Four Dollars an Hour

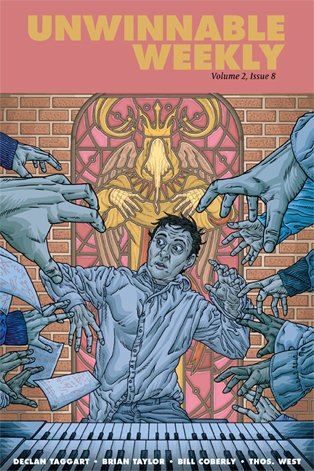

The following is a reprint from Unwinnable Weekly Issue Sixty. If you enjoy what you read, please consider purchasing the issue or subscribing.

———

1.

My worst minimum-wage experience: standing, for ten-hour stretches, by a conveyor belt on a farm in the southwest of England, watching just-disinterred potatoes go by, and reaching down to throw certain ones into a midden filled with belt mud clumps, worms and potatoes that had rotten in the ground.

My best: a factory for incontinence undergarments, where my boss cracks up one day and says, “I’m sorry…I just remembered that everything we do here…is about poo.”

My weirdest: an online bookshop’s warehouse, where you could work overnight shifts to make up your lost hours, alone, in a creepy, isolated business park. It was an odd place: over a five year period at least two employees, unbeknownst to most of the other staff, started living, at least part of the time, in the warehouse. You became used to unexplained noises. One night, alone in the front office, I heard a car stop outside, turn off its lights and idle the engine. Not knowing who it might be, I sat there in the dark, afraid to move, unsure whether to turn off the lights, trying to remember whether I’d locked the door, trying to work out what entity was outside, what they wanted, which of us was waiting and for whom.

2.

This last scenario will be familiar to anyone who played Scott Cawthon’s Five Nights at Freddy’s. For those who have forgotten, the player is confined in the security office of an off-brand Chuck E. Cheese whose animatronics roam the building at night. Should these machines chance upon you, they will shove you into a ‘costume’ designed for a narrow metal exoskeleton, not your living, squishy human body

This scenario is absolutely terrifying. Cawthon has released three sequels in the past year, tweaking the mechanics and expanding the mythology.

This is not exactly a retrospective. The term ‘post-mortem’ being unavailable, why not call it an exhumation?

3.

In the early days of the coin-op arcade game, a certain subgenre developed wherein the player mimics a real-world job and tries to accomplish certain real-world conditions. The losing state consists of the player getting fired. You might have played Midway’s Tapper, in which you stand screen right and try to send drinks screen left in some maximally efficient way. Keep a customer waiting too long, you die. In the quasi-sequel Timber, you’re a lumberjack. In the Atari 2600 Pressure Cooker, you’re a short-order cook. In Cakewalk, you’re a fancy baker. In Zoo Keeper you’re, er, a zookeeper.

In the early days of the coin-op arcade game, a certain subgenre developed wherein the player mimics a real-world job and tries to accomplish certain real-world conditions. The losing state consists of the player getting fired. You might have played Midway’s Tapper, in which you stand screen right and try to send drinks screen left in some maximally efficient way. Keep a customer waiting too long, you die. In the quasi-sequel Timber, you’re a lumberjack. In the Atari 2600 Pressure Cooker, you’re a short-order cook. In Cakewalk, you’re a fancy baker. In Zoo Keeper you’re, er, a zookeeper.

This putative genre, which sat defunct through much of the 80s and the entire 90s, rose, zombie-like, a generation later once casual gaming became “A Thing” – think Diner Dash (2004) and the following decade of time management successes.

It’s against this context, just about a year ago, that Scott Cawthon released Five Nights at Freddy’s. Though the game’s aesthetic felt just dated enough to be timeless, its early CD-ROM era pre-renders belong to a videogame past not yet mined for retro cachet.

4.

When Five Nights came out, many claimed it worked in spite of mechanics that were sloppy or hacked-together. To summarize these mechanics: the player is in a room; there are doors at both sides; the player can close the doors or turn on the lights outside these doors. This is the extent of the player’s ability to impact their environment: four on-off switches.

There are two counters: time, progressing from midnight to six am (win state), and power supply, decreasing – rapidly when doors are closed or lights are on, otherwise slowly – from 100% to 0% (losing state). The player can also look at security cameras displaying feeds of the other rooms of the restaurant. Lastly, they can look from left to right inside the control room.

