Keep Your Things in a Place Meant to Hide

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #83, the Love issue. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

This column is a reprint from Unwinnable Monthly #83, the Love issue. If you like what you see, grab the magazine for less than ten dollars, or subscribe and get all future magazines for half price.

———

The internet is great for a fan of stuff. You can connect and bond with other fans, get a sense of participation through sharing fan art and fan videos, and even bask in the illusion of proximity to the artist you love through social media. Although it isn’t unique to music fandom, what you can often do there is download an artist’s entire life’s work – including “rare” B-sides, live shows, demos and outtakes – as a cluster of digital folders nanoseconds after the itch to do so arises. The greater concern there, typically, is fear of sparking a lawsuit, not going against the artist’s wishes.

There’s a similar unarticulated tension in the irony that one of the most pointed critiques against the internet as a tool to better connect us coincidentally also stands as one of its greatest defenses: what it means to be part of any community is entirely subjective. For artists whose lives and work stand as the foundation for such communities, the demands of fandom in the internet age can be deeply alienating. The relationship between artist and fan is complicated, even more so when the 24-hour news cycle of message boards and social media continue to celebrate, churn and dissect even after that artist’s career has ended or changed dramatically.

That sense of belonging fans can get so quickly is rarely available to the artists they are appreciating.

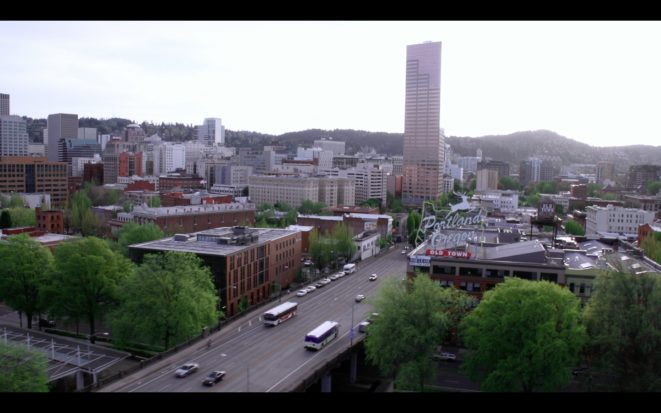

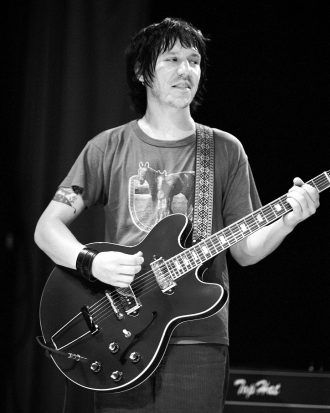

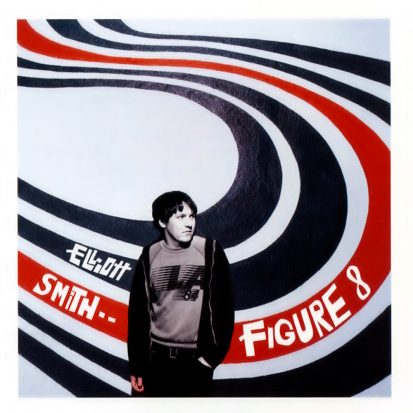

While that isn’t explicitly the focus of either film, a pair of recent documentaries about singer-songwriter Elliott Smith (Heaven Adores You) and West Coast radio personality Marco Collins (The Glamor & The Squalor) are two attempts at making sense of success in the music industry and the whiplash that shortly follows. In Smith’s case, 2015’s Heaven Adores You is intended as a primer to his life and catalog of beautifully bruised songs about love, survival, pain and longing – both cut short by his death in 2003. In Collin’s case, 2016’s The Glamor & The Squalor chronicles how the DJ who “brought grunge to the airwaves,” breaking bands like Nirvana, Pearl Jam and Beck, was forced to re-examine his life and career in the wake of, among many things, the internet.

Kevin Moyer, who went to high school with Elliott Smith, served as producer on Heaven Adores You and music supervisor on both films. They are different stories about different men, but they are both fixed on separating myths from realities and about tracing and crediting each man’s legacy and influence and influences. Those are all big words that are easy to read, write and say, but difficult to fully process: legacy, influence and myth. Never are those concepts more fiercely debated than after an artist dies or they aren’t able to work in as impactful a capacity as before.

