Avengers Assembled!

In a rare turn of events, we’re publishing a story from Unwinnable Weekly on the internet early! This will appear Unwinnable Weekly Issue Forty-Two. Purchase a one-month subscription to make sure you never miss an issue!

———

The Avengers rule popular culture. With the impending release of the second Avengers film, and Marvel’s massive Secret Wars crossover promising the reshape that entire comic universe, the flagship superhero team is at the height of its cultural power (at least, until the next films). But these stories are built on decades of work for the team and its characters — and especially the work done on The Avengers in the decade before the Marvel Cinematic Universe. During this period, a sequence of massive crossover events (House of M! World War Hulk! Secret Invasion!) kept Marvel comics in the pop culture discussion — and once their films got popular, became a major source of story inspiration.

The heart of the 2000s era of Avengers comics is 2006’s massive “Civil War” event. And Civil War is big again. Reports say that the third Captain America film will be subtitled Civil War and will co-star Robert Downey Jr.’s Tony Stark, and there’s another Civil War comic series on the way. And it deserves to be big — it’s the most important event of modern Marvel comics, which have became the source for one of the dominant cultural juggernauts of today — and Civil War, and the other comics of its era, certainly speak to that era.

Since the mid-2000s, Marvel comics have relied on massive crossover events. Civil War was the most important of these thematically and all its old criticisms, plus some new ones, are back in the discourse. The core problem: [hi]the main series[foot]Marvel’s Avengers-based crossovers tend to use a structure that has one main series, a couple supplemental and temporary series alongside like Civil War: Frontline, and events spilling over into ongoing comics like The Amazing Spider-Man, New Avengers, etc.[/foot][/hi] is an incoherent mess, a supposed ideological battle between Captain America opposing superhero registration with the United States government, and Iron Man supporting it. The former’s anti-establishment ideals are half-baked, and the latter’s ruthless pragmatism is never portrayed as anything other than proto-fascism. Over at Slate, Jamelle Bouie argues that Civil War is right-wing propaganda, which I feel might be overstating its intellectual coherence.

But Civil War is not merely the seven issues of the event itself. Its writer, [hi]Mark Millar[foot]Millar’s most famous work occurs in the Ultimate universe, a total Marvel reboot in the 2000s that, for several years, seemed more vibrant than even the main universe and is another major influence on the Marvel Cinematic Universe. But that’s a story for another essay.[/foot][/hi], is well-known for throwing a bunch of superficial ideology into a story as an excuse for fighting. It can work — his stories often have a powerful violent momentum to them — but he was absolutely the wrong choice for the tragic thematic centerpiece of nearly a decade of Marvel storytelling.

The point of Civil War wasn’t just to have a cool punch-fight between Iron Man and Captain America. It stood as part of a greater whole, where between 2004 and 2009, with a prologue and finale extending a bit before and after, Civil War was the centerpiece Marvel’s attempts to force all of its Avengers-related heroes outside of their normal boundaries.

Your basic superhero tends to default to nice comfortable life. He has the power to do dangerous things, but society and the government tend to provide him with the support to not worry about the aftermath of his punch-ups. He’s either inherited wealth, is a genius inventor/businessman or friends with one, or has a power that makes needing money irrelevant. It’s a comfort zone for writers and publishers, too, they can give their heroes all the adventures they want without worrying about the messy consequences. The Avengers tended to fall into this category, as did most of their individual members.

That renders that basic hero rather dull at times. It’s worth noting that three of Marvel’s biggest successes — Hulk, Spider-Man and the X-Men — all diverge from this model, particularly in that all of them have the government and society working against them.

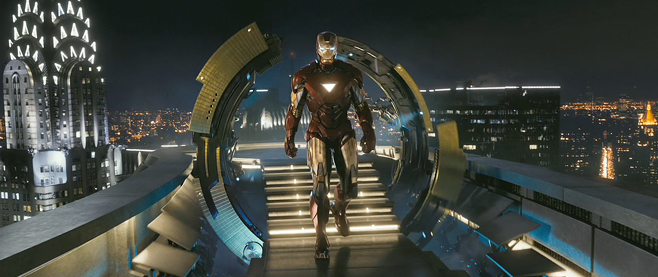

I also used the pronoun “he” intentionally: most of the heroes are men and not just men, but men who embody patriarchal ideals. Tony Stark, Iron Man, is a supergenius and the CEO of a major corporation who also puts on a suit and saves the world. Reed Richards of the Fantastic Four is even smarter, able to invent essentially anything while running the Fantastic Four as a marketing empire. Captain America, he’s the ideal of American masculinity, always making the right choice for the right reasons, even when it’s impossible. And Thor, well, Thor’s pretty much the fucking Norse God of Virile Masculinity.

So in the mid-2000s, Marvel took this model and said “let’s see what happens when we burn it down!” Various writers had subverted this comfortable masculine heroism before, with stories like Tony Stark’s alcoholism or Thor being humbled in the form of the weakened human Donald Blake. But this era of the Avengers systemically worked to push almost every hero out of their comfort zone across the entire Marvel Universe, using a series of company-wide crossovers. It did this by sending many of the heroes underground or on the run, removing their governmental sanction, while a few others ended up being promoted into positions of power and responsibility (Tony Stark runs the world for a couple years). In doing so, it turns into a first implicit, later explicit, examination of power and patriarchy using men in a spandex punching each other.

