The Worst Tool in the Toolbox

It’s easy to hate a rapist. Especially the graphic kind, the one that sees a lone woman and decides to rip her clothes off and push her to the ground. It’s easy to hate that kind of guy — his usage of sexual violence is a clear sign that he’s up to no good.

In the B-Movies of yesteryear, this was often used as a shorthand for the audience. Need to show, and I mean really show, that your antagonist is a bad dude? Make him a rapist. For classic schlock, this wasn’t limited to the primary antagonist but anyone who sided with him. Henchmen that would go for their belts the moment a woman was alone, men who were always prepared to throw open a blouse or hike up an unwilling skirt. You’ve got less than 90 minutes, and about half of that needs to be explosions so there’s little time for true character development.

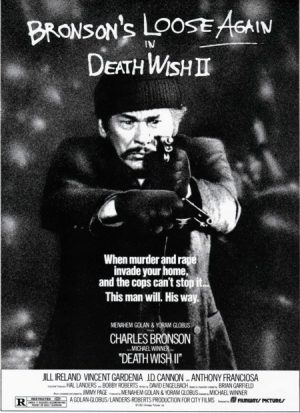

It creates a minefield for watching exploitation films. The franchise Death Wish was built on a pyre of vigilante justice and rape. “All of his family has been raped and killed at this point, we’re the third movie in. They’re all raped to death. His wife. His daughter. His maid. His mother. The dog. Everybody has been raped,” Jay Bauman summarizes the plot in an episode of the Internet web series Best of the Worst. He’s being slightly hyperbolic, but only just. The first Death Wish film begins with the rape of Paul Kersey’s daughter. Her rape is not just the catalyst for the whole movie, but the franchise that followed. It makes Kersey’s motivations that much clearer. The creeps and thugs of New York City have raped his daughter, he must exact revenge. You don’t get that sort of easy clarity if they had just stolen a really nice rug.

It creates a minefield for watching exploitation films. The franchise Death Wish was built on a pyre of vigilante justice and rape. “All of his family has been raped and killed at this point, we’re the third movie in. They’re all raped to death. His wife. His daughter. His maid. His mother. The dog. Everybody has been raped,” Jay Bauman summarizes the plot in an episode of the Internet web series Best of the Worst. He’s being slightly hyperbolic, but only just. The first Death Wish film begins with the rape of Paul Kersey’s daughter. Her rape is not just the catalyst for the whole movie, but the franchise that followed. It makes Kersey’s motivations that much clearer. The creeps and thugs of New York City have raped his daughter, he must exact revenge. You don’t get that sort of easy clarity if they had just stolen a really nice rug.

Hell Comes to Frogtown begins with our character Sam Hell being accused of a rape to establish his virility. When the escaped convict from Alienator finds his way into a new body, the first thing he attempts to do is rape one of the coeds in his group. Blood Debts begins with a rape of the main character’s daughter. Terror in Beverly Hills has the President’s daughter being sexually assaulted to show that the terrorist bad guys do mean business. The Killer Eye features a 6 foot tall eyeball that sexually assaults and impregnates women using its eye stalk.

Like many exploitation elements, it has seeped into popular culture. Take two big budget Westerns from earlier last year: Hateful Eight and The Revenant. As detailed in this article from early last year, the movies both use rape as a tool for communicating about their characters. But they’re certainly not alone. Of the many violations shown to the dead girlfriend in The Crow, perhaps the most graphic was her sexual assault. Zack Snyder frequently has the women in his films raped (300, The Watchmen or Sucker Punch). Or even in the opening of Kill Bill, we learn that the Bride has been repeatedly raped by her nurse Buck while she was in a coma. Tarantino, a noted fan of schlock cinema, is a frequent abuser of the “rape as a tool” motif.

Some movies love to “take back” the rape plotline, try to use it to showcase the revenge of their character. Kill Bill is a prime example of this. The first kill, chronologically, that the Bride makes after regaining consciousness, is her rapist. You see it in Jodie Foster’s 2007 film The Brave One or the Wes Craven classic Last House on the Left. But it’s a shallow sort of victory. “Many viewers/critics see the rape revenge film as only a small step above the slasher film, a sub-genre devoted to the humiliation of women but is nevertheless hidden behind the somewhat transparent banner of feminism,” Kier-La Janisse of Cinema Sewer writes. These are not feminist tales of women rising up against their captors, they are the same shallow uses of sexual assault, just wrapped in a shiny new box labeled “empowerment.”

The callous usage of the rape is still there, even in a rape revenge flick. Because, for film producers, the rape is two fold. In several indictments of Zack Snyder’s work, including this one, he’s been accused of sexualizing a rape scene, specifically by shooting these scenes in means meant to titillate. In the Grindhouse days, this was also the case. You show boobs because you have an easy means to show that the antagonist is a bad guy and also because for a second, you get to flash some boobs on screen. Violence and sexuality intrinsically linked.

Classic schlock can at least hide behind being a product of the times. They’re moving paintings of the cultures that spawned them, the tough guy machismo that needed to be put into effect to save women from the creeps that prowled the street at night. Modern movies don’t have the same armor. They’re the products of little boys who grew up watching these flicks at now shuttered theaters and on late night cable, who are now grown men who use the same cheap tricks to push the audience to their side. To flash a little more skin than they would be able to in a simple assault. They’re cheap tricks in million dollar hands.