Moyer – who is currently working on five upcoming albums and films – talked to Unwinnable about the thorny way the internet commodifies music while also making it universally more accessible, the internal debates and discussions that take place when determining the most respectful way of extending a dead artist’s oeuvre, the death of radio, gatekeepers, buffets and cavemen.

Every year is a year where rockstars die. Sometimes it’s more deeply felt and this year is no exception with Prince and David Bowie. Elliott Smith isn’t the first popular and respected  musician to pass away, but something even the most devoted fan will not know much about is what it’s like being in that inner circle, that nexus point while the world mourns. What is it like having been Elliott’s friend and watching the world mourn a caricature of the person?

musician to pass away, but something even the most devoted fan will not know much about is what it’s like being in that inner circle, that nexus point while the world mourns. What is it like having been Elliott’s friend and watching the world mourn a caricature of the person?

Kevin Moyer: Well, first off, I wouldn’t say I was a friend. Hopefully I’m being a good friend now.

I released some of his music, we went to the same high school, and we certainly had conversations. We ran in the same circle and had the same friends, but I don’t wanna come off like I knew the guy intimately. There’s a hundred people in Portland who knew him far better than me. That said, he had a profound effect on me via the limited interactions we did have. He was kind, smart, intelligent, humble, gracious, really compassionate and he loved music. That’s what most of our conversations centered around.

People are like, “What was it like to know him?” And I don’t. I wouldn’t say I knew him.

Especially with somebody as complex as he was, I think there’s very few people who “knew him.” That said, it’s still a very personal thing. He had this way of making you feel like you were best friends even in the smallest of moments. Even in the shortest of time spent together, he made you feel like you were connected and you might hang out and have a conversation, you might leave that conversation going, “Wow, we’re on the same page and we’re going to be best friends for the rest of our life.” And then you might not see him for the next two years. That was kind of how Elliott was.

It might have been self-preservation. He would open himself up, and maybe he felt a little bit too vulnerable the next day and maybe regret revealing too much, then he would kind of escape and leap back in later.

But to your question about what it’s like to see the world talking about somebody – it’s weird and it’s hard because, especially in today’s age with the internet and Facebook and Twitter, everybody’s a critic and everybody’s an authority. There’s a disconnect there: people forget you’re talking about somebody who was somebody’s friend, somebody’s brother, somebody’s kid, somebody’s bandmate, somebody’s old boyfriend. For the way his life ended it was – it’s the crane the neck at the car crash. People want to know.

There’s that dark kind of fascination of what happened and it’s morbidly interesting to people and they forget that this was somebody who is now severely missed by those people that were close to him. The media was kind of callous right after it happened. It can be cold: “What do you think happened? Did he kill himself or did someone kill him?” And to ask somebody that, who’s just found out about it and just grieving or still grieving is incredibly insensitive.

I feel like the connection with the internet and everything, information is there at people’s fingertips and people can hide behind computer screens and there’s really no connection anymore. It’s a disconnect and you can hide behind these walls and you can feel compartmentalized and it’s easy to forget that you’re asking somebody a very personal question about somebody who is very close to them, just because you’re on the other side of the world on the other end of a computer and you don’t see how they respond. You don’t see the grimace on their face, you don’t see the tears coming down their cheek. They are just an email address. I feel like technology has made the world a bit colder, or at least more distant. We are more connected than ever now, but not person-to-person directly, face-to-face.

I do remember Elliott being asked about the internet in some interview and he seemed to like the potential he saw in it at the time. It sounds weird, but the internet of his day was different from the internet of today even though it wasn’t that long ago. I think what is still true then and now is there can be a feeling in fandom online or off that they know better or more intimately about things someone actually close to a person would know. Did you ever talk to Elliott about the internet and that?

K. M.: That’s the case with Elliott as an artist and his fanbase. They feel like they know him in a close way. The internet aside for a moment, I think a large part of that is because his songwriting and his performance in the way he would communicate his art in music was so intimate. I said this before, but it was like he was tearing open his chest and showing you his heart or you were reading straight out of his diary. You’re reading this and you’re hearing this as a music fan and it’s relatable and it feels like he’s talking about you.

K. M.: That’s the case with Elliott as an artist and his fanbase. They feel like they know him in a close way. The internet aside for a moment, I think a large part of that is because his songwriting and his performance in the way he would communicate his art in music was so intimate. I said this before, but it was like he was tearing open his chest and showing you his heart or you were reading straight out of his diary. You’re reading this and you’re hearing this as a music fan and it’s relatable and it feels like he’s talking about you.

