Revving the Engine: Dead Static Drive

The following is a reprint from Unwinnable Weekly Issue Fifty. If you enjoy what you read, please consider purchasing the issue or subscribing.

The following is a reprint from Unwinnable Weekly Issue Fifty. If you enjoy what you read, please consider purchasing the issue or subscribing.

This series of articles is made possible through the generous sponsorship of Epic’s Unreal Engine. While Epic puts us in touch with our subjects, they have no input or approval in the final story.

———

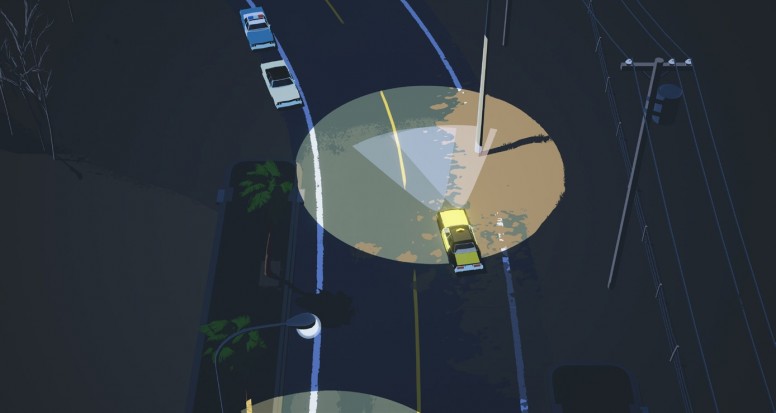

There is something distinctly American about Dead Static Drive.

The cars, for instance. Four-doors, chrome bumpers, rag tops, squared off and gas-guzzling and hefty. Michigan’s finest. My first car was a 1985 Delta ‘88 Oldsmobile – I bet the cars in Dead Static Drive handle about the same, like driving a really comfortable brick.

Then there’s the diner. Nothing says American road trip like a diner. I can use some of the same words to describe them. Chrome. Squared-off. Hefty. The neon signs and the black and white floor tile beckoning you inside for a burger and a shake.

Sure, there is horror in Dead Static Drive – the world is about to end, after all – but deep in its core, the game seems fueled by a deep American nostalgia. It comes across powerfully, even though there are only a handful of images and videos of Dead Static Drive out in the wild.

This is all the more impressive because Mike Blackney, the developer behind Dead Static Drive, is an Australian.

Born in a small country town of 13,000 souls called Sale, Victoria, the 36-year old Blackney has been on the path to game development since getting his first computer in the mid-‘90s. He’d always played games, going back all the way to the Atari 7800, but it was owning a computer that got him programming, first fiddling with Qbasic and then graduating to Basic, Pascal and C++.

Blackney worked a variety of jobs, from building websites during the dotcom boom to programming barcode scanners for plant nurseries, before landing a job at Melbourne’s Transmission Games. When Transmission closed, he moved on to smaller studio projects, including Alexander Bruce’s trippy first-person puzzler Antichamber. He currently teaches programming at SAE Qantm, a global multimedia college.

Mike took time out of his busy schedule to talk about the important things in life, like horror, Dead Static Drive and Kurt Russell.

Your Twitter handle is @kurtruslfanclub. How important is the life and work of Kurt Russell to you?

Ha!

So important. That hair. That jawline.

I used to have a Kurt Russell VHS collection, with all the classics like The Thing and Escape from New York, but also the less good ones like Executive Decision and Soldier (ech). If Death Proof had been released on VHS, I’d have totally flipped out, especially with the glitchy celluloid effects on tape.

A lot of people see my screen name and assume it’s some sort of joke (mostly, the Kurt Russell Fan Club is just one guy, geddit?) but I really love him. Even if the movie’s bad, I know if Kurt Russell is in it then he’ll be charismatic (except in Soldier) and I’ll still enjoy watching the movie just for him. And, conversely, I know if Ray Liotta is in a movie then I’ll probably hate it regardless. I don’t know why, but he’s just unwatchable. Ray Liotta is the anti-Kurt Russell.

