Last Week’s Comics 11/26/2014

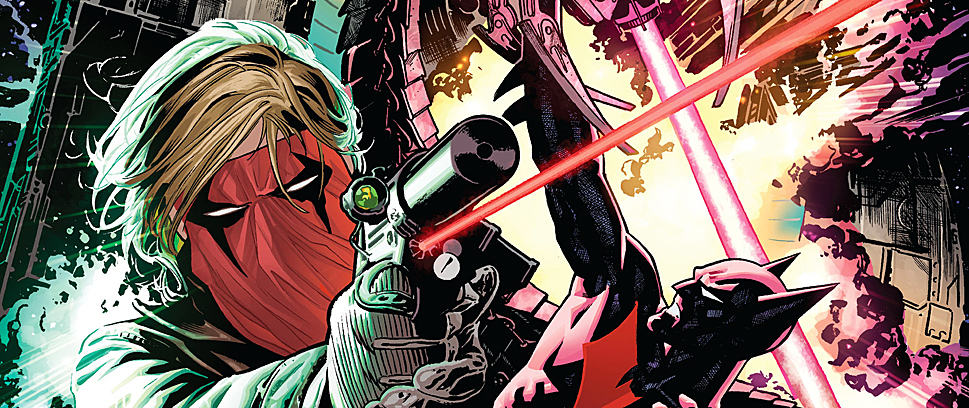

Batman ’66: The Lost Episode #1

(DC – writer: Harlan Ellison and Len Wein; artist: José Luis García-López)

One of my earliest memories is watching re-runs of the Batman 1966 TV series. I couldn’t tell you which episode I watched, but the bright sets, the colorful costumes and the sound effect cards left an impression that’s lasted a lifetime. Batman introduced me to the Batman mythos. Caesar Romero was my first Joker, Julie Newmar was my first Catwoman and Frank Gorshin was my first Riddler. As I graduated from TV to comics, I brought those impressions with me. The more I read, the more I learned about the world beyond the TV series. I learned about other classic rogues like Scarecrow, Poison Ivy and the most infamous of them all, Two-Face!

Based on a treatment by science fiction legend, Harlan Ellison, “The Two-Way Crimes of Two-Face” was meant to introduce Batman’s friend turned nemesis, Harvey Dent, into the television canon. Sadly, the episode never made it to full script and subsequently to air. Two-Face’s lost episode is the stuff of legend. I remember reading about it as a kid. I think it was a stray mention in Starlog or Comics Scene, I’m not really sure. All I knew was that there was a missed opportunity.

Based on a treatment by science fiction legend, Harlan Ellison, “The Two-Way Crimes of Two-Face” was meant to introduce Batman’s friend turned nemesis, Harvey Dent, into the television canon. Sadly, the episode never made it to full script and subsequently to air. Two-Face’s lost episode is the stuff of legend. I remember reading about it as a kid. I think it was a stray mention in Starlog or Comics Scene, I’m not really sure. All I knew was that there was a missed opportunity.

Enter Batman ’66: The Lost Episode. Len Wein adapts Ellison’s treatment as a comic script, and José Luis García-López brings the story to life. The plot begins just like the show, with a daring heist! Two-Face and his gang raid an auction to steal a near complete set of priceless antiques. Once the police, Batman and Robin appear on the scene, two St. Bernards pull a now complete set to the crime scene in a little red wagon. The scene then dovetails into the Exposition Zone as Batman fills everyone in on the tragic origin of Two-Face and his pathological need to flip a coin in order to make a decision between good and bad. The story is pretty loyal to the comics, keeping Two-Face’s gruesome acid-burned face (which could be why it was ultimately never made).

Two-Face may be the special guest villain in this story, but García-López is the star. He captures the feel of the classic TV series while still working in the style that’s made him a comic book legend. His storytelling is fluid. He’s been drawing DC Comics since 1975 and he’s gotten better. Whether he’s drawing the Northby’s Auction House, the Batcave trophy room or the pirate ship Two-Face and Batman have their final battle on, the amount of detail in every panel is staggering.