He had this knack for putting enough details in there that it felt personal and relatable, but leaving enough out that it stood the test of time. There was no indicator of, “Oh, this was written in 1988.” There’s no touch points of reference that would make this feel like something that’s out of the listener’s reach. The fact that he would deliver it with a guitar softly being strummed with a mic close to him, with him whispering singing the lyrics, it felt personal. I think besides the fact that he just came across as such a beautiful soul and a kind person his music and art multiplied that by a hundred and made his fans relate and feel like they were even more connected to him.

To your point about technology, now we’re in a world where there’s potential for more to be out there after his death than when he was alive. That’s a weird thing in terms of legacy and artist’s consent. Prince is a perfect example. I love Prince and he had his own issues with the internet and his own thoughts about how he wanted his own art out there. I think that’s legitimate and fair and totally valid. The artist should be able to control how their art is put out there. But as a fan, sadly, after he passed away the floodgates opened and there was all this great content and stuff that you would otherwise would have never been able to see or hear was suddenly out there. As a fan, you could kind of get that. The handcuffs have been taken off and it’s out there. When Prince died, my friend who loves Prince more than anything shared with me his enormous collection of 300-plus show videos and folders and folders of rare and unreleased stuff. There is so much of it. I will have the luxury of going through it and looking at it and finding enjoyment in his art, for many years, even after he is dead and unable to release anything new. So it’s still enjoying the art, and it’s keeping his music alive.

But it’s also that inner dilemma of: okay, he didn’t have this out there for a reason. Who are we as a society and as music fans collectively to decide now that he’s gone he doesn’t have any say, let’s put everything out there? It’s kinda like mom and dad have left the house: Let’s throw a party! Great, but at the end of the day would he have wanted that? You don’t want to trash the house just for your own selfish reasons, because they spent a lot of time building that house and decorating it exactly how they wanted it.

I remember reading a story on Pitchfork where Larry Crane, the Smith family’s archivist, talked about how the internet was mad at him for tracking a song on the posthumous New Moon the way Elliott had intended instead of the way the bootlegs had it for years. So we’re talking here not only about throwing that party, but throwing it in a specific way. I don’t think lines of thinking like that are about getting closure. What do you think that’s really about?

I remember reading a story on Pitchfork where Larry Crane, the Smith family’s archivist, talked about how the internet was mad at him for tracking a song on the posthumous New Moon the way Elliott had intended instead of the way the bootlegs had it for years. So we’re talking here not only about throwing that party, but throwing it in a specific way. I don’t think lines of thinking like that are about getting closure. What do you think that’s really about?

K. M.: Well, I am not sure which song that was regarding specifically, but if anyone knew what Elliott intended in the sessions that he did with him, when he was recording it and in the moment, it would be Larry Crane who I assume was there in the room at the time or at least working very closely with him on those songs. Maybe Elliott performed it different live and that’s what the fans had come to know and love, but that might not have been available to Larry on the tapes. He can only work with what was put down on those tracks, not something that Elliott might have changed later and never included in the recording session that Larry was pulling from. Elliott was always evolving his music, always changing his lyrics and reworking things. So if you are working on something posthumously, at what point of song evolution do you claim to be final, especially if it was never properly finished? You can only do what you think best in terms of what Elliott intended with what he left.

But yeah, that is an interesting example because something was out there on the internet in a different version than the form that it would eventually be released as. You have this enormous collective fanbase, a very passionate one, too, that has taken this other version and grown to know it and love it, and then is very protective of it, in the way that they know it.

If that type of scenario were to begin to happen on a much larger scale, for whatever reason, then you essentially suddenly have an audience building an artist’s legacy, rather than the artist himself.

It’s a big word to throw around: “legacy.”

But when your hands are on the valve deciding what should stay private and what the fans will get to hear, how do you internally figure that out? How do you weigh and decide to honor that person’s wishes about what they would have wanted to keep private and what gets to get out there?

K. M.: There’s two parts to that. Anytime you’re doing a documentary, whether it’s Elliott Smith or Marco, or anything else, you’re talking about somebody – in Elliott’s case, legacy. He’s not around to speak for himself and it’s a huge responsibility because it’s gonna become public record and it’s gonna be shown on this giant screen with a big sound system, and it’s gonna be put on DVD and distributed throughout the world. It’s becoming truth whether it is or not.