There are things moving around in the other rooms. On the first night, the player forms a thesis. The things move, but not when I am looking at them. It appears there is no movement animation. I am safe in the control room if I look at the camera, even if the doors are unlocked, because they cannot get in while I am looking at them.

5.

There’s obviously something a little odd about the phenomenon of making a game out of something most often thought of as tedium. I’d like to claim that anyone raised on videogames, should they take a certain sort of repetitive, blue-collar job, will find themselves making a videogame of it in their head. I’ve worked on assembly lines before and, by the second hour, a certain dissociation sets in: the physically present body – that puts a thing onto another thing, repeats, waits for the next batch of things to arrive – becomes alienated. I start to find myself thinking of this task as unreal and setting myself sub-tasks, awarding myself imaginary badges, as it were. The real horror, though, isn’t in working a minimum-wage job that’s like a game, but in playing a game that’s like a minimum-wage job.

6.

The player of Five Nights will have to revise their initial thesis night by night. Note that this section contains fairly substantial spoilers. On night two, the player will probably lose their shit, observing in one of the cameras something move very quickly. They will then, in all probability, die. On night three, the player will assume that they only have to close the doors before they look at the cameras and they will then discover that the doors can jam. Then they will die. On the next night, they will continue to believe that as long as they are looking, the only thing that can get them is the one that moves and then they will find that sometimes another thing was moving all along. Then they will die.

This is a frustrating learning process.

7.

A digression, here: you’ve all played Bioshock, right? How about the terrorist mission in Modern Warfare 2? What about Spec Ops: The Line, a game Brendon Keogh called ‘the post-Bioshock shooter’? He is talking about what these games have in common – the ability to undermine the idea that the player is, on a narrative level, making meaningful decisions. In Bioshock, we’re told that we were under hypnotic suggestion all along. In Modern Warfare 2, we are forced to take part in the murder of civilians, or at least stand by while it happens. In Spec Ops – whose developers, one supposes, played the Modern Warfare mission and thought, “sure, we’ll run with that” – we find we are unreliable narrators with innocent blood on our hands.

It’s interesting that these critiques of agency have become more numerous as the amount of meaningful decisions made in standard shooters approach zero. Back in 2007, even, Kieron Gillen defended Bioshock, saying that it could be a fun playground while at the same time being a game-on-rails making a self-aware critique of games-on-rails. “But players aren’t all – in fact, I suspect most aren’t – wired to have fun in a world just because the tools are neat. They need to be pushed into doing neat things.”

8.

The player of Five Nights has, by now, worked out how to survive the later nights: count to six; check left door; check right door; check right near camera; check fox; close camera; count to six; check left door; check right door; check right near camera; check fox; close camera; repeat; hope. The player notes that what he is afraid of, on the level of plot, is literally being made into a mechanical thing. The player notes that he has, in learning how to play the game, mechanized himself. The player notes the irony, tiredly, as he holds out on checking the door a breath too long: finds it jammed, swears under his breath, brings up the camera, puts it down, then dies.

9.

I started teaching last year. It’s often a depressingly exploitative process, similar to the sort of work I’ve spent most of my twenties doing, but, on a good day, it provides great validation.

I hope this next part is uncontroversial. Teaching is a set of problems to solve. So is looking at a pick list and packing diapers into a box, if it comes to that, but the latter problem has one solution and few ways to succeed. With teaching, you get to fuck up, make mistakes, recover, try and draw some comedy out of it, whatever. There are days it goes terribly and I’m lethargic and depressed and I long for the comfort of a good old assembly line job. On the other hand, I never long for a pastime that feels like one. There is something very saddening about playing a videogame in which one finds oneself thinking: “Yes! I am packing these diapers so efficiently!”

10.

The claim I’ve been dancing around is that Five Nights is making the same critique of “games-as-Skinner-boxes” that we’ve seen in the shooter genre for the last decade or so. Where Five Nights differs is in making itself an explicit critique of games as capitalist leisure.

Compare the career-building of Diner Dash and other time-management peers to the famous bathos of Freddy’s ending, in which, following a single shot of your ridiculously small paycheck, the executable quits.

Even though Cawthon’s later entries in the series have thrown much of this potential away, it remains the most existentially disturbing rimshot gag in gaming. Is that all there is to this, thinks the player. Is that the best I could do?

———

Thos. West is a struggling artist and/or poète maudit whose earliest memories include being deeply perplexed by Lords of Midnight on the Spectrum ZX. He lives in South Korea and tweets very, very occasionally at @thomp.