I think there’s a wonderful thing about saying you like Kurt Russell, though – it’s implicitly saying you like Kurt Russell in John Carpenter films. I think the very best work these two did was when they worked together, with exceptions for Death Proof and They Live.

Speaking of John Carpenter, and since Dead Static Drive is a horror game, care to share your favorite movies or stories?

The first R-rated horror movie I watched was The Evil Dead when I was nine. I was so scared of the deadite under the trap door yet still so excited by being scared, I think that’s when I formed my love of horror.

For favorites, though: Texas Chain Saw Massacre and The Thing, because they’re both crammed with tension. I never expected to like Massacre because its name makes it sound cheap and gratuitous, but I think the scene when you first see Leatherface is one of the best moments in film horror – up there with the shower scene in Psycho.

For favorites, though: Texas Chain Saw Massacre and The Thing, because they’re both crammed with tension. I never expected to like Massacre because its name makes it sound cheap and gratuitous, but I think the scene when you first see Leatherface is one of the best moments in film horror – up there with the shower scene in Psycho.

For written horror: I Am Legend and Duel, both by Richard Matheson and both just amazing. And Duel made a fantastic film. I Am Legend made many average films. Both of the stories are very intimate and I love how much drama results from the characters’ personalities and flaws. Plus, they both have average, flawed characters. I love that. I love stories about likeable losers and anti-heroes.

There’s also The Hawkline Monster: A Gothic Western by Richard Brautigan. It’s a semi-Lovecraftian black comedy and genre parody that is wonderful, though not at all scary. Anything by TED Klein, especially “Petey” and “The Events at Poroth Farm.” These both riff on the Cthulhu Mythos and are supremely readable. Finally, any Edward Gorey. I love the mysterious Edwardian stories but a surprising stand out is The Curious Sofa, a sort of implied sexual romp with some great horror. There’s also a real loneliness to his work, which I think is a feeling not many authors try to play with.

You’ve described Dead Static Drive as “Grand Theft Cthulhu.” What are your horror inspirations in terms of the game?

I used to adore the original Romero zombie trilogy, but these days it’s hard to want to watch them with all the over-saturation of zombies. In the same way I think the Star Wars prequels ruined my motivation to revisit the classic Star Wars movies.

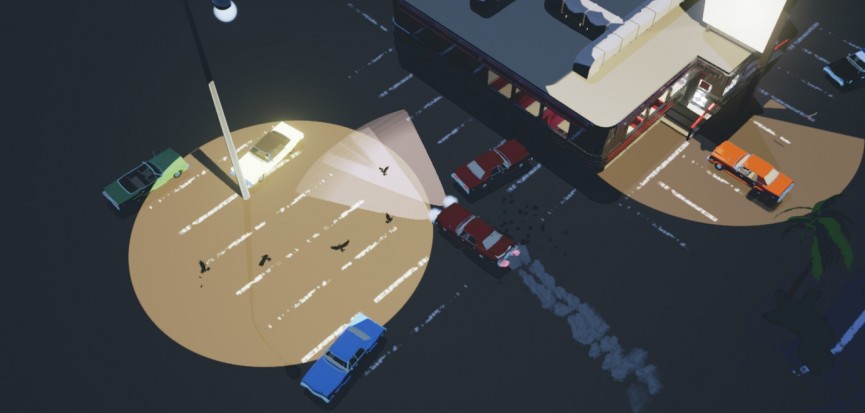

But in the original Romero films, what I always loved is how some sort of apocalypse like that would change the rules of ordinary activities – you sort of partition the world into areas that are safe and unsafe and you have to be careful performing simple tasks like rounding a corner. I think living in a world of zombies would be a lot like driving a car – I can imagine a hazard perception skill set you’d need to learn to be able to cope.