That was a big concern, too, when I was working on the soundtrack release for the film. Again, a lot of what we included was stuff that was never released. And you question that. If an artist is dead, does his legacy stop there? Does that mean that nothing should ever be released again? That would be unfortunate because I feel like keeping his music out there and in people’s hearts and minds is a way of keeping him alive in a way, or at least remembered. But at the same time, you are dealing with someone else’s art and making decisions for them, and all you can do is make sure you are doing it for the right reasons and not doing anything that’s going to tarnish anything either. I definitely consulted with those closest to Elliott when I was doing that: we decided that even if there was something incredible music-wise, if we didn’t think he would want it out there for whatever reason, then it was not included. At the end of the day his legacy and the respect for him as an artist is the most important thing.

Do you remember any points of contention or discussion about maybe holding certain things back from the public? Be it songs, anecdotes, or anything?

K. M.: One of the things we wanted to do to alleviate that concern is that we wanted to let Elliott speak for himself. We thought that was creatively cool to do, but also responsible to do because who knows better than him? That’s why we used so much of his music, because we let him speak through his lyrics and his songs. We drudged up every interview we could find and used clips and as you’re watching the movie you hear Elliott himself talking. That was one of the ways we went about that, was letting Elliott speak for himself.

Between me and the contributors, before, I was reaching out to these people who were very hesitant to talk and go on record for many reasons. There was  still a lot of grieving and a lot of pain and the fear of going on public record, the fear of seeming like they’re an authority for somebody that was so complex and shy and not putting themselves out there to the media. So there was hesitation from everybody that we invited and there was a lot of conversations between me and them, just commiserating and saying, “Listen, I know for you this is a sensitivity. We don’t have to go there.”

still a lot of grieving and a lot of pain and the fear of going on public record, the fear of seeming like they’re an authority for somebody that was so complex and shy and not putting themselves out there to the media. So there was hesitation from everybody that we invited and there was a lot of conversations between me and them, just commiserating and saying, “Listen, I know for you this is a sensitivity. We don’t have to go there.”

Every single person we spoke to had something that was unresolved. Some kind of lack of closure. I’m not just talking about a personal relationship that ended too soon because of his death. Depending on who we’re talking about, he broke up their band or he broke up with them as a girlfriend or he moved suddenly from Portland to New York or he moved suddenly from New York to L.A. He wasn’t very good at that kind of thing. I knew a lot of these people already and getting them to trust us and making them feel comfortable was a big aspect of it. That was a huge job before we even put them on camera.

Once we had everybody on camera, internally – between Nickolas [Rossi, Heaven Adores You’s director] and myself and the other two producers – there were a lot of conversations about what the right thing to do was and how to properly portray it. I wouldn’t say there was any instances of maliciousness or anything, but there were a lot of hard conversations because I was probably overzealous in protecting and making sure that we were sensitive. These other guys, Nickolas is in New York and J. T. [Gurzi, producer] and Marc [Smolowitz, producer] are in California. They could go home to their states. I’m here amongst all these people that I invited to participate. This is my home, this is where I grew up, this is where I went to school, this is Portland, these are all my friends. If we made a mess, I was stuck here. Not only was it my self-preservation because this was my immediate environment, but also having known him and having kind of being in that circle it was important to me.

I mean, every aspect of almost everything was loaded with sensitivity in some way.

It’s such a surreal thing because you scrutinize over every aspect of it and then release it and people form their opinions on it.

It’s such a surreal thing because you scrutinize over every aspect of it and then release it and people form their opinions on it.

There’s a popular fan community for Elliott called Sweet Adeline that was around even when he was alive. I don’t know if it was really him, but I remember a user named (h)hhelliott popped up from time to time near the end. I don’t know if he was turning to the message board for comfort, but this was that stretch of time where he was fumbling and struggling through a lot of shows and there were all these rumors around. Nobody really asked if he was doing okay, people were taking the opportunity to ask when he’d play a certain city next or what a song lyric meant. Any type of fame can be really isolating, or more of an affliction.

But I’m curious to hear if you think the film helped humanize him, or whether he ever talked about finding comfort in his fans.

K. M.: He loved his fans. If anybody took the time to sit there and enjoy his music or listen to his music or come to a concert, that meant the world to him. They were huge.

In regards to the online message board, I do remember that and I do think it was him. I never had a conversation with him about the internet specifically but I would guess just based on the way he was, that he would want to talk to fans. He would reach out and he would want to connect with them. But as you get bigger as an artist you have more and more fans and it would become overwhelming. Like, he couldn’t put himself out there on such a big level anymore with so many people wanting a piece of him.

