game about finding things in an elaborately hand drawn world. I totally wanted to play that, but I had no idea until it grabbed me by the collar and shook me.

Hidden Folks is essentially a black and white, interactive version of the Where’s Waldo books. You have a list of people and objects you’re looking for. You poke the gorgeously illustrated environment in hopes of finding them. More often than not, you cause funny little reactions and get a sound effect of some sort.

Hidden Folks is essentially a black and white, interactive version of the Where’s Waldo books. You have a list of people and objects you’re looking for. You poke the gorgeously illustrated environment in hopes of finding them. More often than not, you cause funny little reactions and get a sound effect of some sort.

The sounds are worth noting. Try this: using only your mouth, make a sound like a creaky door opening. Got it? OK, now try to sound like a car horn. That is exactly how Hidden Folks sounds. It is endlessly amusing and surprising.

That might sound like there isn’t much to it, and maybe there isn’t, but it is delightful. I played it all weekend. I want more.

The thing Tobin’s Spirit Guide and Hidden Folks have in common isn’t just that they surprised me. It’s that because they are so different form my usual tastes, they stand out in my recollections as bright shining moments in a mass of dark, somber shapes. I’ve read a ton of books in the last two months, but I am still thinking about Tobin’s Spirit Guide. I spent far more time with Tyranny and Darkest Dungeon in recent months, two games that fit my criteria for hits perfectly, but all I want to talk about is Hidden Folks.

How do you create criteria to find more surprises that defy your criteria?

———

Stu Horvath is the editor in chief of Unwinnable. He reads a lot, drinks whiskey and spends his free time calling up demons. Follow him on Twitter @StuHorvath.