When I look at horror, I don’t want gore (though gore is fine) – for me horror is about tension, ongoing looming threats and stomach-churning revelations. The point in Dawn of the Dead when Roger is bitten and you know now he’s going to turn. Or the moment in The Ring when we cut to the male love interest in his apartment and we’ve just found out that Sadako/Samara is still going to come for him. I’d love to capture those moments in a game through the mechanics.

How did Dead Static Drive start out? What pushed it into its current form?

Dead Static Drive is the end result of a lot of prototyping and learning what didn’t work. The setting always came second to the mechanics early on, so it’s had a few states where very similar game elements existed within quite different worlds. The phrase I’ve always used for the philosophy behind the game is “meaningful exploration,” and failing to hit that is why I’ve had a few wildly different prototypes.

The original spark was called Creature and started as an open-world 3D game. A big part of the game was building your own vehicles, but when I prototyped it, the building mechanic was one game while the travel and exploration was another, and they weren’t totally compatible. Building and customizing your vehicle demanded more focus on competition and collaboration with other players. That started taking me away from the core goals.

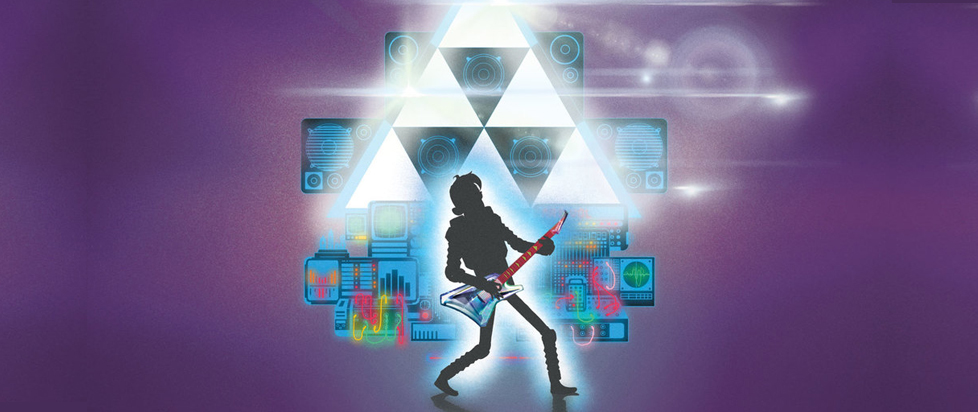

I should mention that I was using my own engine, writing it in C++, so I was constantly struggling to make new tools as I designed the game. I cut back on the scale of the game to compensate, and that’s when I designed it to suit a space themed prog rock album cover, now working under the title Kreature. I made the concepts and prototypes and transitioned to Unreal.

I should mention that I was using my own engine, writing it in C++, so I was constantly struggling to make new tools as I designed the game. I cut back on the scale of the game to compensate, and that’s when I designed it to suit a space themed prog rock album cover, now working under the title Kreature. I made the concepts and prototypes and transitioned to Unreal.

This was just after UE4 came out and getting to work with C++ meant it was a no-brainer to move from my own engine. I loved this game concept but somewhere in the style shift from 3D to 2D I’d taken away too many of the exploration decisions from the player – with a 2D non-platforming game, the exploration is naturally simplistic. So again, I had an idea of the game I wanted to make and also a prototype that desperately wanted to be a different game.

I’d love to revisit these prototypes once I’ve finished Dead Static Drive. Now that I know what kinds of games they are, they’ll be able to be given the treatment they deserve.

What is Dead Static Drive? What’s it about? Road trips and the apocalypse, sure, but what can players expect from the gameplay?

The world is ending, but most people don’t know that. When you begin playing the game, you don’t know that. So what if it was? You’ve got your own problems.

You haven’t had a good year, but you’re trying to turn things around. Each time you play, you’re given a random character, so there will be slight differences, but their personality and setup is consistent. You’ve lost touch with a parent (your mom if you play as a woman; your dad if you play as a man). It’s at least half your fault. Last thing you heard, (s)he’d moved back to your home town, Brightwater. You’re heading back. If you can’t fix anything else, you can fix this. If only you had a little more money for gas.