I would think the internet today would have been a blessing for him because he could hide a little bit. For the same reasons I said earlier, that the internet can be kind of cold because you’re hiding behind a computer screen, but it can make people braver as well. I think it would have been something that he might have appreciated because he could get his music out there on a bigger scale and he could control the conversations to a degree. Well, he couldn’t control the reaction and the comments, but he could post a demo for feedback or he could put something online without the approvals of a record label. He could pop up and talk to people when he wanted to and then go away. He wasn’t stuck at a venue after a show, and a bunch of people lined up to talk to him and he would feel bad if he didn’t have a chance to talk to every single one of them. I think that he would have embraced the internet. That’s speculation but just knowing how he was as a person I feel like it might have been a positive there for him.

Elliott has been turned into so many things: an icon, sometimes a punchline. But he was also a goofball, a movie lover and made prank phone calls. What are things you feel like you haven’t seen said about Elliott that would humanize him in some new way?

K. M.: I think he is humanized as he is, already. It’s easy to hear in his music what his hopes and loves and fears were. I think he wore his heart on his sleeve and showed emotion very regularly. Even if some of the takeaways from his music weren’t always necessarily accurate to his true life, they seem like they are and they feel like confessions. So if anything, he almost seems way too human. Much different than the typical “nothing gets me down” rockstar-like facade or someone who only shows bravado without vulnerability.

This isn’t unique to Elliott, but I think with his fans and any fans, there are strong instances of people turning to strangers and their art to tell them something about themselves. Did you notice a subset of this that’s different from what people Elliott knew and their attitudes about it versus general fans?

K. M.: He would write his songs and his songs would feel personal. A lot of times the lyrics would be almost too descriptive and too spot-on and then he would finesse the song, finesse the lyrics and he would make them more general as a self-preservation thing. It goes back to that knack he had for making it relatable by giving you just enough personal touch points that you think it’s about him but taking enough out so it becomes more relatable for the listener. He put a lot of himself into there, but at the same time a lot of those songs aren’t about him at all. It’s him as a storyteller. He’s looking around and he’s telling stories about people he sees and he’s people watching and then making up stories about that person or touching on stories that you know to be true about that type of person.

I think a lot of his lyrics would start of with his own personal feelings and then it would become more and more vague as it become more and more second or third person or he would be projecting those stories onto other people and go, “Okay, I feel this way about a girl. What if this other person in a different scenario felt this way about a girl?” And he would tweak it from becoming ultra-personal to being more vague and a little more relatable and a little more broad. So it would start being about him and then it would end being more of a story. A lot of artists do that.

I know he would sit down and purge himself if he was feeling a certain way. He would sit down and just purge himself of that emotion through his songwriting and then he would get up and he would feel better and he’d look at what he had: “Oh, this is too personal. This calls out So-and-So a little too much this is a little too direct of a reference.” Then he would soften it up and turn it into something more interesting. I think he felt perhaps that ultra-personal stuff wasn’t of interest.

I think the irony, too, is that probably if he were to release those songs in

a more personal form people would have the opposite assumption and wouldn’t think it was about him at all.

K. M.: Yes. Yeah. Since we’re talking about storytelling, you brought up the internet. A lot of times with new technology and storytelling there’s good and bad, there’s pros and cons. It’s the internet and everybody can access it worldwide and there’s satellite radio and satellite TV and you can get anything anywhere but like storytelling began at the earliest stages. As cave painting and tribal songs. It’s interesting to think about if storytelling started with paintings on a cave wall: that’s great, you got two guys hunting a buffalo.

You can’t get too descriptive with that. You know you’re looking at it. You’re like, “Yeah, okay, it’s two guys hunting a buffalo.” You don’t know if these two guys are friends, you don’t know if those two guys are foes, you don’t know if one of those guys is heartbroken, you don’t know if one of those guys is the guy’s dad, you don’t know what their relationship is in regards to anything other than you’re looking at this cave painting of these two guys hunting a buffalo. The other thing is you actually had to be at that cave. You had to go in there to see that cave painting to see that story and you know that’s how communities and their history and their storytelling evolved.

It started there and then it became communicated through oral history and song and then eventually society kind of figured out how to do writing, crushing up berries for ink and writing on wood paper. That was a little broader because they could share those writings and share those histories on a bigger scale. Horses could take it from one community to another community and the message and story would reach further. Then leap ahead hundreds of years later and now we’re at this place where you have the invention of television where you have four channels and you’ve got radio and to hear those stories and to hear the songs that these stories have become, you had to have one of those four TV channels or you had to be in range of the radio tower. You had to be able to get that radio signal.

