Running on Broken Glass

The following is a reprint from Unwinnable Weekly Issue Seventy/Seventy One, the Metal Gear Double Issue. If you enjoy what you read, please consider purchasing the issue or subscribing.

———

The opening to Die Hard is fantastic.

John McClane, perpetual badass with a sharp wit, arrives in Los Angeles to meet his estranged wife. The passengers begin unloading from the plane and our hero gets a bit of advice from a fellow traveler about how to deal with jetlag – take off his shoes. Feel the carpet between his toes. McClane lifts his arms to take out some baggage from the overhead bin and the audience and his fellow passengers are treated to a view of McClane’s gun. On his hip. On a commercial flight.

It’s a scene that’s always stuck with me.

There’s something naive and almost innocent about it. It’s like a snapshot of a happy family in a true crime story. It’s an immediate sign that this film belongs in a different era, like spotting the casual and overt racism in Breakfast at Tiffany’s or Gone With the Wind. It’s a time capsule into yesteryear and despite being the highest rated game of the year, Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain suffers from the same quaintness.

Hideo Kojima is stuck squarely in the mid-80’s.

While you murder your way through Afghanistan, Fulton-ing away the best soldiers you can find, you’re serenaded with the gentle strains of “She Blinded Me With Science.” What’s odd about this game is not its soundtrack or its commitment to the story of chief badass, Big Boss. Instead it’s that the game presents these elements without a trace of cynicism.

This critique would surely fall flat with Kojima, who as Anthony Burch points out in Metal Gear Solid, a book-length criticism by Boss Fight Books, “injects every Metal Gear Solid game with earnest if overbearing discussions of nuclear disarmament, the morality of genetic experimentation, the nature of warfare, and the difference between patriotism and terrorism.” This is a man who earnestly begins an episode of Phantom Pain with a discussion about child soldiers in Africa. There’s a clear intent to catalogue the horrors of war within the game. Grittiness is pushed through in every syllable of Boss’s dialogue, in a world overrun by terrorists and guns for hire.

This critique would surely fall flat with Kojima, who as Anthony Burch points out in Metal Gear Solid, a book-length criticism by Boss Fight Books, “injects every Metal Gear Solid game with earnest if overbearing discussions of nuclear disarmament, the morality of genetic experimentation, the nature of warfare, and the difference between patriotism and terrorism.” This is a man who earnestly begins an episode of Phantom Pain with a discussion about child soldiers in Africa. There’s a clear intent to catalogue the horrors of war within the game. Grittiness is pushed through in every syllable of Boss’s dialogue, in a world overrun by terrorists and guns for hire.

So why does it all feel so terribly silly?

It’s in its wide eyed sincerity that Metal Gear Solid V ultimately falls a bit flat. There is a terrible earnestness to Kojima’s work. He desperately seems to want you to care about his gruff heroes and the hounds of war, but he seems unaware of the other elements of his work. He has a half-naked woman who gets her energy from photosynthesis and a character whose name is basically Gun Cat. In the era of modern cynical media, this feels like being slapped in the face by a cold fish. Metal Gear Solid V sabotages its own depth by playing everything straight, by presenting real world horror alongside events no less ridiculous than, say, a humpback whale made of fire eating a helicopter. The premise would be hilarious if it weren’t so earnest.

It’s no secret that Kojima was inspired by film. His work utilizes the tropes of the hyper-masculine action film, a genre which has fallen into self-parody in recent years with flicks like Crank and The Expendables franchise, but it does so without humor or irony. It challenges nothing, and in this way it feels most at home with the Stallones and Willises and less with a AAA production in 2015.

Compare Metal Gear Solid V to something like Rick and Morty. The animated series, now running its second season, is what would happen if Doctor Who and Doc Brown had a demented, alcoholic love child. It’s unabashedly “wacky,” self-aware to the point of fourth-wall breaking asides and fully prepared to kill off its entire cast for a bit. Yet it utilizes the tropes of comedy animated series and its established pattern of assholes to bring truly honest moments of introspection and emotion. I’ve been genuinely shocked by moments in Rick and Morty, sat down and thought about characters interactions and the feelings that they actually have with one another.

