Dance Dance Dance

The following is a reprint from Unwinnable Weekly Issue Nine. If you enjoy what you read, please consider purchasing the issue or subscribing.

———

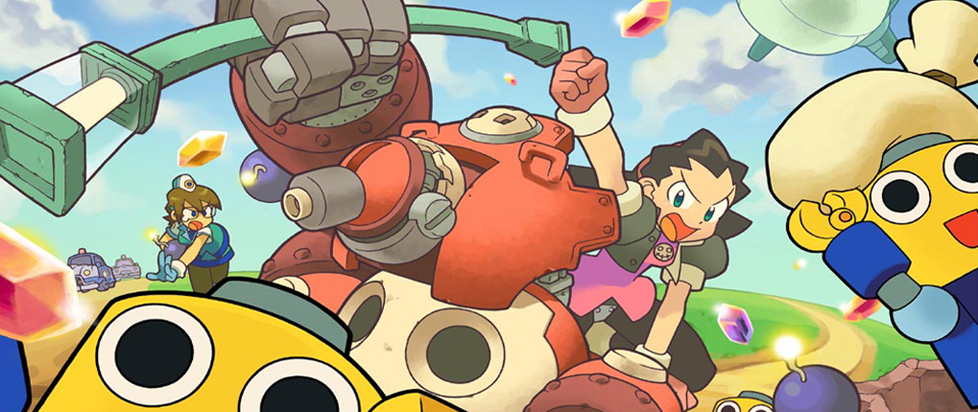

When P.N.03 was first announced for the Nintendo GameCube as part of the fabled Capcom Five – a series of high profile console exclusives circa-2003 and helmed by some of the Japanese publisher’s most prolific talent – initial descriptions presented a fairly straightforward premise.

Lone mercenary with a mysterious past? Check.

Sci-fi setting featuring artificial intelligence run amok? Yup.

Guns? Do you even need to ask?

As notable as the project was for being directed by Resident Evil creator Shinji Mikami and landing on a console starved for attention, the game – in which main character Vanessa Z. Schneider traveled through monochromatic corridors gunning down killer robots – didn’t quite make the same first impression as the colorful comic book stylings of Viewtiful Joe or the surreal, Lynchian madness of Killer7.

Consider the title: it’s an acronym for “Product Number Zero Three.” A name like that isn’t exactly inspiring. It’s one that brings to mind some of the worst thoughts you could have about videogames – that they are rolled out one after another, off an assembly line, merely as items for consumption rather than for your measured consideration.

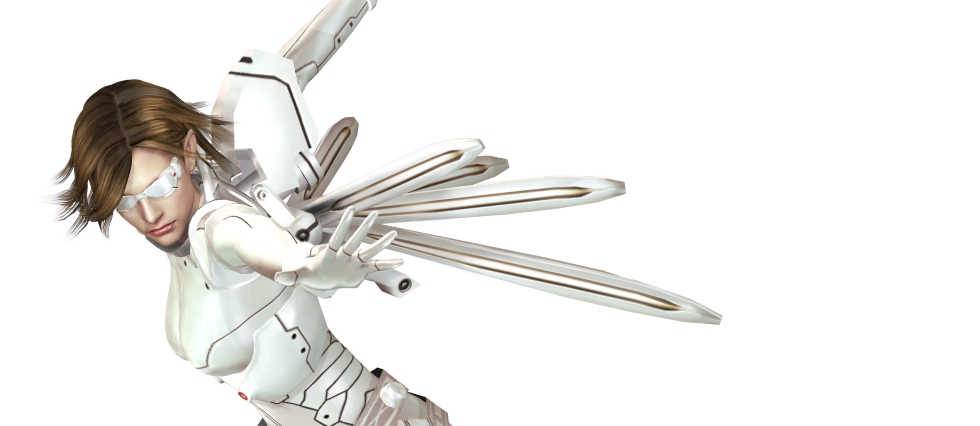

Vanessa herself could’ve easily been regarded through a cynic’s eyes as well, what with her curvaceous appearance seemingly designed to distract players from the generic nature of the rest of the game. At P.N.03’s reveal, Vanessa employed guns and enough sex appeal that people expected an adventure like Tomb Raider set in a forlorn space colony. Were it not for some changes during development, she would’ve also run and maybe jumped and aimed those guns at countless enemies, thousands of bullets spent by the time the game shipped. Surely she would have been able to upgrade a predictable set of weapons: a machine gun, a shotgun, a rocket launcher.

Thankfully, when the bright lights finally shone on Vanessa herself, she did something far more interesting: she danced.

She danced. She twirled. Her guns were removed entirely due to time constraints, replaced with powerful plasma shots that were fired out of the palms of her hands. She pirouetted as cybernetic foes unleashed bullets in her direction; snapped her fingers rhythmically to a pulsing soundtrack as she unloaded on hostile opponents. Suddenly, P.N.03 displayed a creative spark that was sorely missing beforehand.

When people picked up their controllers to harness this impressive imagery, though, they were in for a rude awakening. P.N.03 was hard. It didn’t feel right. Under the stiff control scheme, often equated with maneuvering a tank, it was like trying to control a dancer’s movements simply by shouting commands at her and watching as she staggered through your directions.