Fast-forward to today we have that satellite radio and satellite TV and the internet where everything is instantly accessible anywhere in the world. It’s great because everything’s out there and you can get things instantly, but it’s also taken a little bit away. The intimacy goes away a little bit. You no longer have to go to your friend’s cave to see his wall painting. You no longer have to go to the record store to discover new music.

Whereas before you had to be a part of that community and part of that song circle to hear the song or to hear the music. Or you had to be at the venue to hear it happen. Now anybody can get it anywhere instantly. It’s a whole new way, for better or worse, of disseminating media and story and art and music and it’s good and it’s bad there’s just so much more to it.

There’s a huge historical precedent with posthumous releases. Not so much with cavemen, unless you count museums, but with musicians like Mozart, or Puccini or the Beatles. It goes way back, and there’s something sad about the fact that like you said, Elliott Smith has the potential to put out more music after his death than when he was still alive.

What do you think we’re searching for? Why do we want that? It’s like demanding to see a completed painting when we don’t know why the painting was started in the first place.

K. M.: It’s the internet culture and it’s the rabid fanbase. It’s the collector mentality of, “I’ve got these albums and I want more and more and more why can’t I have more? I can go on YouTube and get more, why can’t I get more and more and more? I want everything.”

K. M.: It’s the internet culture and it’s the rabid fanbase. It’s the collector mentality of, “I’ve got these albums and I want more and more and more why can’t I have more? I can go on YouTube and get more, why can’t I get more and more and more? I want everything.”

That’s true, but I don’t know if it’s just the internet. Cavemen were gathering, but they just wanted to survive.

K. M.: Yeah, they just wanted to survive. They were using those paintings to perhaps tell the next generation what they went through. You had the problem of having to communicate history and stories orally or some other method otherwise those stories died and disappeared.

That’s the thing about the internet now, is now everything is out there and it’s forever. You can’t hide it. It’s good and bad, but it has created this culture of, “I want everything!” That’s not the best thing always for the legacy of an artist. Elliott is a unique situation because almost everything he did is amazing. At the same time, everybody that’s still here and working with his labels and everything else is very protective of what they put out there. They want to preserve his legacy and maybe he didn’t want stuff out there. You gotta respect that and the fans they just – God bless them, they want it for the right reasons because they love him and they just want more and more connection and art. His music is so good. I totally understand why they want it all, but at the same time you have to be respectful of what he would have wanted and you have to preserve his legacy. Otherwise you risk watering down something that was otherwise strong.

It wasn’t necessarily my intention to get us talking about the internet, but I think it’s interesting to talk about how it has changed music. There’s a lot with Elliott and also with Marco on how the internet has changed both their careers for better or for worse.

In Marco’s case, he was someone who was a gatekeeper at a time where that really mattered and there were fewer of them. As the internet has allowed us to be our own gatekeepers, do you think we are better gatekeepers today than the gatekeepers we had for us on the radio or wherever?

K. M.: No.

[Laughs.] I’m laughing because I think about this stuff a lot, have asked a lot of people this question, and you’re the first one to say no.

K. M.: Yeah, I don’t.

I would agree with you.

K. M.: I don’t think we’re better gatekeepers because I don’t think there’s gatekeepers anymore. I don’t think there’s a gate. It’s an open field. There’s so much everything out there. There’s no tastemakers anymore – I shouldn’t say that. There’s tastemakers, but you gotta look at it like back in the day when Marco was on the radio and he was breaking new bands.

The media was much more niche. There wasn’t the internet. You couldn’t go online and go on YouTube to find new music for yourself as easily. Basically, the way you found new music was: you went to the record store and dug through crates and if they were nice enough to let you listen to something you could. But for most part you were stuck with, “Oh, this album cover looks great, I’ll give this a try. I’ll pay a bunch of money, take it home and hopefully I’ll like it.” So, basically there’s just digging in crates at a record store or word of mouth from friends, or catching a show or in Marco’s scenario, you had somebody who was a true tastemaker on the radio. He had a louder platform to stand on and yell about good music, something much farther reaching than your buddy letting you borrow his Walkman on the school bus.

The radio was the only place you could hear music. You couldn’t go online because online wasn’t around yet. Sure, there was some TV programming and you might hear a song here and there on a TV commercial and be like, “Oh, I’m an eight-year-old kid. I’ve never heard this Rolling Stones song before! That’s great, I’m going to look for it.”