These are the comics that defined the Civil War era — and are also some of the best:

Daredevil vol 3 (1998): 16-19, 38-40, 76-81

The author of the bulk of Avengers stories in this era was Brian Michael Bendis, who had become famous earlier in the decade for his work on Ultimate Spider-Man and Daredevil. In the former, he demonstrated the ability to reboot a franchise; in the latter, he took an established hero and moved him out of his comfort zone. Daredevil’s (a Batman-like superhero more focused local street crime, as opposed to a world-saver) secret identity is Matt Murdock, a high-class lawyer in New York City. With almost his first move, Bendis outed Murdock as Daredevil, which threatened his life, his friends’ lives and his legal career. The latter was new to Daredevil — the legality of any case involving Murdock came into question, threatening the release of any villain he’d ever put behind bars. Daredevil was not allowed any comfort zone; there was no retreat back to normality after solving the latest crisis.

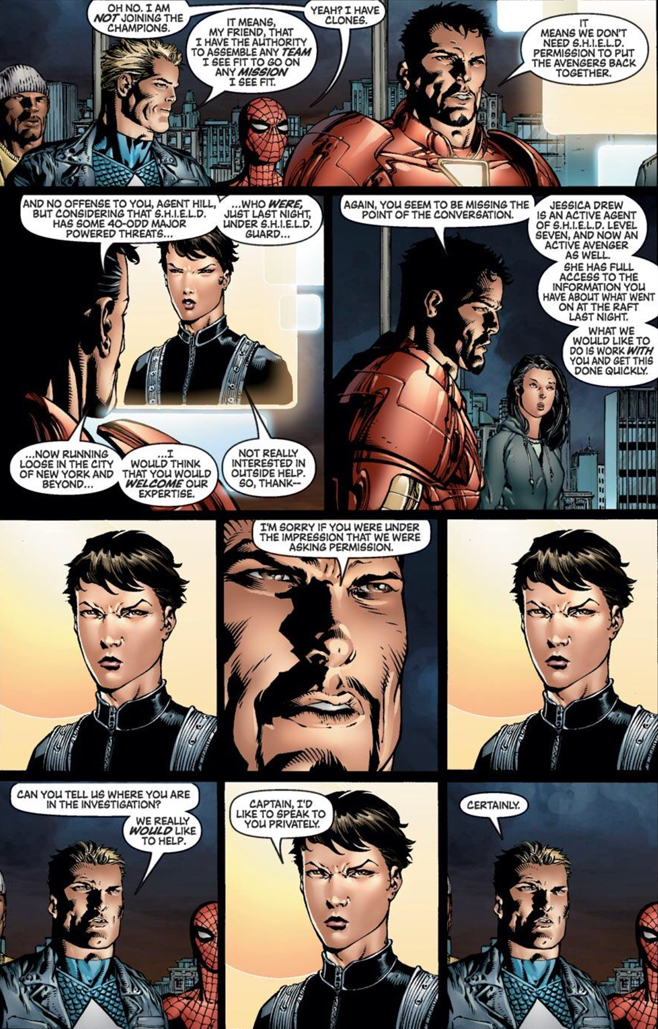

Secret War (2004)

New Avengers (2004): 1-25

Bendis set out to treat the Avengers similarly. In three crossovers from 2003-05, he rebooted the team and pushed them out of their comfort zone. First, in Secret War, he used post 9/11-Iraq War paranoia to push Nick Fury, the closest thing Marvel’s superheroes have to a patriarchal boss, from his role as Director of S.H.I.E.L.D. (Fury’s successor [hi]Maria Hill[foot] [/foot][/hi] took a much more antagonistic role in dealing with superheroes). The next year in “Avengers Disassembled” Bendis does exactly what the title proclaims, clearing out a lot of the old heroes and making a new team. His New Avengers included traditional patriarchal heroes like Captain America and Iron Man, but he also added two of Marvel’s most popular rebels, Spider-Man and Wolverine, as well as Luke Cage (a black, Harlem-based hero) and Jessica Drew, the recently under-utilized Spider-Woman.

[/foot][/hi] took a much more antagonistic role in dealing with superheroes). The next year in “Avengers Disassembled” Bendis does exactly what the title proclaims, clearing out a lot of the old heroes and making a new team. His New Avengers included traditional patriarchal heroes like Captain America and Iron Man, but he also added two of Marvel’s most popular rebels, Spider-Man and Wolverine, as well as Luke Cage (a black, Harlem-based hero) and Jessica Drew, the recently under-utilized Spider-Woman.

The events of the 2005 crossover event, an alternate universe called House of M, had more ramifications on the X-Men’s side of the Marvel universe, but it drove more of a wedge between the superheroes who knew what happened and the government that didn’t.