The story itself is 30 pages, and the rest of the book features García-López’s designs for Two-Face, his raw pencils for the entire issue and the book closes with Harlan Ellison’s complete treatment for “The Two-Way Crimes of Two-Face.” Batman ’66: The Lost Episode is a blend of time capsule and Imaginary Story. Heck, the process stuff alone is worth the $9.99 price tag. It’s fun comics, a vision that could have been and, most importantly, a fun Batman vs. Two-Face yarn.

———

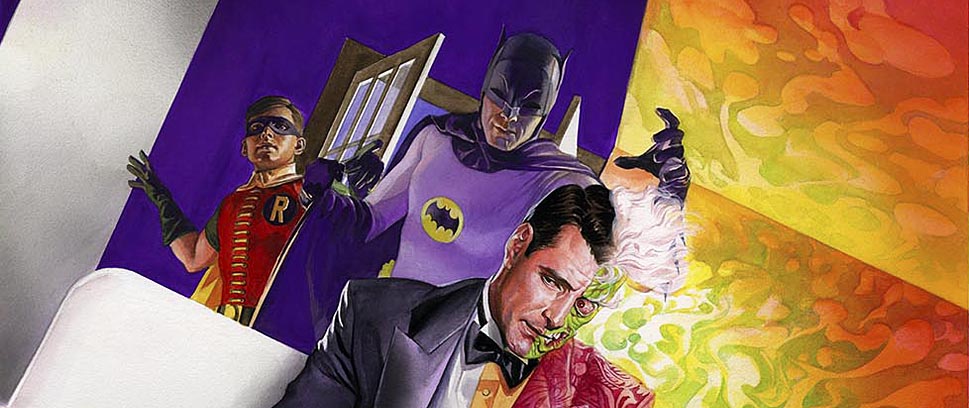

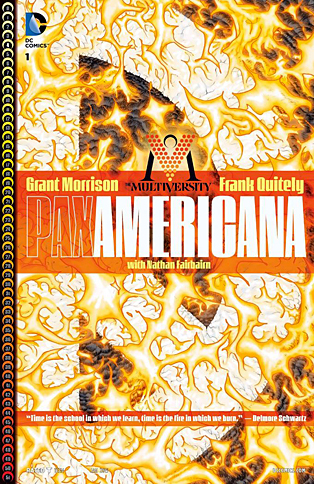

Pax Americana #1

(DC – writer: Grant Morrison; artist: Frank Quitely)

(DC – writer: Grant Morrison; artist: Frank Quitely)

Pax Americana #1 is a thing of beauty. From Frank Quitely’s cinematic panels to Grant Morrison’s heavily philosophical but utterly engaging writing, everything about this comic is perfect. A direct homage to Watchmen, Pax Americana takes Alan Moore’s original concept and offers up a story that is both linear and chaotic, weaving through its narrative seamlessly to tell a story that has occurred, is occurring, and will occur.

You need to buy this book.

Morrison’s story is, like many other Morrison stories, eclectic, enigmatic and erudite. At its core, Pax Americana is about the assassination of a beloved president and the events surrounding his death. But built into this is a decades-old mystery of America’s first superhero, a man named Yellowjacket, the history of the man who would become America’s most beloved president and the forming of the Justice League of America.

Morrison also tackles the rise and fall of the superhero. One of his characters says, “After the towers fell, we sold the dreams of children to fearful adults. The super-agents gave people something simple and strong to believe in.” The trends in movies, post 9/11, have been toward superheroes. People definitely escaped to fantasy in the face of such horror. Pax Americana is about this shift in beliefs, but done so in a way that it brings the reader in.

And this is the other impressive piece about Pax Americana. Several times, it breaks the fourth wall. One moment, in particular, has Captain Atom looking at a comic and commenting on the fluidity of the story. “The story’s linear, but I can flip through the pages in any order. Any direction. Forward in time to the conclusion. Back to the opening scene.” Here, we become Captain Atom because we, too, have such power. He continues, saying, “The characters remain unaware of my scrutiny, but their thoughts are transparent, weightless in little clouds. This is how a 2-Dimensional continuum looks to you.” He turns toward the reader, “Imagine how your 3-D world appears to me.” At this point, Atom is looking directly at the reader as he closes his dialogue. “Your back pages and your future continuities. I know your origins. The secret identities that you hide from even your loved ones.”

