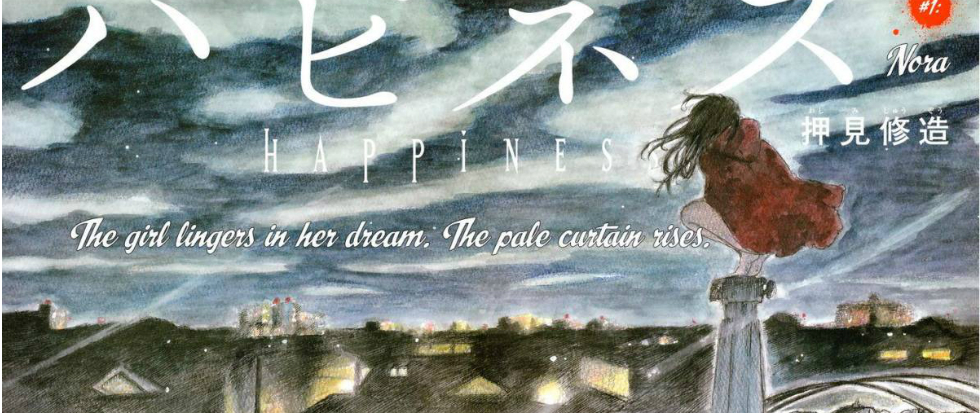

Happiness Volume 1, “A Monstrous Adolescence”

Shuzo Oshimi’s Flowers of Evil was that rare story concerned with adolescence that never slipped into sentimentality or wish-fulfillment meant to assuage teenagers that they were special. It was a uniformly uncomfortable manga series from start until finish, a squirm inducing investigation of the ugly ways romanticism, romance, sexuality and identity get knotted up in our most delicate years and how they might empty us out as quickly as build us up. While it provided redemption in the end, it was not a prize easily gained, for the character or for the reader.

In many ways, Oshimi’s follow-up, Happiness, seems primed to continue that tradition. Makoto Okazaki is a highschool loser who finds himself undergoing a disturbing transformation after a late-night assault by a vampire. Suddenly he has an aversion to sunlight, a bloodlust he can barely tamp down, superhuman strength and a violent streak to match. And it terrifies him beyond compare. “This isn’t me… it’s not me!” he protests after punching out a bully, his horror at his transformation underscored by a spread of sun-dappled photographs from his childhood, reminders of an innocent age, before his body betrayed him.

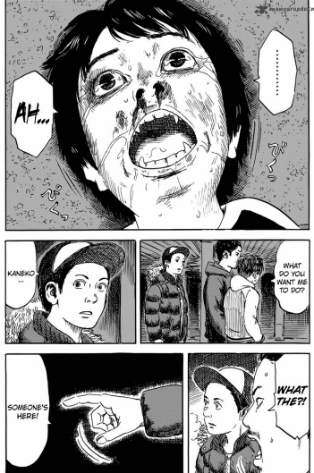

As a metaphor for the horrors of adolescence and the terror one feels as their body slowly shifts into something loaded with desires one doesn’t quite understand, something new and terrifying and other, it runs the risk of being a loaded metaphor. Yet Oshimi makes it work. His art may be gentler than it was for most of the Flowers of Evil, the character’s proportions less awkward, their features less grotesque, but it still manages to capture the essential ugliness of these teens and their feelings, thanks in no small part to Oshimi’s newfound tendency to indulge the expressionistic leanings he only occasionally doled out through Flowers of Evil.

Okazaki’s world is literally oozing, oozing with sexual tension, visible to the reader as lazy, thick waves flowing off of the thighs of every girl who  catches his eye. The sun glares down like a glassy, judging eye. In one bravura section, the panicked Okazaki finds his vampiric mutation has altered his vision, turning a once solid world into something fluid, runny like reflections on water, disrupted by ripples and waves. A number of recurring visual flourishes even recall the arabesque spirals and baroque linework of Junji Ito; Oshimi seems intent on embracing the more literally horrific nature of his story and has done his homework to prove it.

catches his eye. The sun glares down like a glassy, judging eye. In one bravura section, the panicked Okazaki finds his vampiric mutation has altered his vision, turning a once solid world into something fluid, runny like reflections on water, disrupted by ripples and waves. A number of recurring visual flourishes even recall the arabesque spirals and baroque linework of Junji Ito; Oshimi seems intent on embracing the more literally horrific nature of his story and has done his homework to prove it.

Whether or not that will result in a better story still remains to be seen. While the first volume of Happiness is beautifully drawn and populated with a cast promising richness, Oshimi has betrayed small tendencies that might lead to larger problems if not checked. Occasionally the metaphor is too blunt, as when Okazaki’s classmate Gosho mocks his attack on her as the result of “getting so horny (he) couldn’t hold back.”

There is a danger in making literal what is already a bald enough metaphor, a tendency to emphasize the more immediately powerful elements of the fantastic at the expense of the subtle that has ruined other series dedicated to using similar devices to explore similar themes of alienation and metamorphosis such as Tokyo Ghoul and Ajin. While Oshimi is generally a more deliberate writer than that, he would due well to tread carefully. There’s too much promising about Happiness to spoil it on cheap indulgence.