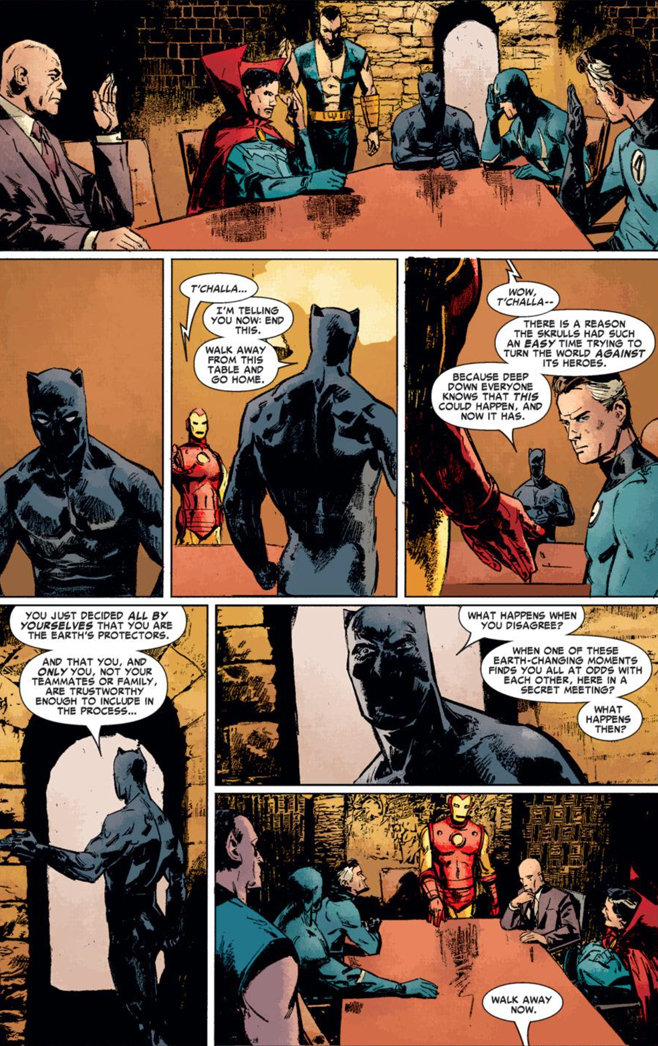

New Avengers: Illuminati (2006):

Bendis’ biggest move toward shattering the ideal of the patriarchal superhero was the creation of the Illuminati, a council of the smartest and most powerful heroes in the Marvel universe, intended to guide it toward peace and stability. The six members included: Professor Charles Xavier, founder of the X-Men and the most powerful telepath on Earth; Tony Stark, genius scientist, CEO and Iron Man; Reed Richards, supergenius and member of the Fantastic Four; Dr. Strange, former genius surgeon and current genius wizard, Sorcerer Supreme of the Marvel universe; Black Bolt, king of the Inhumans, an isolationist kingdom of genetically enhanced superhumans; and Namor, the king of Atlantis.

The Illuminati may be the best collection of 1960s ideals of superheroes and leaders. Stark and Richards are technocrats who use science for progress without politics. Professor X is the great liberal of the Marvel universe, espousing peaceful coexistence for humans and mutants. Strange represents the merging of the rational and the magical, a man of medicine who found and appropriated “Eastern” wisdom. Black Bolt is the wise leader, who guides his people without even speaking. And Namor…well, Namor’s a loose cannon and not really an ideal, but he is one of the very oldest of all the Marvels, and connects the group with the shared history of the setting.

Thus the Illuminati are all older, all white, all male. They are the embodiment of patriarchy, both literally as older, powerful, men, and in terms of being the ideals. If wise, strong, good men like these were running the world, the idea goes, then the world would be a better place.

But the Illuminati are also dismal failures, and that’s where the fun starts. It’s no coincidence that the African, anti-imperialist Black Panther is the first to criticize the group and refuse membership, due to its paternalism. And he was right to do so.

he next three major storylines after the full introduction of the Illuminati are all disasters in the Marvel universe, and all instigated by the group. First, the Illuminati are shown making the decision to fire Bruce Banner, the Hulk, into space, as they decided he’d become too much of a problem for Earth to deal with. To nobody except the patriarchs’ surprise, Hulk comes back and sacks New York City in 2007’s “World War Hulk” crossover. Then, in the Illuminati’s series, the group is shown discussing and taking action during or after some of the Marvel Universe’s biggest events. So, after the famous Avengers “Kree/Skrull War” arc, the Illuminati leave Earth to posture against the Skrull Empire, comprised of a race of shapeshifting aliens, a bit of hubris that leads to 2008’s big event, the Skrull Secret Invasion. (Which destroys New York City again — Marvel had a bit of a 9/11 issue.)

Civil War (2006):

Amazing Spider-Man: 529-538

Fantastic Four: 538-543

Mark Millar’s main story, of the Avengers being torn apart by a Superhero Registration Act, doesn’t hold up to even the slightest scrutiny at a philosophical or political level, but as far as Captain America-punching-Iron Man stories go, it does have enough momentum to be readable. And even Millar’s rampaging id of a comic possesses certain inadvertent insights. The emotional climax of the series comes when Thor — long-since disappeared — appears to break up a fight, apparently on the side of the pro-Registration group. This Thor, however, is a clone made by Tony Stark and Reed Richards — and the clone goes haywire; its unbending morality almost immediately killing Bill Foster, the former Avenger known as Black Goliath.