For the most part you were stuck with what the radio stations were playing and what they were putting out there. That wasn’t the best scenario either because you had these corporate bigwigs putting stuff on the air that wasn’t necessarily the best of the best or they had existing relations with this label. And the people running these radio stations often weren’t your peers, especially if you were a kid. It was someone your parent’s age playing stuff that they knew would bring in ratings. The reason they would bring in ratings is because these were often established songs and artists that the general population already liked. They weren’t taking any risks.

But then, you had true tastemakers like Marco, who would play what he wanted to play, forget what he was told to play. He would play what he wanted to hear and what he liked. He broke Beck’s “Loser,” playing a 7-inch that a fan sent him. Some fan called into the radio show all the time and was like, “Oh, Marco would like this.” And he sent him a 7-inch single, they played it, and that’s how they broke Beck. Do you think that stuffy older radio exec was going to play some unknown weirdo named Beck, folk-rapping about being a loser slacker? Marco did.

The fact that there was niche media with people controlling the door, that was good and bad both because you really had to put your trust in people who were working on these radio stations and that they knew what they were talking about. In Marco’s situation, he knew what he was talking about and he had good taste and a good ear, so he was only letting the good stuff out the door. A lot of other radio stations and other markets didn’t have a Macro so is that a good scenario? I don’t know. As long as you have people like Marco yes. If you didn’t have a Marco and you just had these corporate shills putting on the new whatever they were told, then not so much.

There is no longer just one or two narrow hallways with only one door leading to these artists anymore. And Marco was the doorman. Now, instead, it’s this giant stadium arena that has multiple entry points all around it, 45 different entry points with a way to get in from wherever you might have parked, and this is now the media landscape, this cluttered open access world. This is where kids can get access to the music they’re looking for. They can go online and before they go buy that new album they can check it out online, they can download some file sharing and they can become their own – they can sample, really. It’s like going to Costco and before you buy the giant crate of the new peanut butter you can get a little sample on a cracker and see if you like it. That’s a really great aspect of it.

The other side of that is you don’t have anyone to guide you, we’re missing people that can help provide direction. Everything’s out there, it’s this giant clutter, it’s like being at a giant buffet and there’s way too much food. You don’t know that, oh, that steak is fantastic or that’s a really good salmon. You don’t have somebody there to go check out the salmon on your behalf. You just have this giant smorgasbord of food and you might fill up on this really bad bread pudding over here because there’s not somebody there to direct you to something that might be better.

Yeah, and then you try to skip out on your check.

K. M.: Yeah, you try to skip out. You’re not paying for your music, then they can’t afford to hire a chef to put the delicious food on the table and the food quality has gone downhill.

And then it’s like, “Why aren’t there any new restaurants in my town anymore?” Then later still it’s like, “Why aren’t there any restaurants at all anymore?”

K. M.: Everyone is cooking meals in their bedrooms now instead. Some good, some bad, but no way to know which, unless you go house to house and knock on every door asking to try a sample.

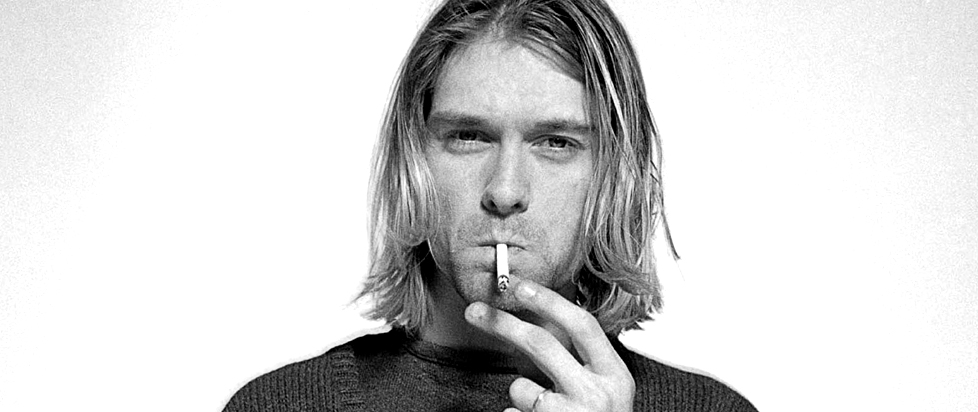

Neither documentary touched on this specifically, but when we lose people like that at bottlenecks that have the potential to catapult talent – can you speak to the way people like Marco might be more thoughtful or empathetic in what their airplay might do to that artist’s life? In the case of someone like Kurt Cobain and even Elliott Smith, I’m not sure you’re left with the impression that fame was 100 percent beneficial for them. Not that anything is 100 percent, but you know what I mean.

