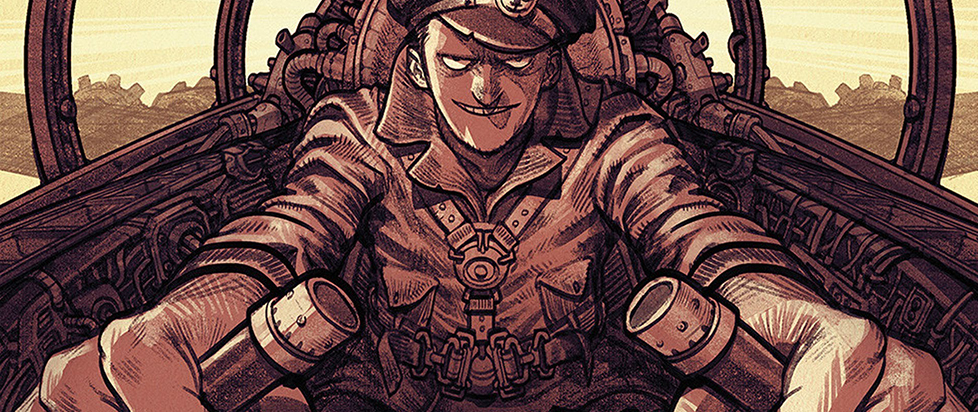

Notes on Luftrausers

The following is a reprint from Unwinnable Weekly Issue Two. If you enjoy what you read, please consider purchasing the issue or subscribing.

———

In 2010, game critic and developer Tim Rogers wrote a review of the PlayStation 2 beat-em-up title God Hand. “God Hand is like being a professional chainsaw-wielding glacier demolisher at a party where the penguins are going to need a lot of ice cubes,” Rogers writes in the first paragraph. “Though God Hand is usually like poking holes in a watermelon with a chopstick for the best reasons… [it] is sometimes like using a pizza cutter to eat ice cream,” he continues.

It’s not particularly useful advice to someone deciding whether they would like to buy a videogame like God Hand, but if you read Rogers’ review after you playing it, you kind of nod to yourself and think, you know, God Hand does feel like writing a friendly letter by hand while wearing brass knuckles, for instance.

2.

There are two people making videogames who, I think, really know how to make a game feel good: Tim Rogers and Vlambeer’s Jan Willem Nijman. They aren’t the only two people who can pull it off, but they are the two developers I trust to make a game that puts “feeling good” above all other goals. Design, rules, look, sound – all are subservient to how the game feels in that spot of the skin on the player’s fingers, that surface area that rubs against a trigger button or feels the resistance from the spring of a thumbstick.

They know that even when players and developers can’t quite describe why they love a game, it is often because of how that game feels in the hand. It’s the “sticky friction” that Rogers often writes about: Super Mario Bros. isn’t popular because it is a sidescroller, but because of how Mario felt as he accelerated and slid across the screen. It’s bodily. It’s phenomenological. We play videogames, first and foremost, because they are bodily pleasurable to engage with.

3.

This is why Vlambeer’s games are so successful. They are clever and delightfully designed with ingenuous rule sets, to be sure, but more than this they feel good. I stop playing a Vlambeer game and I can still feel it in my fingertips, like I might be able to feel a basketball long after I passed it back, or an orange long after I peeled off its skin and devoured its insides. I walk away from a Vlambeer game – I disconnect my body from the plastic hardware and my senses from its screen and speakers – and I can still feel its very physical, very real sensation in my fingertips. To talk about the experience of playing a Vlambeer game is, first and foremost, to talk about how playing that game feels as a real, physical activity with a tangible object.

4.

Flying is throwing yourself at the ground and missing. Flying is falling gracefully. I don’t remember where those quotes are from – some movie or another. Both capture the joy that is moving in Luftrausers. Luftrausers is not a game about flying; it is a game about falling gracefully. It is a game about inertia. It is the game equivalent of those action movie high-speed chases where the hero spins their car 180 degrees, shoots their pursuer in the face with a single shot, then spins the car another 180 degrees and keeps driving without slowing down. Luftrausers is about doing this over and over again, with only enough time in between to decide what direction you will fall next.

Flying is throwing yourself at the ground and missing. Flying is falling gracefully. I don’t remember where those quotes are from – some movie or another. Both capture the joy that is moving in Luftrausers. Luftrausers is not a game about flying; it is a game about falling gracefully. It is a game about inertia. It is the game equivalent of those action movie high-speed chases where the hero spins their car 180 degrees, shoots their pursuer in the face with a single shot, then spins the car another 180 degrees and keeps driving without slowing down. Luftrausers is about doing this over and over again, with only enough time in between to decide what direction you will fall next.

5.