It’s almost too perfect: Marvel’s two greatest technocrats, two members of the Illuminati, team up to recreate the perfect blond-haired blue-eyed man. They apparently succeed, he serves their will, policing an uprising from the weak…but he totally lacks empathy and kills the first black man who appears to defy him. It seems very unlikely that Marvel and Millar were making a deliberate critique of American paternalism — but it’s there anyway.

Bill Foster’s death at the hands of a rampaging, pro-Registration science experiment gone wrong illustrates another major issue with Civil War — Iron Man’s side never seems anywhere near a viable proposition. Steve Rogers’ philosophy is incoherent, but Tony Stark’s is just a [hi]half-step away from fascism[foot] [/foot][/hi], up to and including a secret Guantanamo-like prison in a dangerous parallel dimension. What’s worse is that Marvel never seemed to notice — “Whose Side Are You On?” advertising always presented both sides as equally valid.

[/foot][/hi], up to and including a secret Guantanamo-like prison in a dangerous parallel dimension. What’s worse is that Marvel never seemed to notice — “Whose Side Are You On?” advertising always presented both sides as equally valid.

As messy as Civil War was, it wasn’t necessarily a bad idea. The side stories involved make it clear that Marvel had the right idea — they just messed up the execution.

The best of the lot is Spider-Man, where once-Babylon 5 scribe J. Michael Straczynski is handed what might be the greatest possible comics story for him, with good people on different sides of a violent philosophical debate and the fundamentally decent Peter Parker trapped in the middle. There the implications of the conflict on the characters, both conceptually and in terms of physical danger, are made apparent.

On the team side, the Fantastic Four stories — the first half written by JMS as well, with a second half by Dwayne McDuffie — focus on the [hi]disintegration of a team[foot] [/foot][/hi], with Reed Richards’ patriarchal certainty and willingness to put the ends ahead of the means splintering him from his teammates. Meanwhile, Bendis, in his New Avengers, comes at the same ideas from different angles, with quiet vignettes of why and how each team member ended up on the side they did.

[/foot][/hi], with Reed Richards’ patriarchal certainty and willingness to put the ends ahead of the means splintering him from his teammates. Meanwhile, Bendis, in his New Avengers, comes at the same ideas from different angles, with quiet vignettes of why and how each team member ended up on the side they did.

Finally, the Civil War: Front Line title is often praised. It’s primarily the story of a pair of reporters attempting to cover the conflict, and in terms of watching how regular people interact with massive superhero events, it’s fascinating. But it makes clear another of Marvel’s mistakes: treating Civil War with excessive solemnity. Marvel acted like this was equivalent to a superhero world war in Front Line and elsewhere, but the text — which only involved a couple brawls, some shouting, and a handful of minor character deaths — suggested it was a “Phoney War” that never escalated. Nevertheless, with the victory of the pro-Registration forces, Civil War did set up a fascinating new direction for the Marvel universe, which allowed half a decade of fascinating, differently-directed storytelling before being reset.