Mind blowing, right?

But Morrison has allowed the reader to become a character in Pax Americana and allowed us to understand our roles as readers. We, like Captain Atom, can travel through the time of the comic without any restraint. We know the secrets of the characters, yet we treat this knowledge flippantly because, after all, it’s only a comic. This is our glimpse into the brilliance of Grant Morrison. For a writer to provide such introspection for his reader only further shows the man’s talent. This in-depth analysis of the comic genre occurs throughout the book, and I hope I’m communicating the many levels that Pax Americana addresses.

To be clear, though, the real star of Pax Americana is Frank Quitely. Quitely’s brilliant composition, the symmetry of the comic, the methodical pacing, the sharpness of illustrations and the ability to translate Morrison’s time-jumping narrative into a cohesive visual experience is nothing short of amazing. No space is wasted and every panel is heavy with detail. One of the most entertaining things about the comic is that you can read it through just based on the visuals, and the story would still be coherent.

The comic also raises questions. Morrison is eerily specific in his timing. Is this a harbinger of the future of the DCU? Is he hinting at some of the big changes that will occur as DC begins its push towards Convergence? I haven’t the slightest idea. What I can tell you is that Pax Americana is brilliant. It’s the kind of comic that you reopen as soon as you close it. I’ve read it through a dozen times already, and I’ve found something new in each successive read. The story touches on so many important themes around superheroes and comics that you feel like Morrison wrote this story as a commentary on comic culture, but with a deep love for the genre. It’s so metacognitive that it makes you feel unintelligent just looking at it. But it’s also so accessible that it bridges the gap between scholarly and welcoming with aplomb.

I’m not doing this comic justice. It’s brilliant. I loved it. I’m giddy talking about it. And I want so badly for other people to experience this for themselves. My only complaint is that Pax Americana isn’t ongoing. I’d love to read a 12-part series by this talented a team.

———

Uncanny X-Men #28

(Marvel – writer: Brian Michael Bendis; artist: Kris Anka)

(Marvel – writer: Brian Michael Bendis; artist: Kris Anka)

If the day comes that I stop reading X-men comic books, it’ll be because of Scott Summers.

Really, this guy needs to listen to his fellow mutants and shut up and go away for a while. Much of what Summers does is self-serving. Does he really care about his “revolution”? Haven’t a few of the X-men said as much to him already?

In this issue, Summers takes it upon himself to reason with newly-realized mutant Matthew Malloy, despite the protestations of, oh, everyone. Does Summers really think he can get Malloy to join the greater collective of mutants, or is this just another thinly disguised self-flagellation for killing Professor Xavier-slash-revenge on Xavier for keeping secrets from Summers? My vote is for the latter.

And to the rest of the X-men, I ask you collectively: why don’t you ever stop Summers from doing everything you complain about him doing? Wolverine has been itching to do so for a while, but he may or may not be dead at this point. The issue ends with a stall, I mean a cliffhanger, with Magneto stepping up to stop Summers. Magneto’s motivation and timing are questionable as well.

Writer Brian Michael Bendis has shown through the many titles he’s helmed that he plans long-term. I can’t see where things will go with Summers, but something needs to be done to take him down a notch. Summers has a history of one-man pity parties and they get old quick.

Kris Anka steps in on art this issue, despite the cover saying drawings are by the series’ primary artist Chris Bachalo. While Anka and Bachalo have their different styles, their respective tones both work for the book.

I don’t see Uncanny X-men getting out of this stall anytime soon. The title will inevitably have to acknowledge Wolverine’s death, and that could get mired down by showing each of the principal characters’ grief. I’m not ready to bail on Uncanny X-men yet, but holding patterns and circular plotting could tilt me in that direction.