Left, right, up, fire. This is all Luftrausers requires. All of that physical sensation evoked in your body travels through the transponder that is two thumbs against the plastic of the controller. New players or observers of screenshots compare it to twin-stick shooters like Geometry Wars, but the kinesthetic pleasure of Luftrausers is perhaps closer to Asteroids. Right and left do not propel your plane right and left, but rotate it clockwise or counterclockwise, with up thrusting you in the direction you are facing. All directions are relative to the position of your plane. The only absolute is down: that persistent gravity so central to the feel of the game.

6.

Shooting is tangled up with movement. Shooting and thrusting are both connected to the direction your plane’s nose is pointing. If you want to move in one direction but shoot in another, you must find other means of movement: inertia, momentum, kickback. Wanting to shoot and move in different directions is the heart that the rest of Luftrausers depends on.

7.

Luftrausers is a game of acrobatics and elegance. You pick up speed, pull out of a nosedive and do three backflips across the sky, dropping a bomb on a different ship below at the apex of each circle. You let go of the thrusters amidst a wall of slow-moving enemy bullets and just hang there, frozen in time and space for a millisecond as they all pass you harmlessly. You equip the spread gun and use its recoil to bounce yourself higher into the sky as you rain bullets down on your pursuers before flipping and falling back to the ocean.

8.

It’s in the art of screenshake that Nijman has written and presented about, closely related to what Steve Swink discusses as “polish” in his book Game Feel, or what Kyle Gabler has called “juiciness.” Nijman is the developer equivalent of those early rock musicians holding their electric guitars up to the amp to create ridiculous feedback loops. When you rotate your plane in Luftrausers, the camera swings around like it has been attached to the end of a morning star. You continue to move left across the screen with your last thrust, but as you rotate to face the right, the camera swings around, always keeping your plane’s tail closer to one edge of the screen or another. Thrust forward again and the plane is practically slammed against that edge of the screen, like the pilot’s head would be slammed against their chair. It’s nauseating, but it communicates an excessive amount of feedback through the simple act of rotating a thumbstick left or right then jamming it straight forward.

When you shoot, it isn’t a single line of tiny bullets that launches out but a splayed stream of projectiles larger than the plane that spawned them – not hitting enemy planes but splashing into them. Destroy a large target, like a warship or a large plane and the camera, just for a second, forgets about your plane and your need to focus on it entirely, like the morning star swinging camera operator was so shocked by the explosion they turned and looked like some damn rookie while you, the badass, are already flying on to your next target. The feel of Vlambeer games is exaggeration and amplification, not nuance.

9.

Vlambeer understands that the “mechanics” of a game are the skeleton of that game: central and vital to game design, but not the meat.

10.

I am undecided on Luftrausers scoring system. It’s simple: kill enemies fast to make the multiplier increase to a maximum of x20. Stop killing enemies and you soon lose the multiplier. It’s intent is to make the player aggressive, as Vlambeer’s other half, Rami Ismail, has explained. It creates a fascinating tension with the ingeniously simple mechanic of needing to stop shooting in order to regenerate health. It achieves the tone it strives for.

However, it doesn’t always seem to match the quality of a performance to a score. Large targets, like battleships and blimps, are killed by persistence, not sudden and wild aggression. You chip away at their health in a series of swoops and spirals. It’s excellent and exhilarating, but the time investment required means few large targets will be killed with a multiplier larger than x1.

There’s a balance to find: kill just enough small fighters to keep the multiplier up while chipping away at a big target. It never seems to quite work. Some of my best feeling games have scores under 10,000. My one game of 42,000 points was spent just attacking the small fighters, ignoring the larger targets until they eventually overwhelmed me. It’s quite possible, of course, that I simply haven’t figured out a winning strategy yet, that I am approaching it in the wrong way. I wonder, though, if Vlambeer have managed to make the game feel so good that no score can ever feel like an adequate measure of how well you feel you performed.

11.

To be sure, this doesn’t matter. Not at all. I play other arcade games for the leaderboards: Geometry Wars, Ziggurat, Super Meat Boy. I play them to get good at them and to show off that expertise. I want to master them. Luftrausers’ scoring system might be imperfect for this, but mastery is not why I have spent so many hours playing it. I play it, still, because it feels good. It transcends the need for a score or other metric to justify an engagement with it. It is a game that the simple performance of is enough. Like popping bubblewrap. Like sticking your finger in corn flour. It is a game where the sub-verbal sensations it sends through my thumbs, eyes and ears are more important than any placement on a leaderboard. The act of playing Luftrausers – of touching it – is so intrinsically rewarding that no extrinsic rewards or numbers could do the experience it offers justice.

———

Brendan Keogh is a videogame critic and academic from Melbourne, Australia. He has written for a variety of outlets including Edge, Overland, Kotaku, Polygon and Ars Technica. He is the author of Killing is Harmless: A Critical Reading of Spec Ops: The Line. Follow him on Twitter @BRKeogh.