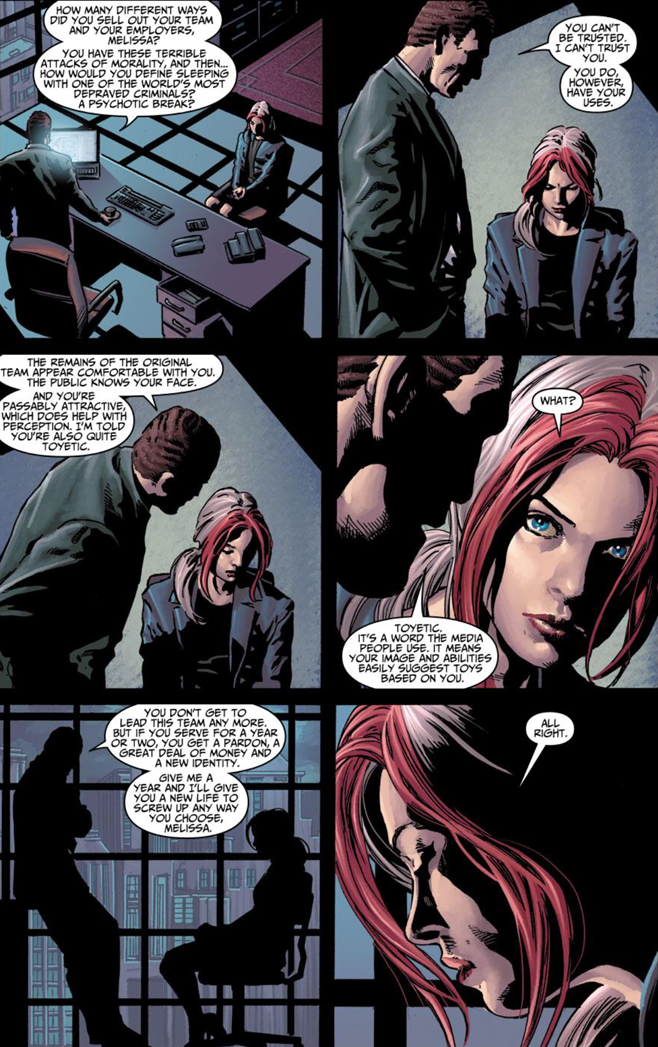

Thunderbolts (2003): 110-125

Warren Ellis’ Thunderbolts are the heart of the Civil War era, bridging both the inconsistently applied deconstruction of the first half, with the direct, occasionally vicious self-examination and satire of the latter part of the decade. Marvel struck gold with this combo. Ellis, like Millar — with whom he’s often mentioned as part of the “British Invasion” of mainstream comics — has a gift for telling stories with a violently propulsive momentum, able to veer between comedy, horror, action and more. But Ellis can maintain a consistent, audacious feel, largely because his satire feels targeted instead of slapdash. His Thunderbolts are an ideal example of the form.

The Thunderbolts are one of 1990s Marvel’s great inventions: a group of supervillains pretending to be heroes who then become an institution built on the idea of actual heroism and redemption. After the Civil War, the Thunderbolts became the government arm of chasing down costumed vigilantes. In other words, where the Bendis era of the Avengers worked to delegitimize the heroes, Ellis’ Thunderbolts was all about legitimizing the villains.

Ellis’ masterstroke is putting Norman Osborn, the Green Goblin, Spider-Man’s greatest antagonist, in charge of the Thunderbolts project. Osborn becomes the perfect villain for the Bush era — he’s a CEO who’s as concerned with marketing as he is with mass murder. Ellis just keeps twisting the satirical knife — the Thunderbolts, now with unreformed, unrepentant mass-murdering villains like Venom and Bullseye, get toy commercials in the issues.

Thunderbolts takes a deliriously toxic mix of heroes and villains, legitimacy and cynicism and all the philosophical rationalizations of the Civil War, shakes them til they explode, and dances on the shards. Ellis only writes for 12 issues, but the next handful — written by Christos Gage, covering the Thunderbolts’ role in the Secret Invasion crossover — are a fine capstone. They also set the Thunderbolts up as the new standard in the Civil War universe…..

Secret Invasion:

On its own, Secret Invasion isn’t terribly interesting — a group of aliens invade, the heroes fight back and drive them off. It’s still quite readable, with the straightforward beat-’em-up proving a refreshing change-of-pace from the somewhat muddled morality of the Civil War era. Secret Invasion’s primary importance is that Tony Stark, who’d become the leader of S.H.I.E.L.D. after Civil War, is turned into the scapegoat for the initial successes of the invasion. The apparatus of registered superheroes which he’d developed is taken over by the man who was the hero of the invasion: the Thunderbolts’ Norman Osborn.

