Is That Dragon, Cancer Really a Videogame?

That Dragon, Cancer has been garnering tons of critical acclaim for its unique portrayal of young parents dealing with their son’s terminal illness. For example, The Guardian calls it “an unforgettable experience” that is “cut through with human resilience and humour.” James Davenport at PC Gamer wrote “That Dragon, Cancer is unlike any game I’ve experienced. I want everyone to play it.” And Nick Wanserski, writing for The A. V. Club calls it “haunting” and “heartbreaking.”

But should it really even be considered a videogame?

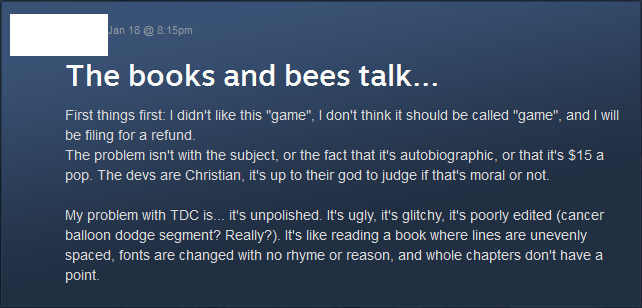

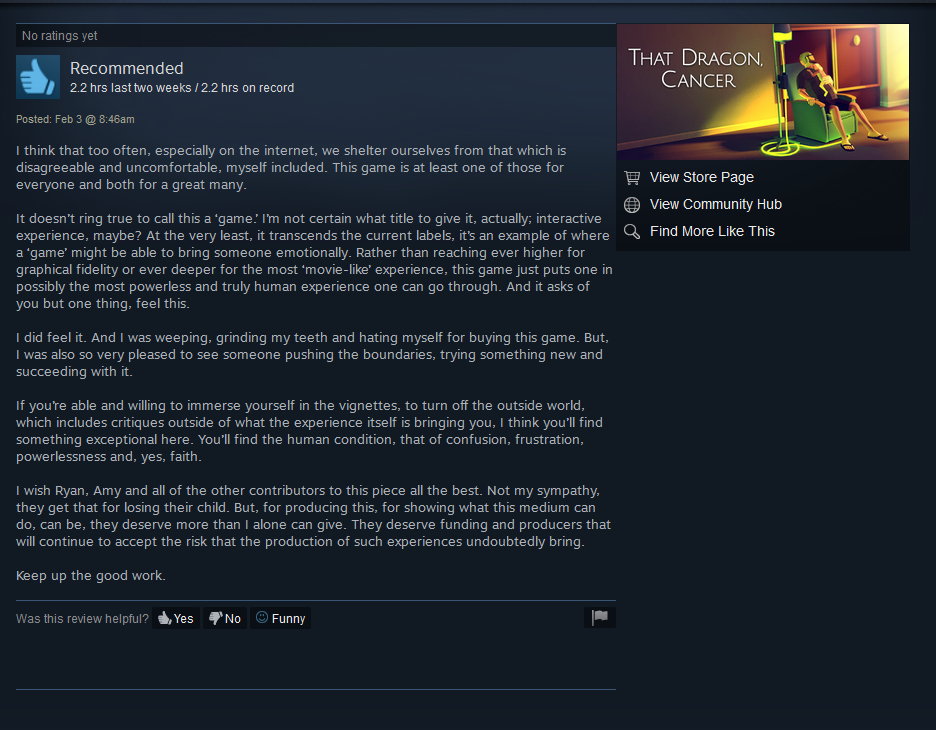

The discussion around That Dragon, Cancer right now is reminiscent of those surrounding titles like Sunset and Gone Home: that the game is crass “SJW Bait” designed to help the developers cash in on the death of their own young son. That it is nothing more than a “walking simulator” with hastily tacked on mini-game elements.

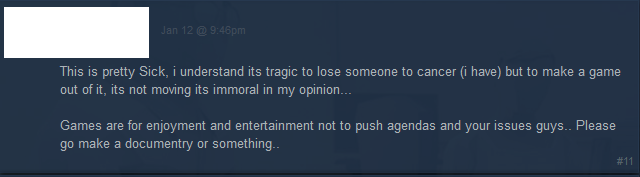

Even reviewers who enjoyed That Dragon, Cancer found themselves questioning whether or not it could be rightly called a game.

For many, this discussion is a thinly disguised kind of tribalism, a way to assert ownership of the videogaming subculture by defining what does and does not count as a “real” game.

But I think the time has come to ask the question: is “videogame” even the term we should use to describe interactive digital entertainment anymore?

According to Wikipedia, the keeper of all knowledge and the historian of the Internet,

According to Wikipedia, the keeper of all knowledge and the historian of the Internet,

The term “videogame” has evolved over the decades from a purely technical definition to a general concept defining a new class of interactive entertainment. Technically, for a product to be a videogame, there must be a video signal transmitted to a cathode ray tube (CRT) that creates a rasterized image on a screen. This definition would preclude early computer games that outputted results to a printer or teletype rather than a display, any game rendered on a vector-scan monitor, any game played on a modern high definition display, and most handheld game systems. From a technical standpoint, these would more properly be called “electronic games” or “computer games”.

Today, however, the term “videogame” has completely shed its purely technical definition and encompasses a wider range of technology. While still rather ill-defined, the term “videogame” now generally encompasses any game played on hardware built with electronic logic circuits that incorporates an element of interactivity and outputs the results of the player’s actions to a display. Going by this broader definition, the first videogames appeared in the early 1950s; they were tied largely to research projects at universities and large corporations, though, and had little influence on each other due to their primary purpose as academic and promotional devices rather than entertainment games.

So the word “video” is a technological throwback, much like calling a personalized collection of songs created for a friend a “mix tape” or describing the rollback function on a DVD player “rewinding” despite the fact that there is no longer any reels in our media to be wound. We’ve all gotten used to the moniker and so it doesn’t really bother us that it is anachronistic.

But what about the “game” half of the term “videogame?”

Here, as they say, is the rub. Many of those who were flustered or turned off by That Dragon, Cancer pointed out that the kinds of interactions players are invited to participate in are not defined by win-conditions or measurable in the form of points or achievements and so it cannot properly be called a game.

But this hasn’t stopped the videogame industry from creating products lacking these features, some of which went on to become the most popular titles of all time (Animal Crossing, The Sims). And there are tons of high profile indie games that are beloved in the hardcore gaming crowd and yet are missing game-like structures: Minecraft’s Creative mode, The Stanley Parable. Even the renowned game development auteur Hideo Kojima created one in the form of the interactive Silent Hill teaser trailer, P.T. These titles are focused on delivering stories, on enabling creativity, on reflecting on the media landscape of which they are a part, not on winning and losing.

We don’t generally hesitate to call these titles “videogames” because they involve settings and activities and aesthetics and control schemes that have become familiar to us over time as the definition of gaming expanded and different genres began to emerge. The feelings they create in us are expected and welcome, whereas those generated by a game like That Dragon, Cancer can be unpleasant, shocking, even depressing.

So, while we could decide to invent a new name for this genre, one that doesn’t feel as arrogantly dismissive as “walking simulator” (Interactive Entertainment Experience? Procedural Art?), I say that we simply allow ourselves to relax the “game” half of the definition as we apparently already have done with the “video” half. And if that means that more varied and strange types of projects come to be included under the “videogames” banner, then so be it. The willingness to experiment with new types of technology was fantastic for the games industry, enabling both better quality classically structured experiences and new forms of expression from new, independent voices. A willingness to experiment with what we are willing to consider a “game” will, in the long run, be good for gamers, too.