Interview with Alex Preston, the Creator of Hyper Light Drifter

Editor’s Note: This interview was edited for clarity and length.

–

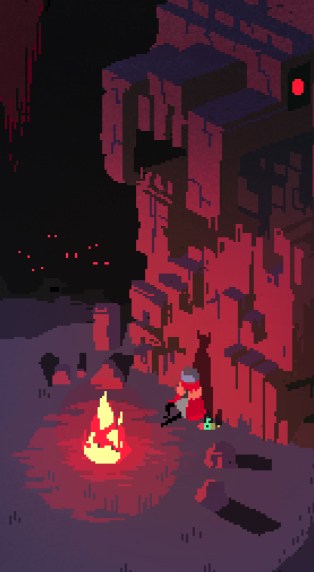

Hyper Light Drifter is a gorgeous action-RPG with a fantastical pixel art aesthetic currently in development by Heart Machine, a development studio led by Alex Preston. The game gained a lot of attention back in September of 2013 during its Kickstarter campaign when it blew past its original goal of $27,000, eventually raising a staggering $645,158. This bigger budget meant that the team could increase the scope of the project and bring it to more platforms, forcing them to shift the release date around a bit. Eventually they settled on Spring of 2016.

I recently spoke with Alex about Hyper Light Drifter, asking him about what it’s like to work on a game under the microscope of his Kickstarter backers, about the process of sharing his work with a team of developers, and the challenges of designing a game without any text or voiceover.

TM: In earlier interviews [about Hyper Light Drifter], you mentioned that The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past and Diablo were your primary inspirations in terms of gameplay, does that sound right?

AP: Yeah.

TM: Since you’ve been developing the game for several years, has your vision of the game changed over time or have you maintained a pretty consistent focus on that gameplay style throughout?

AP: I think it’s been relatively consistent. I think what happens naturally in games development is you figure out what things on paper don’t really work in the game itself that you’re building, or don’t work as well and so you change it, or you shift it, or you move it to a different point and it kind of evolves into something else or slightly, again, shifts a little bit. For the most part, we’ve stuck to the original vision, I would say, [but] all sorts of things happen during development and you figure out better ways and better solutions as you go.

TM: Is there anything specific thing that you had thought about implementing that just totally didn’t work out when you actually got to it?

AP: Uh, we originally had a shield in there way back when, and we got rid of that thing. We spent a good solid, like, month, really tackling that thing and it just didn’t really work with our game, because  it’s fast-paced, and there’s a lot of things happening at once on the screen at times, and your character is very small, and with the amount of enemies having this shield activation just wasn’t gelling with the flow of our combat and the pacing and the style of our game, so I was like, well okay, let’s drop it, let’s kill the shield. We tried a lot of different things. We really dug into that because I was convinced that we needed a blocking mechanic in there, but it didn’t really work out and it was for the better, ultimately.

it’s fast-paced, and there’s a lot of things happening at once on the screen at times, and your character is very small, and with the amount of enemies having this shield activation just wasn’t gelling with the flow of our combat and the pacing and the style of our game, so I was like, well okay, let’s drop it, let’s kill the shield. We tried a lot of different things. We really dug into that because I was convinced that we needed a blocking mechanic in there, but it didn’t really work out and it was for the better, ultimately.

TM: Once you had your Kickstarter funded, is that when you brought on additional people to work on your game or did you have them with you before that?

AP: It was just Beau [Blyth, developer of Samurai Gunn] in the beginning and Rich [Vreeland, composer on Fez and It Follows], he had agreed to do music for it early on but I think, after October it was? Yeah, October, I brought the rest of the team together.

TM: I think you mentioned in another interview that you said before working on this game, a lot of your art had been kind of personal and you didn’t really share it with other people. Once you had other people working on the game, was that a difficult process to open up your art-making to other people, or did it come naturally? Was it a supportive environment?

AP: I think because I trust the people that I work with, and because this is a project, we are all working on, it was much easier to share that stuff. Some of the things in it or aspects of the game are still pretty personal, but the reality is, well, if you’re not sharing and if you’re not opening up to the rest of your team, you’re making the process harder for everybody, so it’s been relatively easy to share the experience with everybody because this project is all of ours now.

TM: What about dealing with the public? Has that been difficult? Because you’ve had to shift your release date back a few times and, you know, obviously since you’re working through Kickstarter, you have accountability to the people who are funding you and to the people who want to play the game. Has that been difficult to deal with people who are constantly on your case, or does it keep you motivated?

AP: I think it’s a little bit of both. I think it can be difficult because it is a lot of responsibility. But it can also be really motivating and really uplifting too because there are a lot of really great supportive people out there that have been into the project since the beginning and have stuck with us, so regardless of whatever naysayers are out there, cause there’s always gonna be that subset of people in any given environment – so, you can ignore that stuff, you can choose to engage or not. You can be as pleasant or as mean as you want, but for me, I choose to focus on the more positive aspects of it, and engaging with people that actually care is genuinely a really nice thing to have every once in awhile. It’s been a positive experience overall. Doesn’t mean that it’s not stressful or that it’s not a lot of responsibility, but it’s overall been good.

TM: I imagine the way in which you spectacularly blew past your funding goal was a probably a pretty reassuring first step.

AP: Yeah. I mean, it’s a huge reassuring first step. Can’t get a better one than that.

TM: Right. Shifting gears just a bit, in terms of designing the game world itself, you’ve mentioned there’s not going to be any voiceover or text on the screen, so I imagine that you have to do a lot of storytelling and world building through the way you design the environment and things like that.

AP: Yeah.