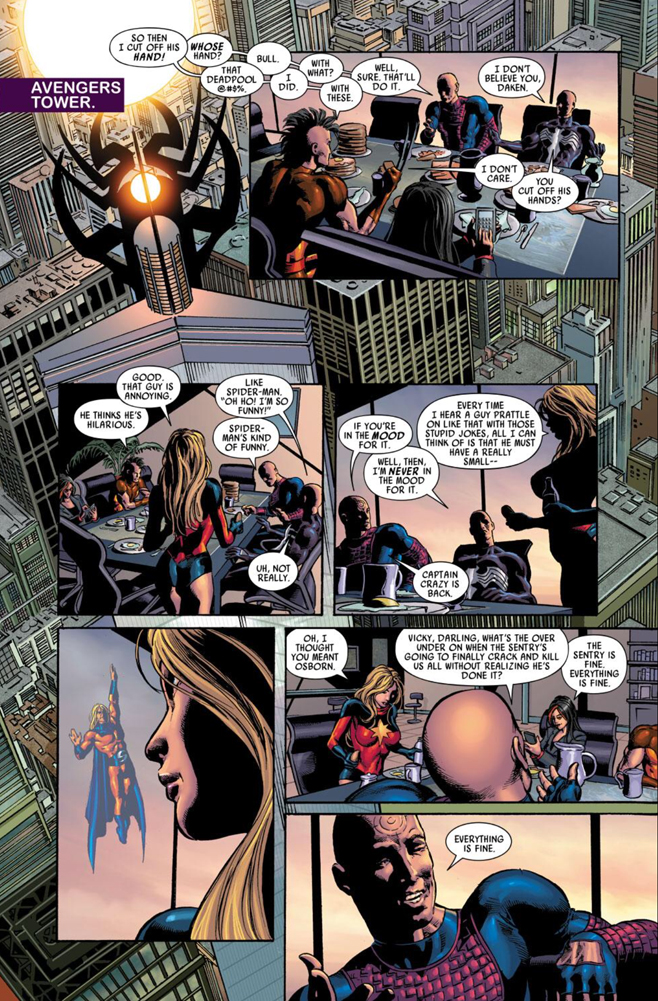

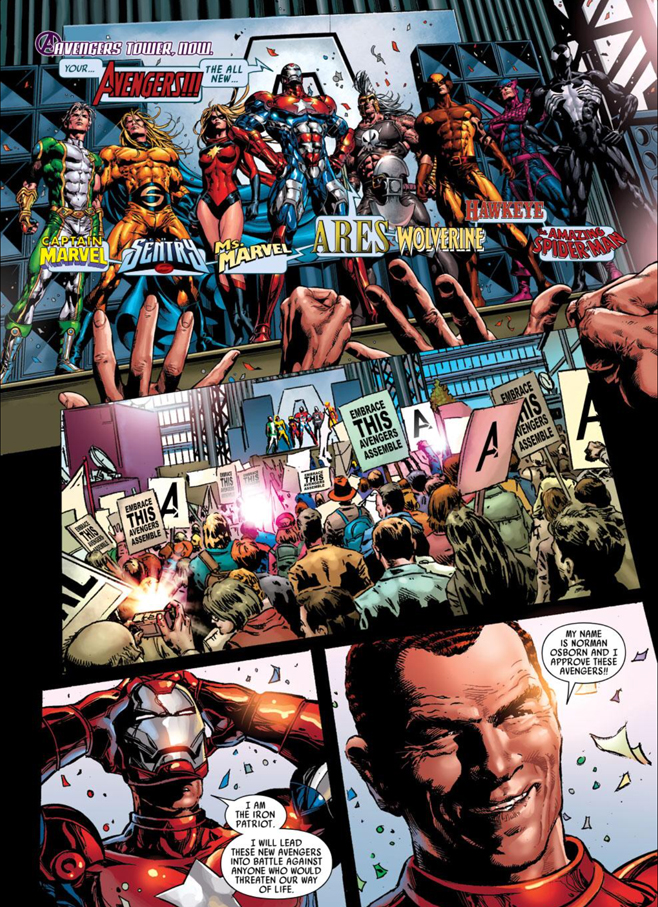

Dark Avengers (2009):

Osborn’s assumption of power in the Marvel Universe is called Dark Reign, and is treated like a crossover event, but that’s not entirely accurate. It’s more that, for a year and a half, almost every single Marvel title dealt with a status quo where the villains had power and legitimacy, while heroes had to either toe the line or work underground. It’s as fascinating and fruitful as it sounds.

The center of Dark Reign is Brian Michael Bendis’ Dark Avengers. Bendis takes Osborn, half of Ellis’ Thunderbolts and the least stable members of the prior Avengers lineup, and makes them, publicly, the new heroes…while privately they [hi]connive and backstab one another[foot] [/foot][/hi]. The new focus seems to rejuvenate Bendis, whose work on New/Mighty Avengers in the prior few years was showing some strain.

[/foot][/hi]. The new focus seems to rejuvenate Bendis, whose work on New/Mighty Avengers in the prior few years was showing some strain.