Mechanically, Dead Static Drive is an investigation and exploration game. You’re given a main task, which is to find your parent, who could be dead for all you know. That’s the lead-in to the main game, which is exploration of the world and its mysteries. Just achieving that first task is a fine goal to accomplish, but it’s only the introduction to the mechanics of driving, dealing with the road, dealing with people and creating a story through investigation and responding to what you uncover. With effort, you’ll be able to push back at fate. Or you may wish to make it come sooner.

It’s a game that’s designed to be replayed with different decisions made based on what you want to achieve and what you think is important to the story according to what you think is really happening.

Dead Static Drive has a distinctly American look to my eye, but you are Australian – how’d you go about that? And, for that matter, why set it in the States rather than Australia?

Lots of references of America! And we also tend to swim in American media here in Australia, so it’s not uncommon to us. We actually have laws saying how much local, Australian-made content must be shown on TV because it’s otherwise so easy to lose all our cultural identity. Apart from football and cricket, which will never, ever die.

I’m glad you asked why it’s set in the USA because until now I’d never broken that down. I’d love to make an Australian game, but as soon as I decided that this game was set in the real-ish world I knew it was America. I think there are fundamental differences between the kinds of regional or small county areas you see in Australia and the USA – and the two would make for different games.

In the USA, there are towns that are built up and thrive for a while, and then people leave and it’s now desolate or even abandoned. Those kinds of places have a natural horror and sadness that we don’t see much here in Australia.

To a certain degree, I’m also mindful that if it was set in Australia, it would be an “Australian game.” I wanted to have the shortcut associations that you get when you pick a theme, but I didn’t want to have players get caught up in learning the differences between Australia and their own country – choosing something universally understood and a little more “default” lets me focus the player on what makes my world interesting and different.

Plus, I’m a bit of a muscle-car-loving, Tiki-culture-adoring, Americana fan boy. You guys have the best hamburgers. Actually, forget all the above philosophizing – it’s about the hamburgers.

Thoughts on Kentucky Route Zero? I feel like there is a little bit of that in your aesthetic, and there seems to be a good parallel in the approach to road trips.

Gorgeous and wonderful. I’ve only played the first chapter and I loved the whole thing. I bought the whole set based solely on the Equus Oils gas station and when I played the game I was surprised by how much it played like a modern version of The Willowdale Handcar, one of my favorite Edward Gorey stories.

I love the idea of evocative mysteries with elements that are difficult to decipher, but that can still be made sense of. I think that works perfectly with road trips, since in a road trip every turnoff not taken is an evocative mystery. You can turn your head down any side street and wonder, “What’s it like there? What happens there? Who thinks that this is home? What would I be like if I was there?” There’s something romantic and a little sad at how often these questions go unanswered in our daily lives.

When I started Dead Static Drive I know I was informed by their art style because I’d played it already, but I hadn’t thought about the game in a while. I maintain a heavy Pinterest board for my references and when browsing for pins I stumbled back onto a Kentucky Route Zero Equus Oils image – all the memories of that game came flooding back. I was surprised that I’d had a blind spot for how obviously inspired by their game I was, but I hope that there’s plenty enough differentiating the two that it comes off as a homage at most.

What’s the town of Crow’s Demise like? I find it interesting that the short video and that evocative name manages to conjure up a dreamlike (or nightmare like, I suppose) America, the same kind of landscape as Twin Peaks or Silent Hill. What other places will we visit along the way?

Thank you! I love the power of words to be evocative, so I want to make sure I choose titles and flavor text and dialogue that help reinforce the feel of locations and the general vibe.

Crow’s Demise is an old farming area where crops are bad. The town area still has a few people living there, but it looks like they’ve mostly moved on. The Crow family that the town is named for are among the missing. There are lots of crows, and the people who are left seem to be missing something, too. You can see shadows moving in the rows of corn.

