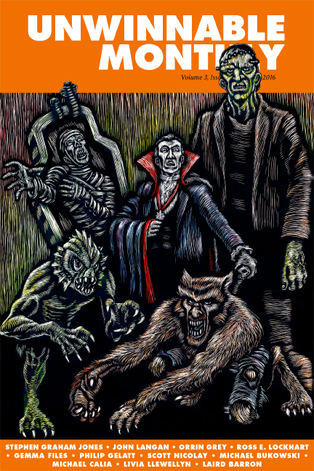

Monster Issue – Theme Recap

Monsters. They’re supposed to scare us, so we don’t wander in the woods, so we go to church and say our prayers. Yet, for all their hideous aspects and dark intents, they remain the objects of fascination. That’s the thing about the Universal monster movies – your classic Draculas and Wolfmen – you’re supposed to root for them, at least for a little while. They have an air of tragedy, of the outsider, of the misunderstood. They are capable of things mere mortals can’t dream of accomplishing and rage, in their own ways, against unjust systems. Of course, they eat people, too, but they’re cool while they do it. Cool get’s you a lot of slack, especially in the pictures.

Monsters. They’re supposed to scare us, so we don’t wander in the woods, so we go to church and say our prayers. Yet, for all their hideous aspects and dark intents, they remain the objects of fascination. That’s the thing about the Universal monster movies – your classic Draculas and Wolfmen – you’re supposed to root for them, at least for a little while. They have an air of tragedy, of the outsider, of the misunderstood. They are capable of things mere mortals can’t dream of accomplishing and rage, in their own ways, against unjust systems. Of course, they eat people, too, but they’re cool while they do it. Cool get’s you a lot of slack, especially in the pictures.

Eventually the monster dies. Some strapping hero gets the girl, the world is saved, blah blah blah. We don’t go to monster movies for the ending – that only serves to return us to the real world. No, we go to monster movies to revel with them.

This month, we asked some of the leading voices in contemporary horror – authors, artists, a filmmaker, a journalist and a publisher, to ruminate on our preoccupation with monsters. Here’s a taste.

“The Monster in the Basesement,” by Stu Horvath (read the full story here)

In the letter from the editor, Stu recounts his evolution from scaredy-cat to horror hound.

When I was a kid, there was a monster in my basement. I never saw it, but I knew it lurked in the corner by the furnace and the water heater.

Once upon a time, when my mother was a little girl, my grandparents finished the basement. They installed a bar, lined the walls with wood paneling, civilized it. The years since had taken a toll, along with the occasional floods that came with the spring rain, but the space remained tamed despite the dampness and wear.

Not that corner, though. The tiles of the floor stopped short there, revealing rough concrete beneath. Pipes dripped. Near the wall was a hole. Sometimes, dark water filled it to the rim. Other times, it was empty, a chute to some impossible black abyss.

Of course there was a monster. And, like the victim in any good horror story, I was ill-equipped to deal with it.

“How Monsters Happen,” by Stephen Graham Jones

Stephen discusses how monsters come into their own in the public consciousness.

It’s easy to dream up a cool looking monster, isn’t it? I don’t know about you, but most of the notes I was supposed to be taking in junior high, they were really long lists of killer features my next monster was going to have. Teeth like this, and spikes on the elbows this time, and big long webbed toes, so you can’t even escape it in the water. Maybe night vision too, and what if it could mimic your mother’s voice, right?

These monsters I designed in words – even in the privacy of my Trapper Keeper, I couldn’t draw – they were encumbered with so many wings and arms and fangs and scales that, had they ever been actually birthed into a real story, they would have collapsed under their own weight, been instantly killable just by dint of how killer they were.

This is all of us, more or less, right? I bet we all have the instinct that the story isn’t judged by how bad the hero is, but by how bad the monster is. A good story comes from the monster being basically unkillable.

Just, it’s that ‘basically’ part I always forgot, once I got carried away with how many teeth I could fit into this one mouth, or into this row of mouths.

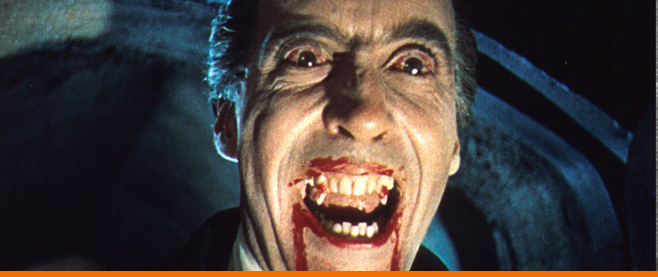

“Vampire Catechism,” by John Langan

John ponders the power the vampire exerts on our imagination.

Not my first Halloween costume, but the first one that was a success. Count Dracula. My First Holy Communion suit, navy blue. White dress shirt, clip-on tie. One of my Mom’s long black skirts, pressed flat and safety-pinned to the shoulders of my jacket to make a cape. White face paint. Plastic fangs that push out my lips. Fake blood dribbled from the corner of mouth down my chin.

