Happiness Volume 2, “A Lovely Monstrosity”

Find Austin’s thoughts on Happiness Volume 1 here.

—

The horrors in Happiness accumulate slowly. There are no jump scares, no shocking spectacles, no gratuitous gore: even a disembodied talking head seems deadpan when drawn by author Shuzo Oshimi. All the terrors on display here are psychological, developing at the same languid pace as the characters and plot. It has taken the better part of two volumes for protagonist Okazaki to realize that the late night assault that landed him in the hospital has also turned him into a vampire; there are hints now but only hints that suggest why classmates Gosho and Yuuki are so lonely that they would be drawn to form friendships with our nebbish protagonist. Oshimi’s artistic philosophy seems to be that haste leads to wastes, to squandered opportunities, and so he wastes no time at all getting anywhere.

Everything is in its right place.

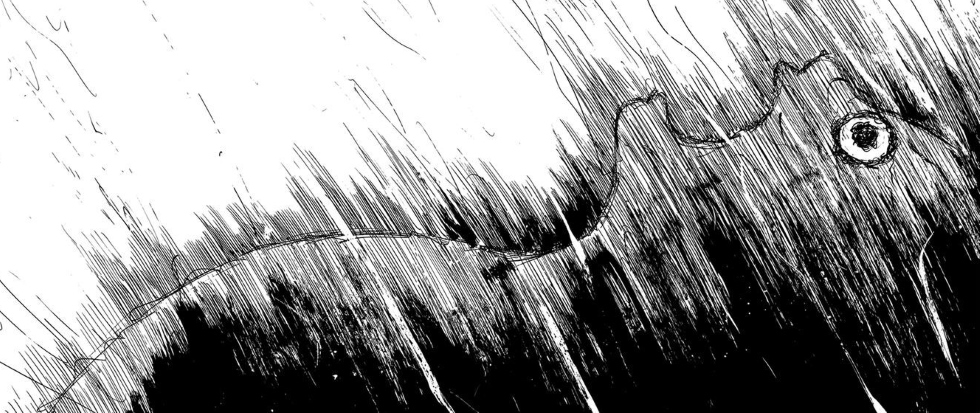

Story beats come only as the characters and emotions at play have been allowed to ripen, not a moment before or after. Each panel lands with noticeable weight: rarely does Oshimi allow more than five a page; rarely does he settle for smaller panels. His interests lie far more with conveying atmosphere, time and aspect than with action, and so he privileges larger spaces to emphasize these elements; he is not shy about using single-panel pages or even double-page spreads when he must. In its lack of haste and its privileging of atmosphere before plot, it often resembles Flowers of Evil, but where that work often felt heedless, as if at the mercy of the same wild sexual energies and anxious yearnings that animated its characters, Happiness feels controlled.

It feels like something happening behind a glass screen in a lab somewhere, trotted out for study by those terrified few who would like to understand it and so rob it of its capacity to frighten. It’s not distant, necessarily; at certain moments it brings the reader in so close that they can feel subsumed. One thinks particularly of those instances where the art style bends to match Okazaki’s own shifting worldview. It was an effective tool for putting readers into his mindset in the first volume, but there it was used so sparingly that it could only hint. Here, thought, it immerses, almost always to disconcerting effect. In one particularly brutal incident Okazaki is mobbed by the same group he fought off at the end of the first volume. The longer they beat on him, the more his bloodlust grows and the more his bloodlust grows the more surreal his perspective becomes, until finally the wavy, impressionistic lines that make up his world give way to one that looks as though it were painted by Edvard Munch, with Okazaki at the middle of it all as the Screamer. It brings us directly into his head at the moment he feels least human, and because it spares no detail and has been built up to page by brutal page, it feels traumatizing.

It feels like something happening behind a glass screen in a lab somewhere, trotted out for study by those terrified few who would like to understand it and so rob it of its capacity to frighten. It’s not distant, necessarily; at certain moments it brings the reader in so close that they can feel subsumed. One thinks particularly of those instances where the art style bends to match Okazaki’s own shifting worldview. It was an effective tool for putting readers into his mindset in the first volume, but there it was used so sparingly that it could only hint. Here, thought, it immerses, almost always to disconcerting effect. In one particularly brutal incident Okazaki is mobbed by the same group he fought off at the end of the first volume. The longer they beat on him, the more his bloodlust grows and the more his bloodlust grows the more surreal his perspective becomes, until finally the wavy, impressionistic lines that make up his world give way to one that looks as though it were painted by Edvard Munch, with Okazaki at the middle of it all as the Screamer. It brings us directly into his head at the moment he feels least human, and because it spares no detail and has been built up to page by brutal page, it feels traumatizing.

Even when the effect is intended to dazzle rather than terrify it can still feel disconcerting, as when Okazaki gazes out unto a night sky that looks like something Van Gogh would have painted. It’s beautiful, certainly, but it’s almost too beautiful. In the way it sparkles and glows with mystic allure, in the way even the electrical lines spark with life, it seems to indemnify the squalid life and people Okazaki has moved beyond. Like the alluring Nora, the vampire who turned him in the first place, it promises a mythical if dangerous alternative to the ugly drudgery he’s always known. What normally should repulse him – what should repulse us – instead lures, which may be why Oshimi practices such control over our point of view and our pace. He knows how quickly our minds become accustomed to terror, how easily we normalize it, but he wants us awake for what else he has to show us. We can’t afford to miss what’s lurking around the next corner.