Through exploration of the area you can learn about what is causing the crops to fail. There’s an old cairn that softly hums as you approach it. Untended scarecrows have been left to decay in favor of pesticides for controlling spoilage.

But that’s just the natural world. As your sanity wanes, you’ll become attuned to other features of each location.

I have 21 locations planned now, but the number is not set in stone yet. There’s Brightwater, which isn’t as nice as it sounds. Shaded Woods is a cool drive through the treetops along a modern bridge built to bypass an older, crumbling bridge, which was in turn built to replace a rotted, fungal bridge. The Path to the Mount is a lonely trip to an apparent dead-end.

Can you talk about the design of the Coven People a little bit? I find them extremely intriguing – I especially like the fact that you can see the spinal column from all angles. Did anything in particular inspire them? Despite your flair for Americana, the black silhouettes with white details seems to hint at indigenous Australian art.

That’s a great catch about indigenous art. I could be channeling some of that. I grew up with a book called The Quinkins, which features two types of Aboriginal dreamtime creatures – one that was friendly, but one that ate children. I remember thinking it was pretty terrifying when I was young, especially since the creatures were drawn as distorted people and spoken about as if they existed.

That’s a great catch about indigenous art. I could be channeling some of that. I grew up with a book called The Quinkins, which features two types of Aboriginal dreamtime creatures – one that was friendly, but one that ate children. I remember thinking it was pretty terrifying when I was young, especially since the creatures were drawn as distorted people and spoken about as if they existed.

I remember the creatures could hide in cracks and shadows and they just felt so unnatural to me.

Because I want to include nature worship in the game, I want to be thoughtful of what kinds of artwork I use because I’d hate to be appropriating somebody’s culture in a way that was disrespectful of the people or relied on stereotypes (or even that made real beliefs look like hocus-pocus). And since Americana isn’t my culture, I’m also aware that’s a risk I face with the entire game.

The design of the coven people stems from a conversation I had with a workmate a while back. We were talking about achieving an effect like the one in Street Fighter 2 when your characters are hit by Blanka’s electricity and you can see their skeleton, like an x-ray.

There’s a common videogame effect for toon shading where you take a 3D model and turn it inside out, then “fatten” up all the limbs, and you draw this in addition to the regular model. Because 3D models are often drawn with backface culling (transparency when viewed from behind) you can only see the parts of this fatter mesh that are behind your original model. I always wanted to do that for an x-ray character, and with the need for nature worshippers I thought this would be the perfect fit.

There’s a common videogame effect for toon shading where you take a 3D model and turn it inside out, then “fatten” up all the limbs, and you draw this in addition to the regular model. Because 3D models are often drawn with backface culling (transparency when viewed from behind) you can only see the parts of this fatter mesh that are behind your original model. I always wanted to do that for an x-ray character, and with the need for nature worshippers I thought this would be the perfect fit.

I’ve just looked up images of Street Fighter IV and it looks like they did this effect in the exact way I’m describing. So boo to me, I thought I was being so original!

One of the things that struck me about the game is that it doesn’t look like an Unreal Engine game – I think UE3 games like Arkham City gave folks a lot of preconceived notions about what a UDK game looks like. How much of UE4 are you working with, how much have you pulled out to the junk pile, and what is the process like for modifying it?

The best thing about Unreal is the editor. There’s a reason Unreal was used for so many games in the previous gen. I don’t think it’s ever been successful at being the prettiest game engine but it’s so successful at making large-scale games.

The old Unreal (UDK/UE3) had a lot of sophisticated features – the material editor, the Cascade particle system editor, Kismet visual scripting and Matinee for cutscenes – all of which meant you could get games working with very little need for external tools. UE4 has those plus Blueprints, a far better UI and full source-code access for everyone. Interestingly, Blueprints alone work like the old Kismet visual scripting but so insanely beefed-up that even as a C++ programmer with years of experience I’m finding it hard to have reasons to code in C++ anymore. But check on me again when I need to optimize the game!