Out in the dark in my suit. That feeling of being dressed-up — not adult, not exactly, but formal. Mannered. Never occurs to me that this is the suit in which I first tasted the body and blood of Christ. There’s just the night, vast, cold.

“A Life in the Monster Squad,” by Orrin Grey (read the full story here)

Orrin rhapsodizes the classic kid adventure Monster Squad and the mark it left on him.

That year I sat in the dark on a bale of hay in a long, low 4H barn and watched a projector throw the lighted image of the 1987 Shane Black/Fred Dekker film The Monster Squad up onto the wall. I’ve seen the movie many times in the years since, so it’s hard to say what that first experience was really like. Was I scared? I’d already seen plenty of much scarier movies by that tender age, so probably not. I know that I was in love, and I keenly remember that walk home from the fairgrounds, down the long, barely-lighted streets on the edge of town, the night suddenly electric around me.

When it comes to truly formative influences, it’s always difficult to imagine how differently life would have turned out without them. They come upon us while our molten surface is still cooling, and they change forever the shape that we will ultimately assume. Did I already love monsters and scary stories before I ever saw The Monster Squad? Absolutely. Would I have grown into the person and the writer that I am without that Halloween night in the 4H barn? That’s much tougher to say . . .

“The Face of Frankenstein,” by Ross E. Lockhart

Ross introduces us to the nearly-lost original film version of Frankenstein.

The first cinematic adaptation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus was made by Edison Studios in 1910. It was directed by J. Searle Dawley and starred Augustus Phillips as the young medical student who would create a monster, and Charles Ogle as the monster. In 1910, cinema was still in its childhood, with technology having evolved quickly from the 1890s Kinetoscope, a single-person motion picture viewer, to projectors capable of screening films for a mass audience. Many of the more than three hundred Edison films are simple camera tests, tech demos, showing off what could be done with this new media. But as time passed, the films became more sophisticated, moving away from “actualities” to scripted comedies, dramas and spectacles.

Frankenstein (1910) was indeed a spectacle. Filmed over the course of three days at Edison Studios in the Bronx, New York, the film offered audiences a dashing hero, his beautiful fiancée and a hideous monster, in a story framed by special effects considerably advanced from those of Georges Méliès 1902 A Trip to the Moon. Shortly after it premiered, however, Frankenstein was lost, as studios and exhibitors of the era viewed films as disposable entertainment and, since films were printed on unstable and highly flammable nitrate stock, long-term preservation was nearly impossible. It has been speculated that 90% of films made prior to 1930 are now lost. For nearly a century, all copies of Frankenstein were thought to have been destroyed.

“Gods as Monsters,” by Gemma Files

Gemma peers into the pitfalls of turning somebody’s god into the monster for your horror story.

After all, gods have always ruled both by love as well as by fear, which is an especially important point to consider when looking at any religion from the outside: if we accept that no one thinks of themselves as a villain, then what are adherents to your cult of choice actually looking to get out of this transaction, and why? The difference between a pact with the Devil and a deal with God is all context. . .

Up until the emperor Constantine’s battlefield conversion to Christianity — that obscure Jewish prophet’s post-martyrdom cult which eventually came to be known as “the slaves’ religion” — spread outwards, therefore, re-orienting the entire Byzantine empire, most Romans thought of Christians the same way they’d previously thought of the Jews, i.e. in much the same way that Constable Howie thinks of the pagan cultists of Summerisle in The Wicker Man — as rebels at best and terrorists at worst, dangerously deluded fanatics all too willing to kill for their faith, even though the beliefs that drive them are patently ridiculous.

To Howie, the Summerislers must surely worship the Devil himself, however pleasantly disguised in natural beauty, easy sex and casual nudity, but to them, his pleasure-denying version of Christ must equally surely be either a true monster or a nonexistent fraud. This conflict rather neatly mimics and reverses the course of British religious history, mirroring the way that the triple goddess of the Celtic tribes may have been folded into the concept of the Virgin Mary during Britain’s conversion to Christianity, while pre-Christian gods like Herne the Hunter were simply turned into localized trickster monster-figures like the Green Man.

“A Monster is a Question,” by Philip Gelatt

Phil argues that an unseen monster is the best monster.

A thought exercise. Imagine you’re in a house. It’s large. Gothic. So dark it feels alive with shadow tenants.

You know there’s something in the house. You know it because you’ve heard it. You know it because you have sensory evidence of it. A cracked floorboard. A strange secretion. A scent like rust and rotten summer. An overheard legend, whispered between your parents when you were a child.

Now here you are. In a hallway in this house. At the end of the hallway is an empty door frame. Behind it is a room, unknown. And a sound.

It is that moment, standing there, before the creature appears, that it is at its most powerful.

That open door frame is, in fact, full. It is overcrowded with terrible possibilities. Any moment, something might step into it. Any moment, the monster might appear.

But it doesn’t. And you wait, in dread.

