Blockhood and the City Organism

While Tim Cook and EA were busy trying to shoehorn in green and eco concepts into their game, Jose Sanchez and Gentaro Makinoda of the Plethora Project were developing such a game from the ground up. Unlike other city builders, Plethora Project’s Block’hood (currently in Early Access) challenges the player to “embark in a story of ecology” and discover the very complex systems of inputs and outputs that governs urban planning.

Inputs and outputs aren’t new to city building but Block’hood’s approach is. In a traditional city builder players are tasked with developing an untouched landscape into a complex machine of glass and steel all the while making money. That money is then used to keep crime, fires, and pollution from tearing the city apart by building police, fire, and sanitation services. Just as a real city planner would.

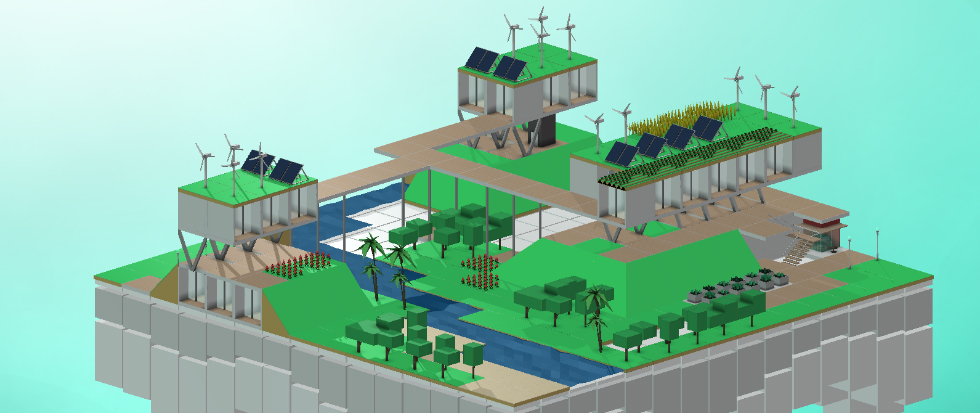

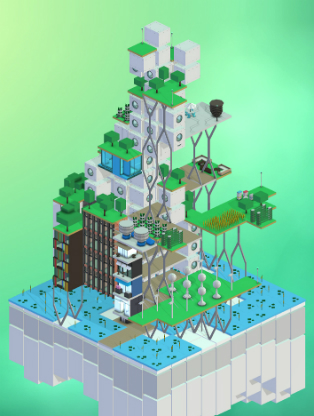

Block’hood asks players to think about “unreal” cities by focusing on ecology. Instead of negotiating taxes and civic services, players must carefully manage decay and a lack of balance within their abstract, complicated block neighborhood. Prosperity is the governing principal and it is only achievable by understanding the intricate systems a neighborhood has at play.

For example, trees produce fresh air and leisure but need water. Water towers produce water but need money. Apartments produce human consumers (and waste) but need water, power and fresh air. Retail stores produce funds but require consumers. Everything in Block’hood is interdependent on everything else, and the resources form a perfect circle of consumption.

This literal interpretation of “ecology” distills what cities really are, organisms. They are one being comprised of many parts, all working to maintain thrive and survive. Block’hood is unique in that the “natural” elements of this organism are not window dressing. They do not solely exist for the purposes  of humans. The humans of Block’hood need leisure and fresh air and must work to provide money to finance the water tower which nourishes the trees which provide that leisure and fresh air. If any part fails, then the ecosystem fails with it.

of humans. The humans of Block’hood need leisure and fresh air and must work to provide money to finance the water tower which nourishes the trees which provide that leisure and fresh air. If any part fails, then the ecosystem fails with it.

Planning in Block’hood has more in common with architectural philosophies like Frank Lloyd Wright’s “organic architecture” than it does with the Magnasanti of SimCity. Instead of oppressive, Judge Dredd-like monoliths, Block’hood encourages players to create Wright-like structures interdependent on their surroundings. To Wright and to Block’hood nature is not a liability, it’s a possibility.

By reducing the scale to just one small area of one neighborhood the delicate balancing act at the heart of every ecological system is laid bare. Too much or too little of any one input or output leads to destruction. Excess leads to decay. Harmony is essential. These are the pillars upon which Block’hood is built and they teach us that the pillars of good city planning are the same pillars of living well.