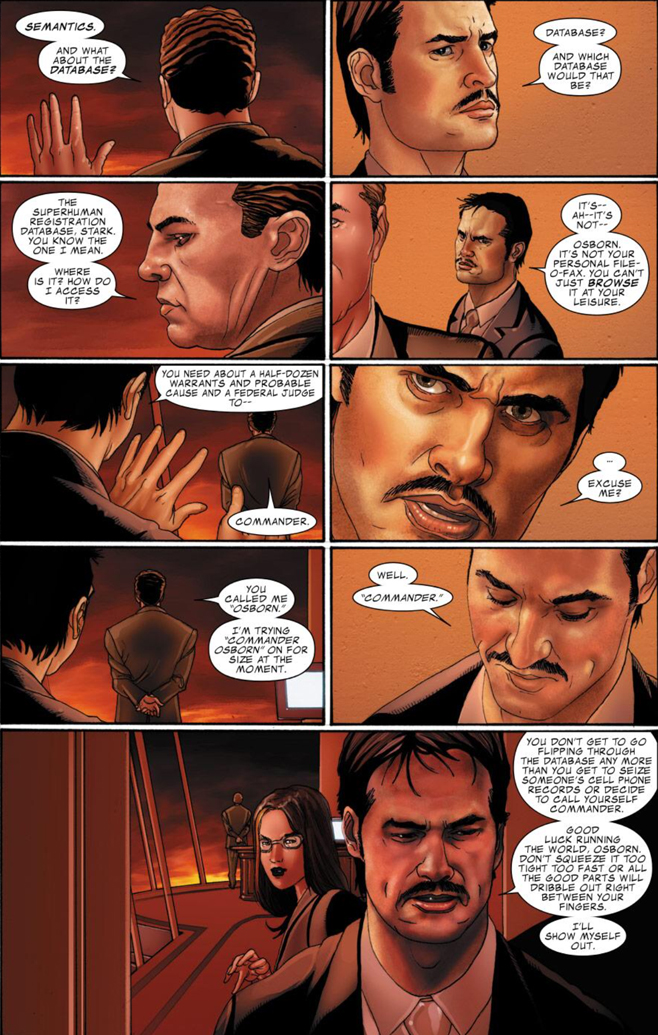

One of the best parts about Dark Avengers and Dark Reign as a whole is that Norman Osborn doesn’t breaks out of his role (with the exception of The Amazing Spider-Man series) as the Director of H.A.M.M.E.R., his S.H.I.E.L.D. replacement. His villainy comes not from some cynical Green Goblin plot, but from his desire for control, use of ends-before-the-means philosophy, and consistent choice to use sociopaths to do his will. He is Dick Cheney or Donald Rumsfeld going all out to impose his will on the world, and seeing everyone else realize what a failure it is and turning on him. In a sense, Osborn is to Tony Stark what the Thor clone from Civil War was to the real Thor — an empathy-free embodiment of the same ideals that theoretically made them heroes.

Bendis reinforces this point with the creation of the fascinating Victoria Hand character, a former S.H.I.E.L.D. employee who wanted to take a harder line than Nick Fury in enforcing global peace. She becomes Osborn’s attache, not as a cynical villain, but as a pragmatist who actually believes she’s doing the right thing. This counterbalance to the soap opera villainy of the Dark Avengers (and Osborn’s eventual collapse) works remarkably well.

Dark Reign also saw the creation of Norman Osborn’s version of the Illuminati, the “Cabal” of villains or ex-villains featuring him, Loki, Emma Frost, Dr. Doom, The Hood (leader of a criminal supervillain mob), and Namor once again. But while Bendis had fun with the form and the reversal of roles and expectations, a pair of newer writers would use it to explicitly critique the patriarchal heroes who made so many mistakes in the Civil War era.

Invincible Iron Man (2008) #8-19:

Bendis and Millar may not have been explicit about what they were trying to do in breaking down and re-examining the patriarchal heroes of Marvel’s history, but part of the story of the era is that the next generation of Marvel writers did. Chief among them: Matt Fraction.

Fraction got his first shot at a major hero in this series, and he took full advantage of the opportunity, “disassembling” Tony Stark during and after the Secret Invasion. It’s fertile ground for deconstruction: Tony gambled everything on his ability to protect the world, and didn’t just fail during the Skrull Invasion, he failed in such a way that his former business rival took over his role and his armor. Norman Osborn became the Iron Patriot, while Stark was the target of an international manhunt.

Everything that Tony Stark stood for — the brilliant CEO, the innovative scientist, the supremely competent hero, and the charming playboy — is removed, piece-by-piece, examined, and discarded. Stark loses his mind, his technology, and his company. Instead of being the rational patriarch, he gets by almost entirely on an animal cunning — and his relationship with three women: Pepper Potts, Maria Hill, and the Black Widow. Civil War-era Iron Man was defined by his win-at-all-costs style and refusal to show weakness, but it’s his weakness that ends up granting him survival in the end.

Fraction’s Iron Man isn’t just an intellectual achievement, though. The twelve Dark Reign issues are among the most propulsive of any comics I’ve read. The Dark Reign storyline’s end in issue #19 comes with a twist that heralds Tony Stark’s physical victory and ethical redemption that almost made me gasp at how well it forced Stark to confront himself. Salvadore LaRocca’s art, meanwhile, has an intensely personal focus that fits the overall theme of the man in the metal shell being forced to confront his human mistakes.

Dark Reign: Fantastic Four (2009):

Like Fraction, Jonathan Hickman is one of the biggest writing stars to emerge from this era, and like Fraction, his contribution to the Dark Reign sequence is dazzlingly audacious. Unlike Tony Stark, Reed Richards wasn’t forced to examine his role in the Civil War and subsequent disasters. But, with Norman Osborn suddenly running the world, he was motivated to do so anyway.

The mini-series is fascinating because it takes the unspoken themes of the Civil War era and makes them explicit. Bendis’ pieces largely avoided direct engagement with the themes in favor of delving into character history and continuity, while Millar waved his hands at relevance in order to give story apparent depth. But Hickman and Fraction both seemed willing and delighted to directly engage with the idea of what it meant to be a hero, what the fights for ideology meant, and the role of the super-human in a still-human world. Hickman also manages to combine that depth with a rollicking adventure story, as the other members of the Fantastic Four bounce through [hi]hilarious alternate dimensions[foot] [/foot][/hi]while the kids resist Norman Osborn’s strategies.

[/foot][/hi]while the kids resist Norman Osborn’s strategies.

It’s also the prologue to Hickman’s longer-term run on the series, so a morally ambiguous ending, with Richards potentially embracing a role as a lone philosopher-king, is an exciting development for the post-Civil War storytelling. The next group of writers had learned from the last.

Siege:

Dark Reign and the Civil War era both come to a conclusion in Siege, a rather short crossover event where Osborn and his remaining forces attack the Norse gods. It leads into the Heroic Age, Marvel’s term for, well, all the good guys being in charge and on the same side again. Instead of focusing on Osborn, though, it’s more about the conclusion of the Sentry’s story.