“Stories from the Borderland #16: Van Vogt’s Beasts,” by Scott Nicolay and Michael Bukowski

Scott and Michael share a special installment of their Stories from the Borderland series that charts A. E. van Vogt’s wide and weird web of influence on genre fiction monsters.

Coeurl, in “The Black Destroyer,” is the last living thing on a planet decimated by nuclear war, a predator without prey. “Only too well Coeurl knew in this ultimate hour that he had missed none. There were no id-creatures left to eat. In all the hundreds of thousands of square miles that he had made his own by right of ruthless conquest . . . there was no id to feed the otherwise immortal engine of his body.” Coeurl’s situation is positively sunny compared to Xtl’s in “Discord is Scarlet”: “Xtl sprawled motionless on the bosom of endless night. Time dragged drearily toward infinity, and space was dark. Unutterably dark! The horrible pitch-blackness of intergalactic immensity! Across the miles and the years, vague patches of light gleamed coldly at him, whole galaxies of blazing stars shrunk by incredible distance to shining swirls of mist.” These scenarios are the true stuff of cosmic horror, of The Weird; Coeurl and Xtl are Lovecraft’s Outsider on planetary, even galactic scales: starving, immortal, alone . . . inhuman. Until a ship comes along . . . and we know this story, don’t we?

“When the Wolfbane Blooms,” by Michael Calia

Michael remembers his transformation into a teenage monster.

My grandfather introduced me to James Bond and Indiana Jones. Gunga Din, the 1939 classic starring Cary Grant, Douglas Fairbanks Jr. and Victor McLaglen, was his favorite movie. Once I caught him shedding a couple tears at the bittersweet end of the otherwise rousing action-adventure. . .

As Grandpa John wasted away, I became a preteen. I knew everything and wanted to prove it. I was tired of the blah-blah-blah from the homilies I would hear during the Saturday night Masses I would attend with my grandparents and I was sick of CCD and the pious grind toward making my confirmation. I wanted to transgress and I wanted everyone to see, my grandfather most of all. I didn’t actually think he would die.

I turned away from Universal’s Dracula and obsessed over Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 bloody and operatic Bram Stoker’s Dracula. It was sensory overload; early-era cinematic trickery like shadow puppets and iris wipes melded with the strobing music video sensibilities of the early 1990s. There were naked breasts, too, quite a few of them, and they were the main attraction.

“They Could be Monsters, For All You Know,” by Livia Llewellyn (read the full story here)

Livia returns to her childhood home in Tacoma to find monsters lurking everywhere.

One of the teenage girls claims she saw a wolf rise up on its hind legs and walk across her lawn—other girls have seen this, too, they’ve all seen the beast peering into their bedroom windows at night. Her parents search her bedroom for drugs.

Secretly, the mothers gather over morning coffee and tell their own explicit tales of the creature.

The foreclosed house at the end of the street, have you seen the lights flicker on and off at night?

They say the family in the ranch house, the one hidden behind massive hedges, are all related. You can see it in their eyes.

Five dogs disappeared on the next street over. All the collars were found hanging on doorknobs.

The trees toss and crack as if they’re being split in two, but it’s not windy today.There’s a face in the corner sewer drain.

It’s so boring here, and nothing ever happens.

“Another Me,” by Laird Barron

Someone claiming to be Laird Barron filed a story about doppelgangers.

I celebrated my twenty-first during the annual Iditarod sled dog race with a shot of blackberry brandy from the flask of a great Alaskan adventurer who has since died and more’s the pity. Several days and a few hundred miles down the trail, a blizzard howled from the north and pinned me and my team of huskies on the shore of Norton Sound among the Topkok hills. Those are big, treeless hills blasted down to tough scrub brush, rock, and a jagged rind of ice.

We were trapped for thirty-six hours. Occasionally, as I hunkered inside the sledbag, I dreamed that the storm lifted and we’d made it across the finish line on Front Street in Nome. Wind slapped me awake. It sucked the heat from lungs and wicked those dreams out of my head. The cold wrapped around me, crawled inside me, froze the socket of my right eye, froze my asshole tight as an uncovered spigot on the side of a house, froze my face so the skin later sloughed like a rubber mask, froze my foot until it click-clacked on the hospital tile like Fred Astaire in tap shoes.

Years and years later, I dream I’m back there, that none of us made it through the blizzard. When I snap awake to the warmth of my bed, I stare at the black window and listen for the roar, because for a few moments it’s easier to believe I’m dead.

Artist Spotlight: Trevor Henderson (buy his stuff)

What do you hope to instill in people who see your art?

T. H.: Just the sense of fun you can come across in some horror films. Like when you watch a horror film and it isn’t necessarily scary, but you marvel at the work put into the giant monster puppet made out of latex and animatronics. I like seeing the detail come across on screen. I guess I’d like people to just think it’s cool.

———

Purchase Issue 84 in the back issues section of our store. If you like what you read, subscribe to never miss another issue!