Mostly all of my Dead Static Drive build is 100% OG Unreal. I’ve added some new features to the engine – new lighting models for different comic-book effects and some tools to debug the visuals so I can tweak them even more – but the largest changes to the base engine are the shader overhauls.

I’m using a deferred shading system, and that means that the engine paints your game to a bunch of different canvases, with each canvas containing different information on what is in your scene. One canvas has the color of an object; another has how metallic the object is, and another has the surface direction so you can calculate lighting. After all these canvases are painted, Unreal has a few consistent ways of blending all this information together for the final effect.

I needed to add new canvas types, but also I made big sweeping changes to some of the ways these canvases get blended together.

Of course, you’ve won an Unreal Dev Grant. How’d that work? What kind of impact has it had on the project?

I wanted to demo Dead Static Drive at GDC and I found out that Epic was offering eight Unreal developers a booth space to demo their games. As soon as I heard about these spaces, I knew I wanted to be one of them.

I put together a build that showed off the key elements of the game – the theme and some of the basic mechanics – and then made a video. I sent the video and a short description over and waited. Eventually I heard I wasn’t one of the lucky few; I was elated that I hadn’t been flatly rejected.

I went to GDC anyway, on my own dime. I had a great time meeting people from all over the world and had an awful time trying to pick which sessions to attend. I visited the Epic pavilion and had a look at the games that were on display – one game was Space Dust Racers, which is made by some guys I used to work with back at Transmission Games. I was glad they got a showing.

During one session on Wednesday, I checked Twitter on my phone and my feed had exploded. And by “exploded,” I mean that I had about ten new followers and a couple of dozen mentions. For me, getting one retweet is kind of a big deal, so I had no idea what was happening.

When the Twitter app finally caught up, I saw that I’d been mentioned as an Unreal Dev Grant winner in a few articles. And I’d been granted $15K USD (which is nearly $20K in Aussie dollars – that buys a lot of kangaroos). I tapped onto the first article mentioning me and scrolled down to the bit congratulating “Mike Buttsney.”

They’d read my screen name in Twitter, which I’d set to Buttsney as a joke. The next article: same thing. I got in touch with the first two, but by then it’d taken on a life of its own and the internet now knew me as Mike Buttsney.

A bunch of sites still have me listed as Mike Buttsney but I sort of don’t want them to fix it. When I got back to Melbourne my mates at work welcomed me back with a “Mike Buttsney” nameplate.

This is a hard call, because $15K is extremely helpful, but what I appreciate most about the grant is that Epic are supporting and encouraging me – Dead Static Drive is, I think, an inherently niche game, and having support to find an audience will help me in ways that are hard to buy. As a niche game developer, I want the audience to know the game exists and to be able to find it and play it.

Hypothetical question: you’ve finished Dead Static Drive and now money is no object. You’ve kicked Notch out of his fancy house, you can hire as much staff as you want, you have unlimited time and resources – what is the next game you make?

Poor Notch! This is a brilliant question. I’ve got so many ideas, but then who doesn’t?

I’m still not convinced about how broadly adopted VR will ever be, but with more time and resources I’d love to make a VR heist getaway driver game. I love the idea of having to circle blocks, looking over your shoulder, and then drive like crazy to get away. I’m picturing something floating between Bullitt and Drive for chases and overall vibe. I’d also love taking a horror edge to it in some way…I’m swimming in horror driving ideas at the moment!

Regardless of the game, I’d get Kurt Russell to do voice acting and we’d chat over coffee one day and maybe become friends.

———

To see more of Dead Static Drive, check out Mike’s Polycount page. To see the game in action, check out this video of an early build.

Stu Horvath is the editor in chief of Unwinnable. He reads a lot, drinks whiskey and spends his free time calling up demons. Sometimes, he plays with toys and calls it “photography.” Follow him on Twitter @StuHorvath.