The Sentry is a Superman-like figure that Bendis integrated directly into Avengers mythos throughout the Civil War era. He’s a little inconsistent, though, and never quite seems to be as compelling as Marvel wants him to be. That said, Sentry’s story does fit the theme of the era — he’s the embodiment of masculine power, but those who interact with him can’t trust him to safely contain himself.

Perhaps the best thing about Siege, however, is the way it repositions one of Marvel’s chief villains, the Norse god Loki. Another new Marvel writer, Kieron Gillen, took the God of Mischief and gave him a chance at redemption. In Gillen’s hands, Loki becomes a chaotic, untrusted hero, both in Journey Into Mystery as well as Young Avengers, two of the highlights of the post-Civil War era.

Avengers Prime (2010):

After Siege, Tony Stark, Steve Rogers and Thor, the “prime” Avengers, are alive and on the same side for the first time since “Avengers Disassembled.” What better way to repair their relationship than via beating up mythological Norse creatures together? Fun and satisfying, though also a return to the heroic status quo after half a decade of chaos. It’s a worthy capstone.

———

Following the end of Siege, Marvel shifted into what it called “The Heroic Age” as a return to traditional storytelling. Its focus moved away from the corruption of power and the paternalism of its supposed greatest heroes to alternate dimensions, time travel and especially secret conspiracies. It will remain to be seen whether the return of Civil War on film and on the page will bring back the self-examination of the Civil War era of Avengers comics.

* * *

Further Reading

Fantastic Four (1998): 67-70, 500-508

Mark Waid’s run on Marvel’s first family seems like a charming romp through their universe at first, but reaches its darkest point when Dr. Doom reappears, as a magician, to attack to the family. It drives Reed a little nuts — to the point where he attempts to take over Doom’s nation, Latveria, and has to confront his team, the citizens, Latveria’s neighbors and the United States in order to combine power with leadership. It, like Bendis’ Daredevil, feels like a dry run for the Civil War era.

Captain America (2004):

While Ed Brubaker’s Captain America series does cross over with the main Avengers stories — particularly during and after Civil War — it doesn’t necessarily connect with the other themes I’ve been discussing. That’s fine, though, as it’s great to have a straightforward superhero romp running alongside the deconstructions and reconstructions of the heroic idea during the Civil War era. This is a great intro to the character, the Marvel Universe and to action comics generally, with writing and art combining to give the stories fantastic momentum.

Young Avengers (2005):

Alongside the New Avengers launch, Young Avengers brought in the idea of the rights and responsibilities of would-be superheroes. But the themes aren’t why it’s important: it introduced the world to the wonders of Kate Bishop and Cassie Lang.

X-Factor (2005):

I’m generally not discussing the X-books in this piece, but Peter David’s reboot of X-Factor as a detective agency for ignored X-Men is fun, smart, and emotionally affecting — and has a huge focus on superhero relationships with the government, even — especially — when they don’t make any sense.

She-Hulk (2005) #15-18:

The She-Hulk series that ran longest through this era changed tone and focus fairly rapidly, but for these four issues — when Jennifer Walters joins Tony Stark’s Hulk-busting outfit and attempts to work in the new, pro-registration world — may be the best example of how that registration was supposed to work. It’s also a great example of how it all falls apart as soon as Jen discovers the truth about Stark….

Ms. Marvel (2006):

The biggest non-X-Men effect of House of M was that Marvel recommitted to Carol Danvers as their premiere superheroine, after some years of disuse for the erstwhile Binary and Warbird, and future Captain Marvel. The series itself is pretty inconsistent, unfortunately. It can be great in its human moments, like Danvers’ flirtation with Spider-Man and her rivalry with her Avengers replacement, Karla Sofen during Dark Reign. But it’s also reliant on alien possession and reality-bending children, never a good sign.

Nextwave:

Ellis’ Thunderbolts series fits directly into Marvel’s Civil War era, but his other all-star 12-issue series in the mid-2000s, Nextwave, is fantastic as well. It’s more hilarious parody than vicious insightful parody, but there’s more than room for that in the oft-overserious Marvel universe.

Annihilation:

The Annihilation series showcases Marvel’s superpowered storytelling at its best concurrently with the Civil War era. It’s got similar questions of leadership and power, but because it’s set in the wider universe, allows more chance for massive change. For reading order, I suggest Thanos (2003) to Drax (2005) Annihilation to Nova to Anihilation: Conquest to Nova/Guardians of the Galaxy.

Avengers: The Initiative:

(Oddly, Marvel doesn’t have the first issue available digitally.)

Portrays the government-run young superhero training camp after Civil War. It’s an uneven but largely entertaining look at the pratfalls of superhero registration.

Secret Warriors:

Along with Fantastic Four, this is Jonathan Hickman’s other dive into Marvel’s deeper themes at the end of the Civil War era. It’s not quite as immediately successful — it’s a bit too reliant on knowledge of Marvel’s continuity — but eventually turns into a rollicking adventure.

———

Rowan Kaiser is a freelance pop culture critic. Support his Patreon. Follow him on Twitter @rowankaiser for unimportant video game tweets and very important cat pictures.