When people picked up their controllers to harness this impressive imagery, though, they were in for a rude awakening. P.N.03 was hard. It didn’t feel right. Under the stiff control scheme, often equated with maneuvering a tank, it was like trying to control a dancer’s movements simply by shouting commands at her and watching as she staggered through your directions.

What one earth was going on? Was this some kind of cruel joke?

It wasn’t the first time Mikami confounded expectations nor would it be the last. Turning well established genres on their head is a routine for the man, who did it recently for the cover-to-cover shooter with Vanquish and for the survival horror genre with Resident Evil.

In a stark and simple way, P.N.03 highlighted an undercurrent present in so much of his work. Vanessa’s story may have featured a colony overrun by machines, but Mikami’s not interested in exploring what it means to be human so much as what it feels like to be one, and that means coming to grips with something as frequently frustrating as having a body.

I’ve written about this before; one of the great things about fighting games is that they digitally capture the feeling of executing amazing physical feats with a less than perfect physical form. Watch someone try his or her hand at ice-skating for the first time, then watch someone play their first match of Street Fighter. Limbs flail and a large portion of time is spent on one’s backside, completely out of sync.

You can see the same concept hard at work in a title like P.N.03. With Vanessa, the player is constantly fighting to reduce the negative consequences of her limitations. You must manually adjust her positioning in order to have her shoot in a different direction. You can’t just tilt the joystick left and watch her run left. She must be stopped, rotated and then moved. She can’t shoot while in motion either, meaning you have to time your attacks just right in order to avoid being caught in the crossfire of the enemies. She can dodge incoming fire, but even then she’ll only twirl laterally for as many times as you push the corresponding shoulder button.

Gliding through the world with a move set like this takes work, as the clash between rigid controls and the agile, athletic play style necessary to succeed forms the core of the game. The feeling is similar to Vanquish, which does feature plenty of guns (as well as space marines), but also forces you move beyond the safety of cover and take risks before the game brutally punishes you for failing to capitalize on your actions. Stay a sitting duck in Vanquish and you die. Yet, with some effort, both these games give players the ability to coordinate their movements and improvise in any given situation, allowing them to choose the right move, like sliding a perfectly sized block into an empty gap that’s precisely the right size.

Cannabalt creator Adam Saltsman detailed this kind of design via a dissection of Vanquish, in which he exposed Mikami’s skillful layering of mechanics and systems. Saltsman noted correctly that Vanquish’s “most important” directive is to coax the player into putting on a show, what with its rock star imitating boosting mechanism, frantic pacing and dislike for all manner of protective coverings. I’m less interested in the meticulous schemes themselves, though, than the fact that we’re taking advantage of these built-in, immaculately designed systems to somehow – even if just for a moment – break free from the very structures holding us back.

Perhaps more so than any of these titles, God Hand is where this idea of interlocking parts is taken to its logical extreme. Unlike Vanquish or P.N.03, God Hand translates the classic side-scrolling brawler into 3D, but allows the player to customize virtually every part of the main character’s move set. There are literally dozens of different actions at the protagonist, Gene’s, disposal, each one capable of being assigned to any button the player wishes. God Hand is the ultimate action-game expression of how the various parts of the body can be brought into harmony, all for the sake of creating a virtuoso performance.

Although Gene is also operated by way of survival horror’s infamously wooden controls, the only measure by which you’re judged in God Hand is for how long you can sustain your extravagant fighting style against an increasingly smart enemy AI. The better, more stylish and more impressive your showpiece is, the smarter and tougher your enemies become. Flub a move or two and get pounded, and the enemies get weaker and weaker. The systems, ever present, are important, but only insofar as the player can rise above them. This works not only to defeat whatever is oppressing you, but also to completely render their hindrances a performative non-issue.

It’s a theme often explored through the method by which Mikami sets up his games’ controls, but it permeates the narratives he gives us, too. Compare and contrast Vanessa’s grace and fluidity on-screen with the predictable patterns of machines going haywire. Or Vanquish’s outlandish power ballet with the hulking robots that are destroyed. Even in Resident Evil, you’re lumbering through the mansion rotating on an axis to overcome waves of infected, diseased bodies. With Gene, you are battling demons using the divine power of God, manifest through your own form.

There’s a reason Mikami’s antagonists are rarely other people. Machines and even zombies can be programmed for certain behavior or learn new tricks, but it’s only humans that can overpower the shackles that bind them.

Some of these attributes can be found in multiple games, but so many concern themselves with ensuring players are always carrying out awe-inspiring maneuvers with ease. A Mikami outing feels different. That kind of performance is possible in P.N.03 or God Hand, but it’s harder to attain. You have to work a little more for it. It’s what has made Mikami’s work resonate with so many: that in spite of a constant struggle with outwardly unintuitive controls or our own imperfections, in a world beset by immovable structures and systems, they implore us to transcend our limitations and strive for the most beautiful display of our ability as possible.

———

Jordan Mammo is a dance machine whose moves have appeared in the likes of Kill Screen and Paste Magazine, as well as a few too many karaoke bars. Sometimes he actually plays videogames. Follow him on Twitter @jordanmammo.