Who Watches the Watcher

The following is a reprint from Unwinnable Weekly Issue Eighteen. If you enjoy what you read, please consider purchasing the issue or subscribing.

———

Danny St. John wants to eat you alive. He attacks you in his family’s barn with a shotgun. You fight back with any farm implement you can get your hands on. Finally you knock him down, hold him, at hoe point, on the ground.

This is near the end of the second episode of The Walking Dead’s first season, where your band of survivors happens upon a family desperate enough to resort to cannibalism. Fifty-five percent of people who played chose to kill Danny.

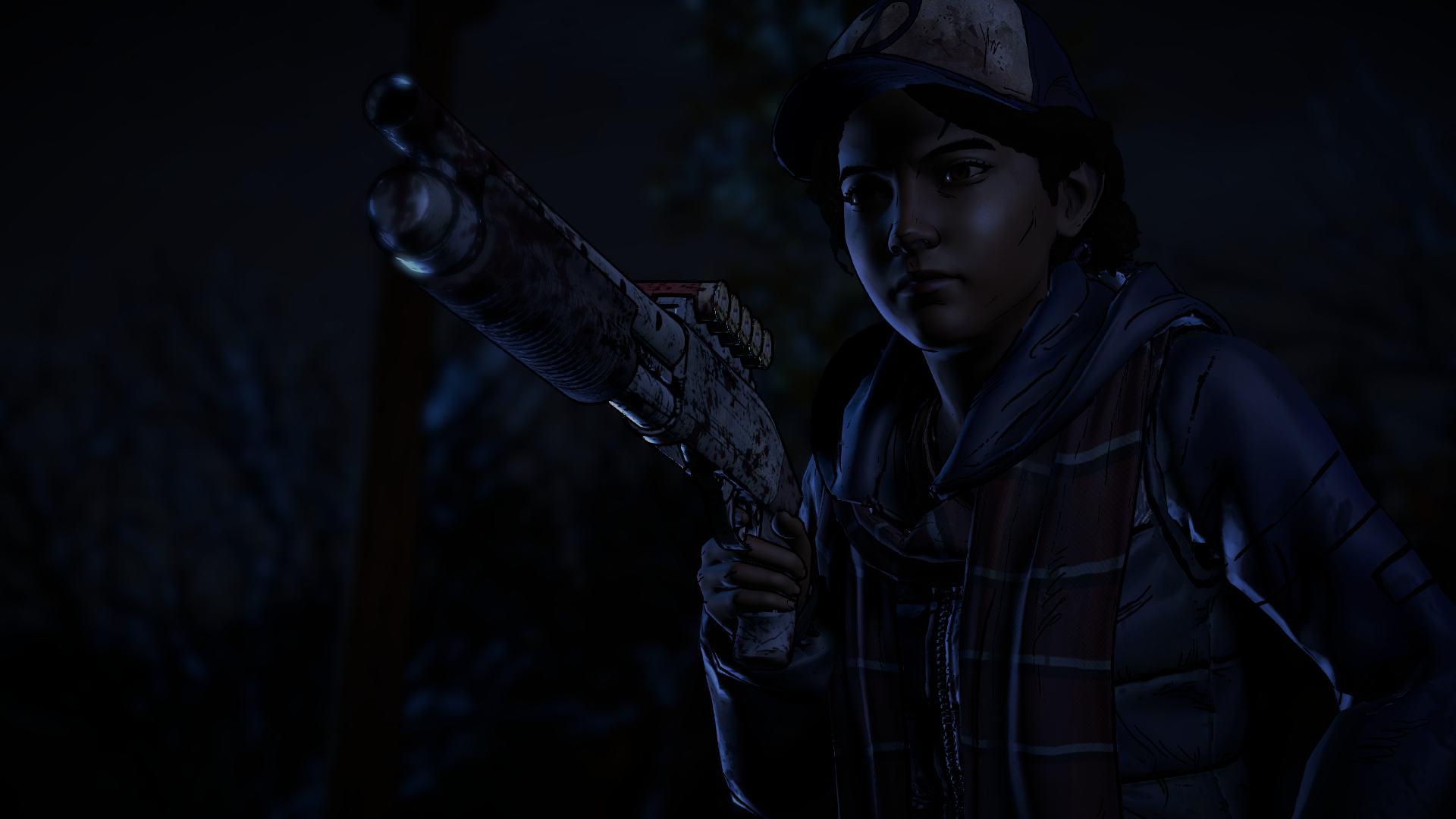

But if you kill Danny – you being Lee, the protagonist of the game – the camera jump cuts to a close-up of Clementine, the young girl that Lee has promised to protect. When Danny dies Clementine screams and recoils in horror. The screen, if environmental hints are enabled, displays the words “Clementine witnessed what you did.”

Moments later, players must make a similar choice about Danny’s equally sadistic brother Andy. Once again, Clementine is watching. Only 20 percent of players killed Andy.

In The Walking Dead, players’ main goal is Lee’s – and Clementine’s – survival. Clem is the driving action of the plot, the “motivator” for players to continue playing and making choices along the game’s branching narrative paths. Nearly every action players can take: killing someone, sparing someone, speaking kindly, speaking harshly, these are all arguably all motivated by a desire to keep Clementine from witnessing the horrors of the world. Players can decide which choices they will make in order to subjectively fulfill that notion.

Your choices don’t happen in a vacuum. Other members of your party of survivors all have strong opinions about Lee’s (i.e., your) decisions. They all want Lee to act a certain way and your opinions of these characters may influence your decisions as Lee. Clementine is among these opinionated characters, but she’s different from the rest.