K. M.: Well, I think that any artist wants their art to be seen and heard. The fact that Elliott was getting his art out there in a big way had to be very gratifying for him. He wanted people to hear his music he wanted people to enjoy it. I don’t think there’s any debate there, otherwise why release music?

But it’s everything else that came with it. It’s the mythology of him, that he was a big part in helping to build it’s hard to retreat from that. Once you get to a point where your music is out there and people connect to it, they start to feel ownership and they start to feel entitlement and that’s a hard thing to balance. Not only living with these expectations that are now placed on you, but also the misinterpretations. How do you go back to just being this unknown person putting his art out there when everything is on a bigger level suddenly? You haven’t necessarily changed as a person but the people that are interacting with you and your art have. That’s just a really hard thing for anybody and some people are a little more, built to deal with that kind of thing. The rock ‘n’ roll ego.

But then there’s other people like Elliott that just didn’t have that. It just makes it hard.

I remember in the documentary, Elliott talks about how he felt he hadn’t changed much but the only way he could tell things have shifted was because interviewers and the people around him would ask him about different types of things. But there’s no class you can take on how to be a rockstar or deal with it.

I remember in the documentary, Elliott talks about how he felt he hadn’t changed much but the only way he could tell things have shifted was because interviewers and the people around him would ask him about different types of things. But there’s no class you can take on how to be a rockstar or deal with it.

Did Marco ever talk about feeling a little guilty, launching people into that and beyond?

K. M.: I never had a conversation with Marco where he expressed guilt over making somebody’s career. He worked at a radio station and most instances, those people were sending him their music and wanting him to play it.

But when you look at Kurt Cobain, and Marco was really close with Kurt and Courtney [Love] and Kurt’s sister Kim and that would be a real interesting story, to hear him talk about watching that group of people go from small to big. Because, exactly like you were saying, it’s another scenario like Elliott where fame really – I’m sure Kurt loved that people were hearing his music. That’s why anybody writes a song and puts it out there, because they want people to hear their art and hear their music.

Yeah, and I’m sure Kurt got a big kick out of the fact that his career has partially launched in a big way by a gay man.

K. M.: I bet Kurt preferred that, actually.

At the end of that Marco documentary, he says he’s been downloading an album illegally while he was talking. That’s a comment in itself about the state of the music industry and the internet.

This is broad, but how do you feel the internet has changed the way musicians are able to be pioneers?

K. M.: For a musician, it’s great because they don’t need a record contract to get their music out there.

You gotta look at it from two different points. You got these established artists, you’ve got the Rolling Stones and bands like that have a fanbase and were around before the record industry fell apart. They’re already there, they’ve already made it there, everybody already knows who they are. So they’re set. They don’t need to worry about it. The internet for them is a completely different scenario.

Whereas if I’m in a new band and I’m trying to get attention, I don’t have what they have. I don’t have name recognition and how do I get it? Okay, yeah, I can put my music out there but how do I point people to it when there’s everything in the world already on the internet? It’s interesting that the internet is just one media entity that is completely different depending on who you are and what your stature is in the business already. And there’s no difference. The internet is one and the same for everybody, but different as to what strengths and weaknesses artists of different stations can acquire, so what’s a positive for Aerosmith and Rolling Stones is the negative for this new band trying to get attention.

I don’t know the answers and that’s the problem. Nobody knows.

People are always going to make music and always going to make art, but the problem is that we’re gonna lose a lot of good artists because they’re never gonna get heard and they’re gonna have to go get a real job and stop writing songs. They’re still gonna be writing the songs because that’s what musicians do, and there’s those people that just gotta get it out of their system. But the tragic flaw is we’re not going to hear the music. It’s not gonna get out there. We might not ever find the artist who will be the next David Bowie because one guy’s songs about spacemen and spiders get lost amongst all the internet cat videos.

It feels like there’s no more kingmakers but there’s also no more kings.

K. M.: Exactly. Well, I would say there’s no more kingmaking. There’s still kings, but there’s —

No throne?

K. M.: Nobody can find them because there’s so many people out there saying, “I should be king, I should be king.”