TM: So what kinds of challenges has that presented in terms of not being able to have voiceover or text, because I imagine that people will probably be interpreting what’s happening on screen in different ways since you’re not explicitly telling them. So how do you see the world [of Hyper Light Drifter]? Do you have a strict plot in mind that you’re trying to communicate or do you kind of just want people to spend time in the world and make their own conclusions?

AP: I think both aspects of that are something that we want to touch on cause, sure, we do have a very thought-out plot and arc for the story, and there’s a lot of backstory that we don’t tell people- Like, we’ve developed quite a bit of lore internally, building this world, cause I think that’s necessary to have something vibrant that people are intrigued by, otherwise it’ll be pretty flat and the fact that we don’t have any text, or don’t have any voicework to really expand upon that, like, the world has to maintain some interest, so I hope we’ve achieved that through the visual design that we’re doing and through some of the level design stuff.

The biggest challenge… you know, I’ll give you an example. Just today we were talking about teaching people certain functions, and there’s mechanics in our game that can be relatively esoteric, and the best way to do that usually in a game is just blurt some text on the screen, remind a player, like “Hey, look,” for example, “you can fast travel,” but in our game we can’t tell people that with text so we have to find a different way to do that, and that requires more effort from us, mentally – and then also, just with the programming department and art department and all that stuff, so it’s an extra process when you don’t have that tool available and that tool is really crucial in some games, and even in our game there are times when I’m like, “I wish we had text cause it would make stuff a lot easier.”

TM: [laughs] Right, so that was kind of a self-imposed limitation, right? That was just a design choice you made early on?

AP: Yeah, early on. I think the first core meeting that we had with the five people at the center of this, myself included, we decided that was one of the vital things we wanted to make sure we adhere to from a design point. No text. Don’t do it. We don’t wanna do it. But it turns out that’s a very difficult challenge that we’ve imposed on ourselves, but ultimately I think it’ll be worthwhile because there’s something about that lack of text that transports you to a different space. There have been times where we cheat a little bit and just for internal development we put some text on the screen or whatever and it’s like, “Oh I don’t wanna see that. That doesn’t belong here.” It makes the world more coherent. You’re exploring a completely different space so when you start to put English or you know, recognizable text on there it kind of detracts from that experience a bit.

TM: Are there other games that have been doing that kind of more environmental storytelling, like no voice over, no text, that you kind of looked to or got inspiration to do that idea from or was that just something you chose early on?

AP: Yeah there’s a couple of very good examples. I mean Shadow of the Colossus did that really well for the most part. I mean, they did have some voiceover and text in the cutscenes between bosses and stuff, but it kind of built its world, and same with Ico. Like, it built a lot of its world and stories by you just observing and the situations they put you in. And it supported that through plenty of cutscenes, but it was strong throughout like, “Oh okay, I’m doing these puzzles, I’m guiding this girl. What is this statue? What is this enemy? What is this thing?” It didn’t over explain stuff.

Even Dark Souls, this whole Souls series to an extent, you know, there’s plenty of cutscenes in there and plenty of explanatory text, however, there’s just as much obscure stuff that makes you really interested. And then, Journey being one of the more recent examples that just had no text at all and no voice. Granted, that’s a simpler game, it’s not like an action-RPG or anything, but it was very beautiful in its simplicity and its presentation and you understood their point, and you understood what you could of this world that they had crafted without any text, and that made it a much more beautiful experience.

TM: You mentioned Dark Souls. I think you said that you like respecting the player and not thinking that you need to hold their hand throughout the whole process. How do you find that line between making a game accessible to people, but also not holding their hand throughout the whole process?

AP: A lot of playtesting. And a lot of, this is a bit of a pun, but a lot of soul searching I guess. You have to figure out where you personally want to draw

that line and where you feel comfortable with how games treat you as a player and then kind of reciprocate that back and put that into your own game and say, “Okay, well, how would I feel in this situation as the person playing this game?” And if I feel like it’s bullshit, then, okay, that’s bullshit and I have to change it. But if it seems fair enough or like, “Yeah, I could get that,” then I’ll implement it that way. But it’s, I dunno–you have to get introspective about it. You have to take a step back, observe things from a player’s standpoint and from your own personal standpoint and drill into the whys and  the hows, like, “Why does this bother me?” and, “How can I teach this lesson?” or, “How can I make this better or even more interesting?” So, if you can answer those questions honestly I think then you’ll find where the line is for you.

the hows, like, “Why does this bother me?” and, “How can I teach this lesson?” or, “How can I make this better or even more interesting?” So, if you can answer those questions honestly I think then you’ll find where the line is for you.

Certain people have different tolerance levels, you know, having done a bunch of playtests certain people are like, “Well why can’t I do this?” or “Why don’t you explain that?” or “I wanna save every five seconds,” and it’s like, well, that’s not our game and you have to let that go and you have to know that you will have an audience. What is your audience, you know? Identify that audience and be comfortable with that audience cause unless you’re trying to do a Minecraft or a Disney Infinity, it’s not going to be a game for everybody, cause it’s a hard game, and you have to own up to that and embrace it. Otherwise you’re going to get some mishmash hodgepodge thing that’s like, “Okay, well we’re kinda doing this and we’re kinda doing that,” and it won’t satisfy anyone at that point. I don’t wanna water down the experience and I think the Souls games are a good example of owning what they are and not being apologetic about that. Our game’s not as brutal as that but it’s still a hard game. It’s a pretty hard game, and I don’t think we need to be apologetic about that in any way.

TM: I think that about wraps up all the questions I have. Thanks so much for talking with me.

AP: Thanks Tim.