Compare Metal Gear Solid V to something like Rick and Morty. The animated series, now running its second season, is what would happen if Doctor Who and Doc Brown had a demented, alcoholic love child. It’s unabashedly “wacky,” self-aware to the point of fourth-wall breaking asides and fully prepared to kill off its entire cast for a bit. Yet it utilizes the tropes of comedy animated series and its established pattern of assholes to bring truly honest moments of introspection and emotion. I’ve been genuinely shocked by moments in Rick and Morty, sat down and thought about characters interactions and the feelings that they actually have with one another.

In an AV Club interview with the writers of Rick and Morty, before Season 2 began airing, Dan Harmon said:

There’s almost a kind of will-they or won’t-they going on with Rick and Morty. Does he love Morty? Would he take a bullet for Morty? Does he care? We alternatingly indicate that he does, but then we undercut.

It’s a play on the established scientist and companion character tropes in the science fiction universe. Do you question whether the Doctor cares for Rose Tyler? Maybe whether or not he’s sexually interested in her, but you’d probably never stop and think that he might let her die so he could go play videogames. This subversion of expectations is part of the strength of something like Rick and Morty. It leaves you expecting Rick to choose the path less favorable, so that when he does something good or right, you’re oddly moved.

This kind of interaction is absent from Metal Gear Solid V. Kojima wants you to take a man named Gun Cat seriously, has soldiers talk about the main character like a 1980’s god of war and doesn’t present any of this with an awareness of its own dissonance. That’s what’s lacking in Metal Gear Solid V: self-awareness. It’s almost as if the developers feel that if they package the game with enough serious content – an audio rape log, a feature of Metal Gear Solid Ground Zeroes, for example – they can still claim to have a serious game. Even if several aspects of the game’s story are frankly ridiculous.

However, that’s not the case. These serious features come off feeling mishandled when dealt the same sincerity as other, pretty horrifying concepts. When Rick and Morty deals with an attempted rape in the season 1 episode “Meseeks and Destroy,” they do so with a great deal of honesty. Justin Roiland, creator of the show, described planning out and implementing the scene, which is pretty harrowing for a cartoon show:

I was just like, “This needs to feel like a scene from a Jodie Foster movie. It can’t be jokey. It needs to be feel really straight and dramatic and horrifying because it is. It’s a horrible thing. It’s such a jarring and unexpected twist in the story.

Tone is one of the strengths of cynical media like Rick and Morty. They’re self-aware enough to know that the same tone that they use to describe popping into Morty’s math teachers mind to change some grades is not the one that they should use to describe child rape.

Tone is one of the strengths of cynical media like Rick and Morty. They’re self-aware enough to know that the same tone that they use to describe popping into Morty’s math teachers mind to change some grades is not the one that they should use to describe child rape.

Kojima, however, isn’t self aware. By treating everything as serious and deserving of our utmost emotional attention, he makes everything insincere. The tropes on which Metal Gear Solid V is built have long been shuttered and shattered because that’s the nature of tropes. Once used so much that they become tropes, storytelling device lose meaning unless challenged. Since Kojima doesn’t so much challenge them as lovingly caress them, we are left unchanged in the wake of his “seriousness.”

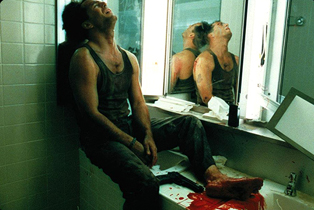

Even Die Hard knew that if you had a hero jump across a floor covered in glass with bare feet, you were going to get a bit bloody. Metal Gear Solid V just wants us to keep running.

———

Amanda Hudgins is an evangelist for Kentucky Games, founder of Storycade and occasional writer.