Games Should Make Us Smarter, Not Stronger

Progression systems are everywhere you go. Whether it’s unlocking guns in Call of Duty, earning airstrikes in GTA Online, or simple stat increases in Dragon Age, few games are willing to rely on their mechanical appeal alone to keep players playing. But while +1 perks can be dastardly effective carrots on sticks, their logic can also be quite jarring.

Why does Batman have to earn the right to call in his own equipment? Why does Geralt, a veteran monster hunter and master swordsman, have to level up before he can parry in The Witcher 2? And why is the best equipment in games like Zelda, Darksiders, and Dark Souls just lying around in unlocked chests? Who even puts it there in the first place?

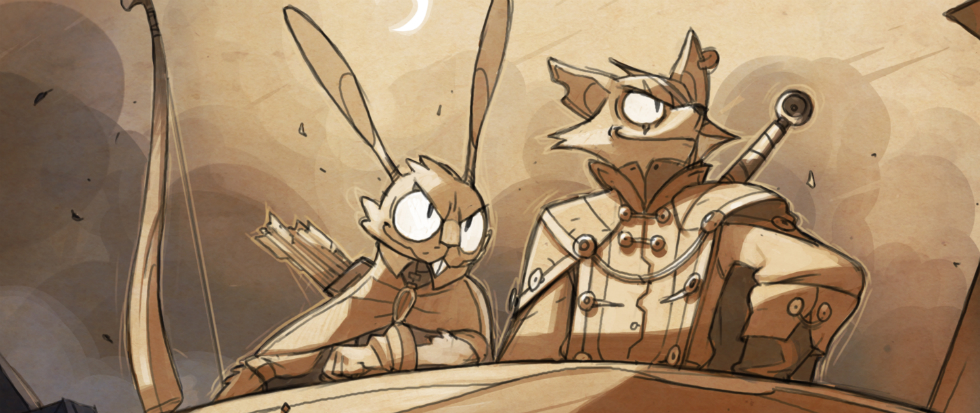

Rather than dismissing these inconsistencies as inherent to the medium, a recent game has taken a different approach to progression. Stories: The Path of Destinies revolves around a looping narrative, where the roguish fox Reynardo navigates a choose-your-own-adventure story to a number of deadly outcomes. Deadly for him, that is. Each end sees him whisked back to the start to try again, only this time he’s armed with valuable knowledge of what not to do.

What sets Stories apart is how it integrates this knowledge into both the narrative and gameplay. Unlike a typical Game Over or Bad Ending, Reynardo remembers the paths he’s walked before and questions the wisdom of following them again.

This simple reluctance avoids one of the major obstacles in replaying games like Heavy Rain or Until Dawn: forcing the player to watch as the characters walk into the same traps and make the same stupid decisions as before. It also strengthens the sense that the player is Reynardo rather than just a passive observer, making it easier to empathize with him and buy into his story.

Stories’ emphasis on building knowledge is not only far more relatable than superpowers and skill trees, it also promotes a healthier perspective on the nature of self-worth. Knowledge represents an inner strength, something that we can all possess if we try hard enough.

Contrast that with unlocking x-ray vision for killing ten enemies in a single combo, or crafting tougher armor out of the pelts of slain prey. These systems preach progression through aggression, and oftentimes don’t even make sense. How does killing bandits in Fallout 4 make you a better lock-picker?

A lot of games tie upgrades to a currency of skill points, or else dole them out when the plot demands it. This often feels jarring and artificial. Yanking the player out of the world to decide whether Delsin from inFamous: Second Son should be a good guy to unlock the heal ability, or turn evil to obtain vampiric powers – never both, because reasons. It’s a harsh reminder of how arbitrary games still are.

Stories’ progress-through-knowledge approach flows far more organically. Reynardo learns by trying and failing, making progress by making mistakes. In this way, he earns his progress, rather than stumbling across it in a locked chest in the depths of an ancient temple. And, without spoiling the ending, the way in which all Reynardo’s discoveries come together is eminently satisfying, and perhaps one of the smartest conclusions to a game that actually takes advantage of the medium’s defining features.

Stories shows that progression in games doesn’t have to mean bigger muscles and badder guns. The narrative itself can serve as character development, with knowledge instead of skill points the currency of progress. Other story-heavy games, especially those that follow the Telltale model, would do well to learn from Stories, even if only by letting their heroes make and recognize their own mistakes. We’re all fallible; why should games pretend otherwise?