Unlike some of the other survivors – unstable or flighty or reserved as they may be – Clementine is consistently portrayed as kind, affectionate, innocent, willing to defer to the player’s decisions but always able to make her displeasure known when you do something she would consider bad. Because of this, Clementine’s opinions about your choices are coded differently than anyone else’s. Given Walking Dead’s construction of narrative choices, Clementine is not only a motivator: she is your moral compass.

Unlike some of the other survivors – unstable or flighty or reserved as they may be – Clementine is consistently portrayed as kind, affectionate, innocent, willing to defer to the player’s decisions but always able to make her displeasure known when you do something she would consider bad. Because of this, Clementine’s opinions about your choices are coded differently than anyone else’s. Given Walking Dead’s construction of narrative choices, Clementine is not only a motivator: she is your moral compass.

That isn’t to say she outlines the single “correct” or “good” path players must choose to succeed. Instead, Clementine acts as the motivation for you facing those decisions in the first place, rather than necessarily acting an influence on whatever choice you pick. Still, there are times – as with the St. John brothers – that Clementine also becomes an active moral guide for steering players toward decisions one would code as “kinder” or “more merciful.”

Moral compass characters are common in videogames, and more often than not they are female. On its surface, the inclusion of female nonplayer characters appears to be an effort to increase diversity, but in many ways it continues to play into the established convention of the (often morally gray) male protector who must do right by an (often younger) female character.

Examples include BioShock Infinite’s Booker and Elizabeth, though because Infinite has a linear story, Elizabeth’s moral influence doesn’t influence players’ in-game choices. Rather, her moralism compounds her role as motivator, keeping players engaged with the story.

Joel and Ellie of The Last of Us also offer a variant of the device, though in this case Ellie’s survival for its own sake isn’t the entire motivator – she may hold a cure for the pandemic that has stricken the world. (Joel is also eventually motivated to commit acts that one might consider amoral instead of moral, though still for Ellie’s sake.)

Telltale even uses the same idea in its game The Wolf Among Us. As Alexa Ray Correia noted in an article for Polygon, a variation occurs in a scene where the player, Bigby Wolf, must interrogate a suspected murderer while his ladyfriend Snow White watches. The more Bigby uses violence to get the answers he needs, the more Snow White clearly disapproves.

“And as we struggle with Bigby to retain his humanity despite dealing with some truly despicable characters, we measure his success in keeping it against Snow’s reactions,” Correia says. “She is our moral compass, our barometer for how much of Bigby is left. We see ourselves through her eyes.”

In its use of Clementine and her gaze as a moralizing force, The Walking Dead deploys a motif common to many other American decision-based RPGs.

Everything changes in The Walking Dead’s second season.

When the game picks up from the end of Season One of The Walking Dead, the player is now controlling Clementine. Unlike Lee, whose goal to protect Clementine was clearly defined, Clementine herself has no such mandated allegiance. The scripted “motivation” to continue playing is to keep Clementine alive – nothing else.

Without another character to motivate her, Clementine also has no one “moralizing gaze” to influence her decisions. In The Walking Dead’s first season, Lee had the ability to put Clementine’s needs above any other character’s, and the assurance that he was correct in doing so. In Season Two, Clementine does not have that privilege. It completely throws out the notion of the moral compass character.

Instead, throughout the game Clementine must weigh the desires, values and goals of several different characters, primarily Kenny, Luke, Sarah and Jane.

Of these, Kenny, Luke and Jane are almost always in indirect or outright conflict with each other. They constantly disagree over the “right” thing to do and they drag Clementine into the center of their arguments. None of them are portrayed as more morally righteous than the others – if players wish to side with one over the other, they must make that decision on their own, without even the suggestion of assurance that they have chosen correctly.

Sarah is perhaps the closest to the role that Clementine played in Season One. But Sarah isn’t a Clementine. Unlike Irrational Games, who were very concerned that players not feel annoyed by Elizabeth in Infinite, Telltale made Sarah naïve, fragile and unreliable. She is annoying. If you want to help Sarah, you’re going to have to work at it, and you’ll probably be miserable while you do it.

Discussion of female characters in videogames has been even more heated lately. Some people, skeptical of “diversity for diversity’s sake,” criticize the idea that adding female playable characters increases a videogame’s aesthetic or dramatic value.

Season Two of The Walking Dead is proof that a female main character is capable of exploring angles and scenarios that just aren’t open to the male characters we most often see. That’s not to say that the roughened male trying to do right by the female is inherently bad. Scenarios become motifs for a reason: they evoke powerful emotional responses from us. And as seen in Infinite, The Last of Us and The Wolf Among Us, the motif still leaves room for some variation.

But these devices can become so common that re-experiencing them feels like tracing tire-grooves in a well-worn street. We know how these things go because we’ve seen them before. Though these games may be about a man protecting a woman, paradoxically it’s the male character who is always constructed as dependent on the female character for moral and narrative guidance through the game.

The Walking Dead’s second season isn’t like that. Clementine has no Elizabeth, no Ellie, no Snow White and no Clementine of her own. The game gives you no hints as to what the morally right answers are. With no moral compass and no defined motivation other than “stay alive,” the game sets players adrift in its increasingly difficult scenarios – ones with much more compelling and emotional payoffs.

———

Jill Scharr is a former tech and games writer at Tom’s Guide, and has been writing for Unwinnable since the new Star Wars movies were announced in 2012 and she really, really had to talk about it. Currently, she is a writer at Bungie. Catch her on Twitter talking about videogames, comic books, feminism, science fiction and various combinations of the above at @JillScharr.